Back

Latest News

Bgs Sgs Soma Jv vs Nhpc Ltd.(2019)

BGS SGS Soma JV vs. NHPC Ltd. [2019 SCC Online SC 1585] –

ISSUES BEFORE THE SUPREME COURT

The Supreme Court needed to think about the accompanying issues: (a) Whether the appeal before the High Court under Section 37 of the Arbitration Act was maintainable?; (b) Whether the assignment of a "seat" is similar to a selective jurisdiction provision?; and (c) What is the test to decide the "seat" of arbitration?

JUDGMENT OF THE SUPREME COURT

a) Maintainability of Section 37 Appeal before the High Court:

The High Court had held that it has jurisdiction to hear the appeal as the Commercial Court's structure that the test request is gotten back to court in New Delhi adds up to a request "refusing to set aside an arbitral award under section 34". The Supreme Court alluded to before judgments6 and repeated that Section 377 of the Arbitration Act clarifies that appeals will lie just pursuant to the grounds gave in sub-clauses 1(a) – (c) and from no others. Further, the Supreme Court saw that the request for the Commercial Court didn't identify with a refusal to set aside an arbitral award, and just given that that the Commercial Court doesn't have jurisdiction to hear the challenge to the Award. Thinking about every one of these factors, the Supreme Court held that the appeal recorded before the High Court was not maintainable.

b) The Juridical Seat of Arbitration Proceedings:

The High Court, while alluding to the Supreme Court's choices in BALCO and Indus Mobile Distribution Private Limited v. Datawind Innovations Private Limited and Ors.,8 ("Indus Mobile") saw that the arbitration provision in the current case just alludes to the venue of arbitration proceedings and not the seat of arbitration. On this premise, the High Court held that since an aspect of the reason for action emerged in Faridabad, and then Faridabad Commercial Court was moved toward first, the Faridabad courts alone would have jurisdiction over the arbitral proceedings. The Supreme Court held that a perusing of paragraphs 75, 76, 96, 110, 116, 123 and 194 of BALCO shows that when parties have chosen the seat of arbitration, such a selection would give a restrictive jurisdiction proviso to the courts at the seat of arbitration for the reasons for between time requests and difficulties to Award.

Applying this principle, the Supreme Court inferred that:

-

If the clashing bit of BALCO is kept aside, the very fact that parties have picked a seat would essentially mean that the courts at the seat have selective jurisdiction over the whole arbitral cycle.

-

The proportion in BALCO doesn't indisputably hold that two courts have simultaneous jurisdiction. This is inaccurate as the subsequent paragraphs of BALCO plainly and obviously express that picking a seat adds up to picking the restrictive jurisdiction of the courts at which the seat is found.

The Supreme Court saw that Section 42 of the Arbitration Act has been embedded to maintain a strategic distance from clashes in the jurisdiction of courts by putting the administrative jurisdiction over all arbitral proceedings in a single court only. An application must be made to a Court that has the jurisdiction to choose such an application. At the point when a seat has been assigned, the courts at the seat alone would have jurisdiction and all further applications must be made to a similar Court by the activity of Section 42 of the Arbitration Act.

The Supreme Court additionally held that when a seat has not been assigned by the arbitration understanding, and just a helpful venue has been assigned, there might be a few courts where a piece of the reason for action may have emerged. An application for break alleviation before the commencement of arbitration under Section 9 of the Arbitration Act may then be favored in any court where an aspect of the reason for action hosts emerged as the gatherings/arbitral tribunal has not decided the seat yet. In such a case, the most punctual court before which an application has been made would be considered the court having restrictive jurisdiction and all further applications must lie before this court by the righteousness of Section 42 of the Arbitration Act.

