Latest News

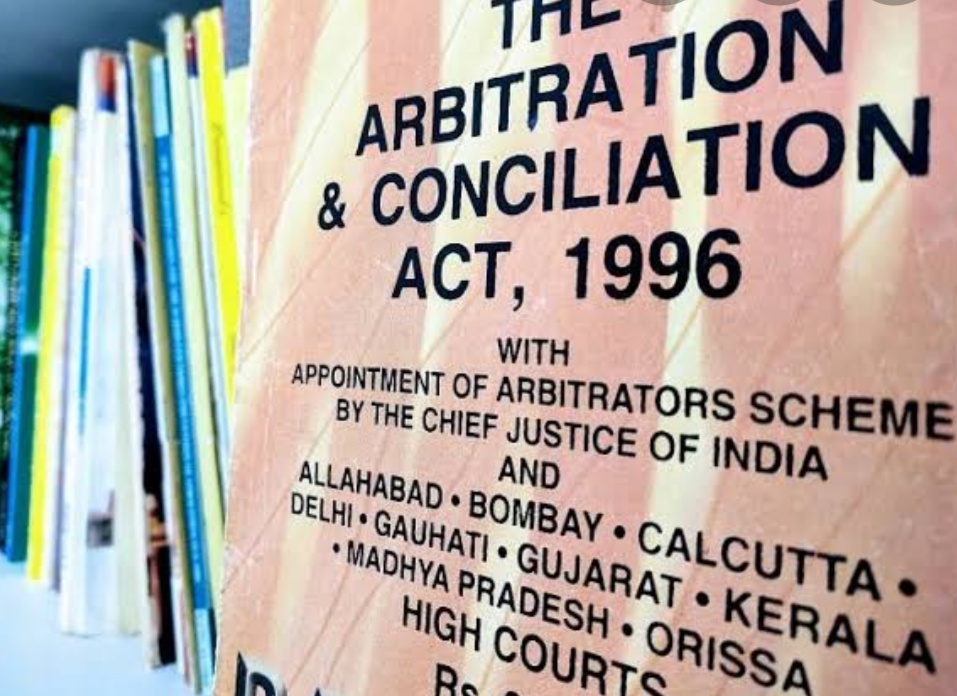

Problems within the arbitration and conciliation act and required changes

Problems within the arbitration and conciliation act and required changes

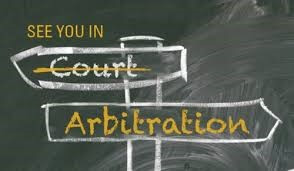

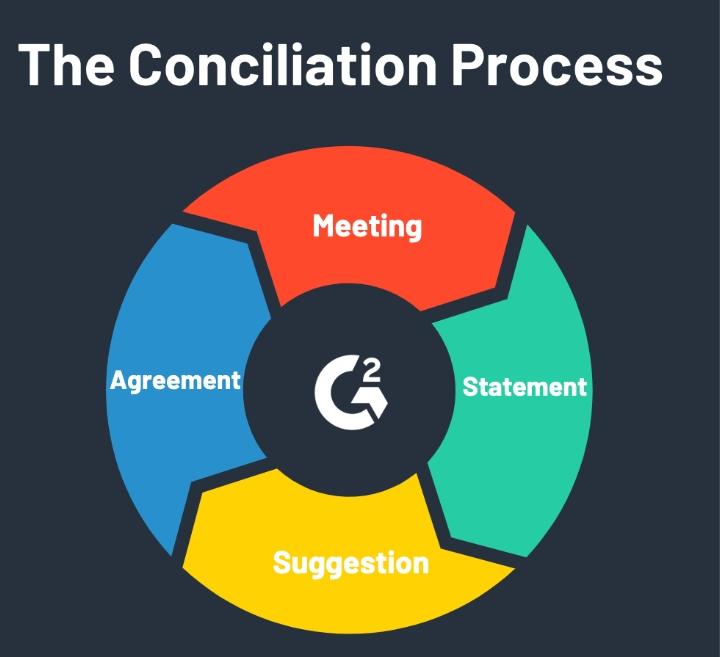

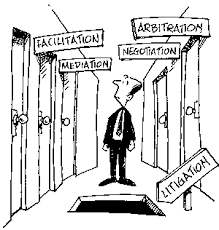

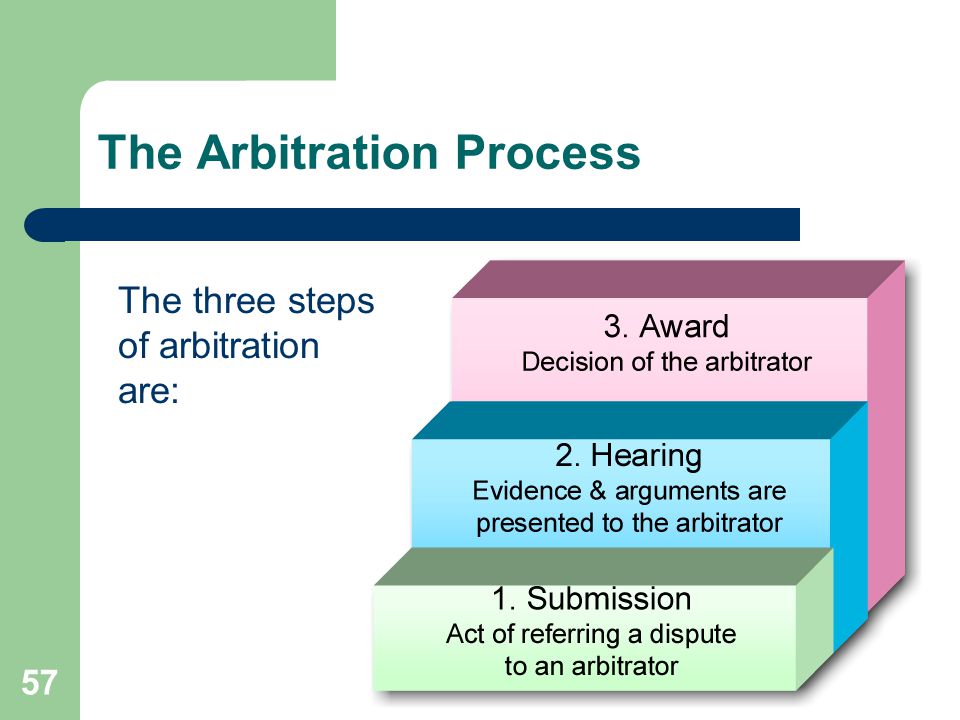

Before the amendment of the Indian Arbitration and Conciliation Act 1996[1] (“the Act”), India’s journey towards becoming a world commercial hub that would rival Singapore and London was hampered by a largely ineffective Act and an arbitration regime that was afflicted with various problems including those of high costs and delays. Although most of the amendments to the Act are welcomed by the arbitration community for their potential in increasing the fairness, speed and economy with which disputes are resolved by arbitration in India, few amendments may end up being counterproductive. The amendments to the Act, though laudable, are only a primary step towards making arbitration the well-liked mode of dispute resolution in India. It must be acknowledged that increased efficiency in arbitration is unlikely to return solely from the imposition of top-down legislative change. A change within the very culture of Indian arbitration is required.

Suggested changes-

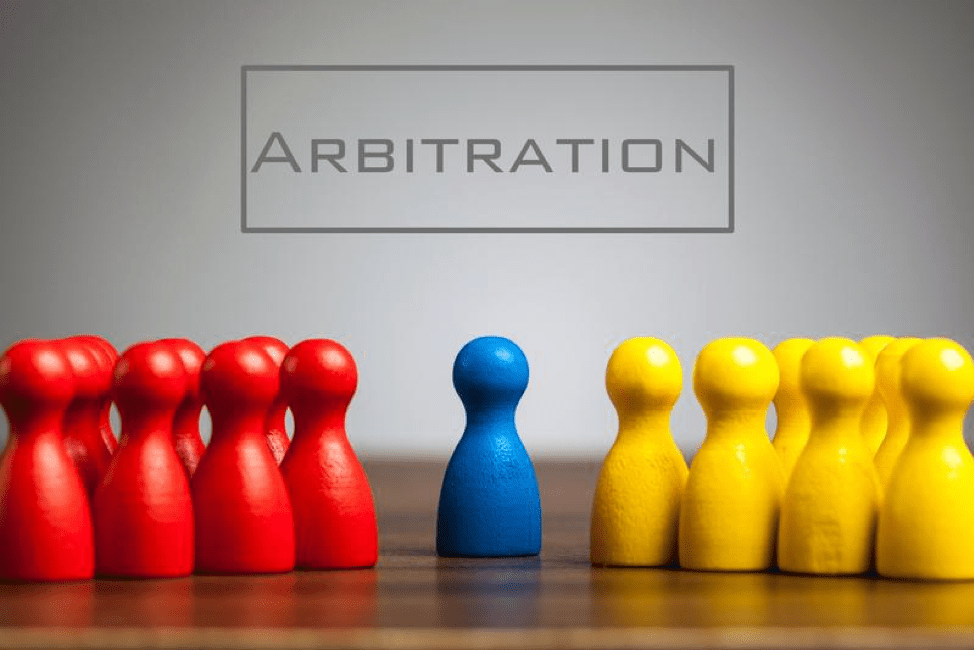

- There must be a change within the perspective with which arbitration is viewed. The pool of Indian legal practitioners who specialised in arbitration has grown and changed the mindset with which arbitration is considered the priority instead of playing second fiddle to Indian court litigation work.

- The arbitrators must grow. Unfortunately, the tendency to appoint retired Indian judges as arbitrators is also stifling arbitration's expansion as a dispute resolution mechanism in India. What is needed is that the growth of a community of arbitrators unfettered by the traditions of the Indian courts and focus on growing arbitration in its claim.

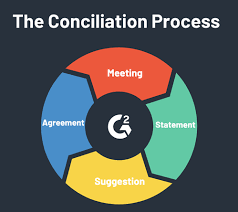

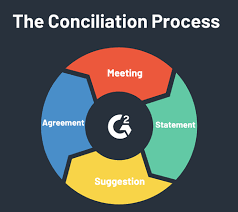

- To proceed towards an arbitration-friendly society, the court must identify the scope of resolution or settlement. Therefore, the same should also be acceptable and recommended to the parties involved.

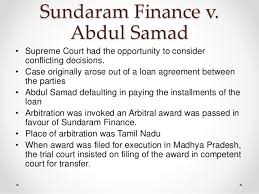

- The final and most vital change needed is that the minimisation of judicial interference. The case of ONGC v Saw Pipes[2] has demonstrated how judicial interference within the arbitration process can take root when there is even the slightest ambiguity in arbitration law, with the interference being of such magnitude that legislative change is essential to remedy it. Unfortunately, even the recent amendments to the Act are riddled with many such ambiguities, thereby providing the chance for further judicial interference.

In conclusion, it is only if the Indian arbitration culture has changed. These persisting problems have been addressed that arbitration will finally become the well-liked mode of dispute resolution in India.

[1] https://legislative.gov.in/sites/default/files/A1996-26.pdf

[2] AIR 2003 SC 2629

This Article Does Not Intend To Hurt The Sentiments Of Any Individual Community, Sect, or Religion, Etcetera. This Article Is Based Purely On The Authors Personal Views And Opinions In The Exercise Of The Fundamental Right Guaranteed Under Article 19(1)(A) And Other Related Laws Being Force In India, For The Time Being. Further, despite all efforts made to ensure the accuracy and correctness of the information published, White Code VIA Mediation and Arbitration Centre Foundation shall not be responsible for any errors caused due to human error or otherwise.

- The amendments to the Act, though laudable, are only a primary step towards making arbitration the well-liked mode of dispute resolution in India.

- There must be a change within the perspective with which arbitration is viewed.

- Judicial intervention should be minimised and so should be the the tendency of appointment of retired judges as arbitrators