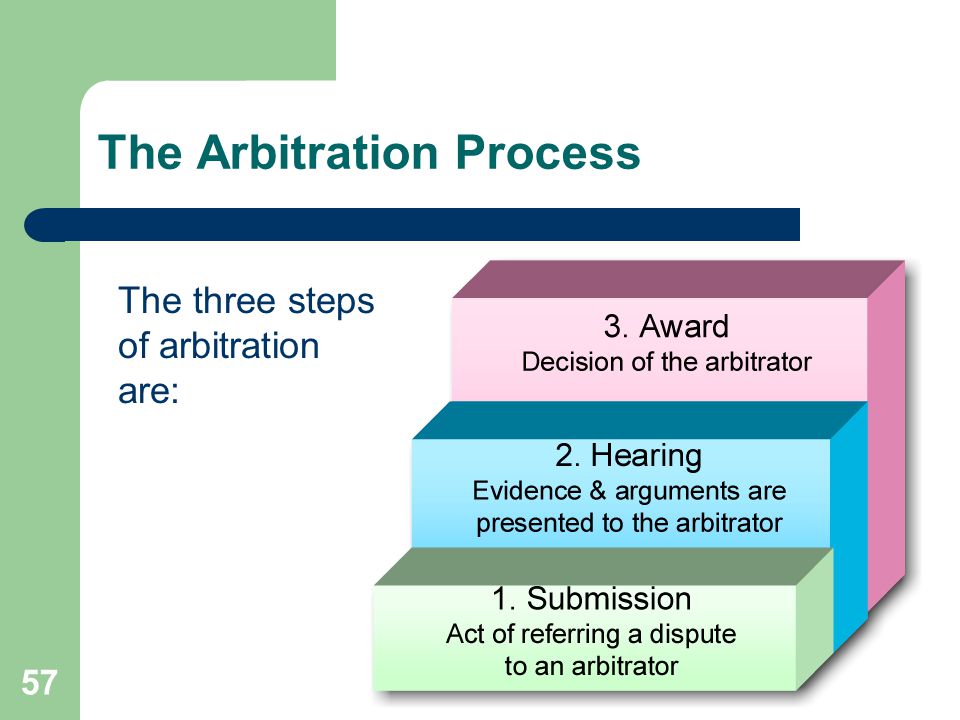

c) Tests for Determination of "Seat"

Depending upon the English Court's choice in Roger Shashoua and Ors. v. Mukesh Sharma, ("Shashoua Principle") the Supreme Court set out that any place there is an express assignment of a "venue", and no assignment of any elective spot as the "seat", joined with a supranational collection of rules administering the arbitration, and no other significant opposite indicia, the inflexible end is that the expressed setting is actually the juridical seat of the arbitral continuing." (accentuation provided)

The Court further held that when there is an assignment of a venue for "arbitration proceedings", the articulation "arbitration proceedings" clarify that the setting ought to be considered the "seat" of arbitration proceedings. Further, the articulation "will be held" at a specific venue would further anchor the arbitral proceedings to a specific place and mean that such spot is the seat of arbitral proceedings.

Unexpectedly, language, for example, tribunals are to meet or have observers, specialists or the parties may mean that such a spot is just the "venue” of the arbitral proceedings. These factors, alongside the fact that there are no other significant opposite indicia to express that the setting is just a venue and not the seat, would show that a venue has for sure been assigned the "seat" of arbitral proceedings.

The Supreme Court held that the three-judge seat in Hardy Exploration11 didn't follow the Shashoua Principle which was affirmed by the Supreme Court in BALCO. Thus, the Supreme Court proclaimed that the law set down in Hardy Exploration isn't acceptable law.

d) Application of the Tests to the Facts of the Case

Upon the facts of the case before it, the Supreme Court noticed that the venue of the arbitration in the arbitration arrangement had been assigned as New Delhi/Faridabad. In any case, as there was no other opposite sign, applying the Shashoua Principle, the Supreme Court held that either New Delhi or Faridabad is the assigned seat under the arbitration understanding. It was therefore dependent upon the parties to pick in which place the arbitration is to be held.

The Supreme Court held that since all the arbitral proceedings were held in New Delhi and the last award was additionally marked in New Delhi, the parties picked New Delhi and not Faridabad as the "seat" of the arbitration under Section 20 of the Arbitration Act. Therefore, the courts at New Delhi would have restrictive jurisdiction over the arbitral proceedings. Regardless of whether some aspect of the reason for action emerged in Faridabad, it is irrelevant as the "seat" hosts been assigned by the gatherings at New Delhi and restrictive jurisdiction vests in the courts of New Delhi. As needs are, the judgment of the High Court was set aside and the Supreme Court requested that the Section 34 appeal be introduced before the courts in New Delhi.

This article does not intend to hurt the sentiments of any individual, community, sect, or religion, etcetera. This article is based purely on the author’s personal opinion and views in the exercise of the Fundamental Rights guaranteed under Article 19(1)(A) and other related laws being enforced in India for the time being.

- Bgs Sgs Soma Jv vs Nhpc Ltd.(2019)

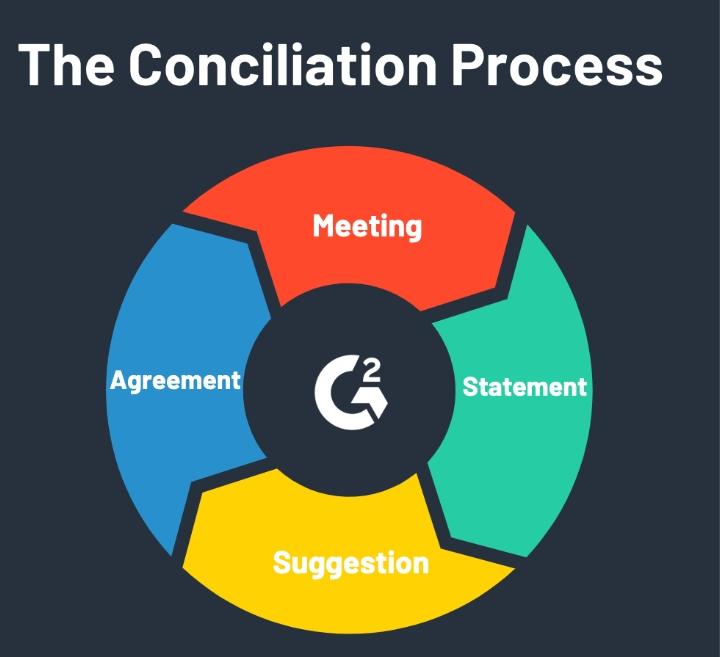

- SECTION 42 OF ARBITRATION AND CONCILIATION ACT

- -