Back

Latest News

India's Pro-Arbitration Stance: Evolving Sovereign Immunity and Enforcement of Arbitral Awards

India's Pro-Arbitration Stance: Evolving Sovereign Immunity and Enforcement of Arbitral Awards

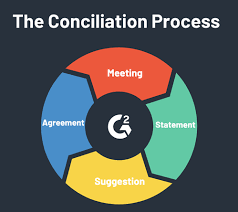

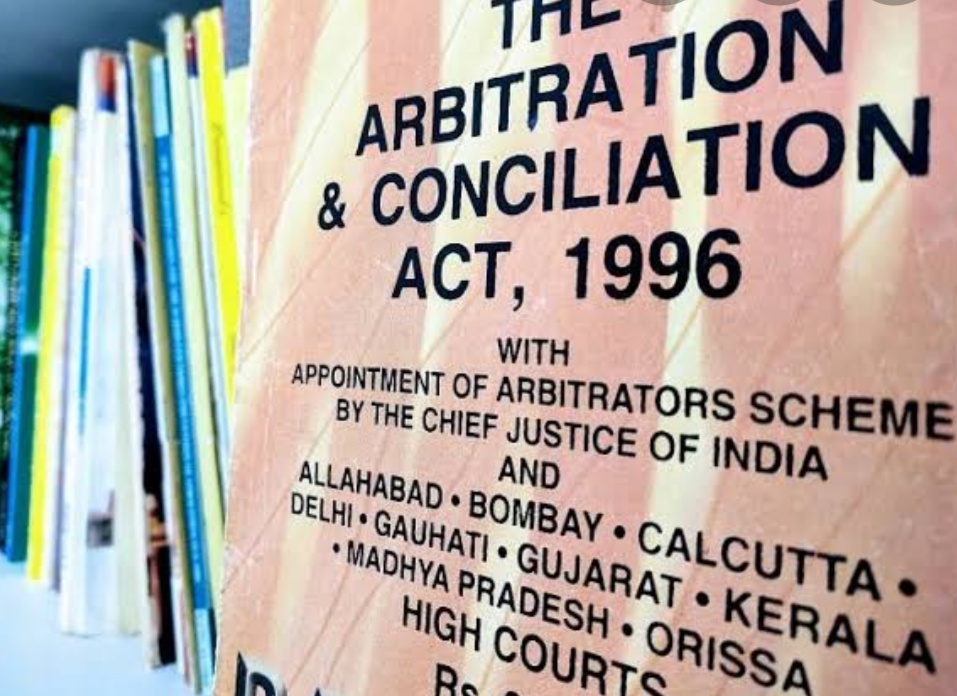

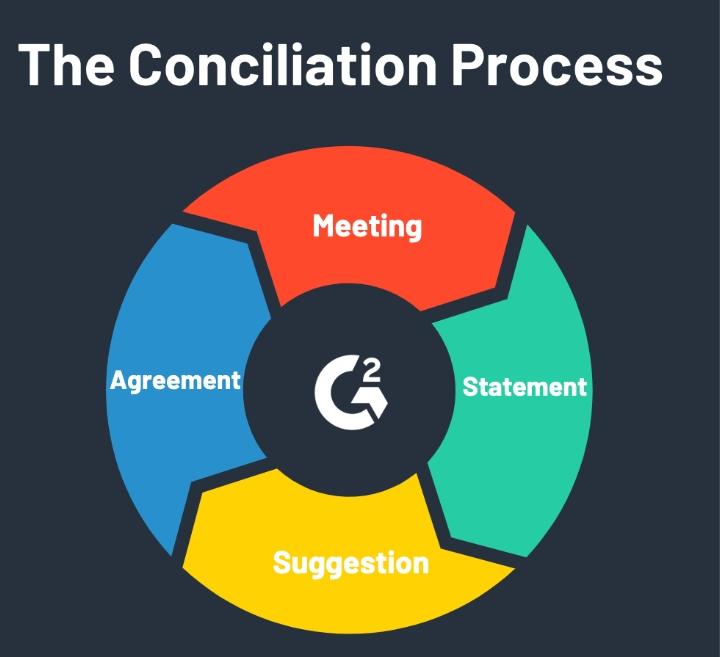

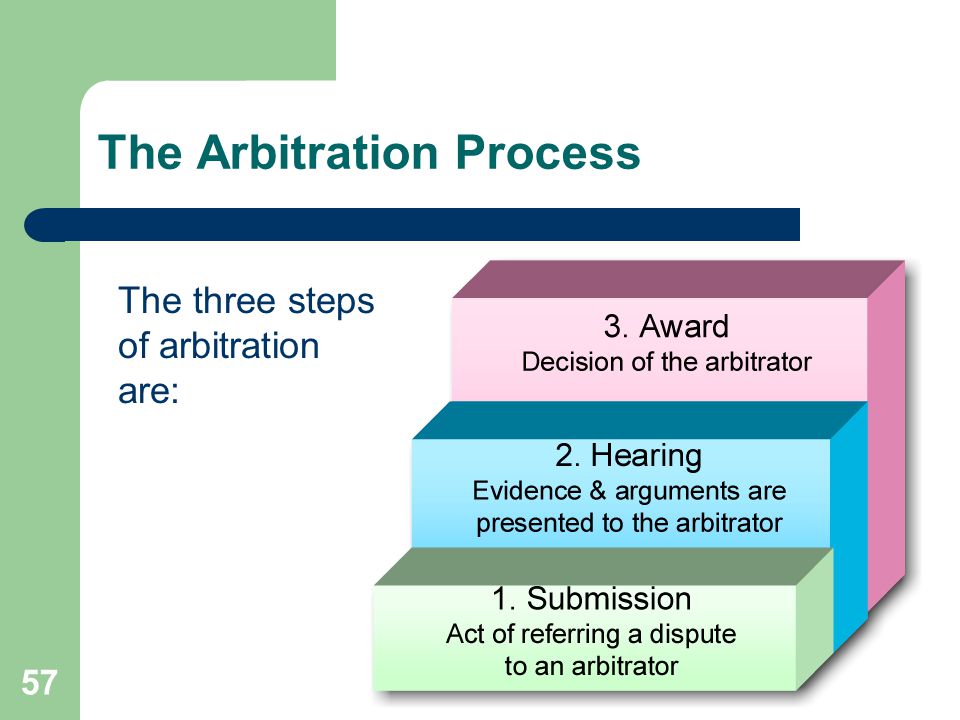

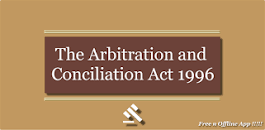

India is emerging as a major pro-business jurisdiction on the international stage, advancing the status quo on sovereign immunity more liberally and practically. The nation has adopted a pro-arbitration stance, as is demonstrated by the 1996 Arbitration and Conciliation Act (ACA) and several court rulings. Nonetheless, the efficacy principle preserves the sacredness of pacta sunt servanda by guaranteeing that the voluntarily agreed agreement to arbitrate is respected and approved when necessary. The ultimate, binding, and immediately enforceable arbitral ruling is essential to the functioning of the international arbitration system. However, the sovereign immunity barrier may make it difficult for the arbitral judgment to be carried out when the award-debtor is a State, particularly if the State refuses to abide by the decision.

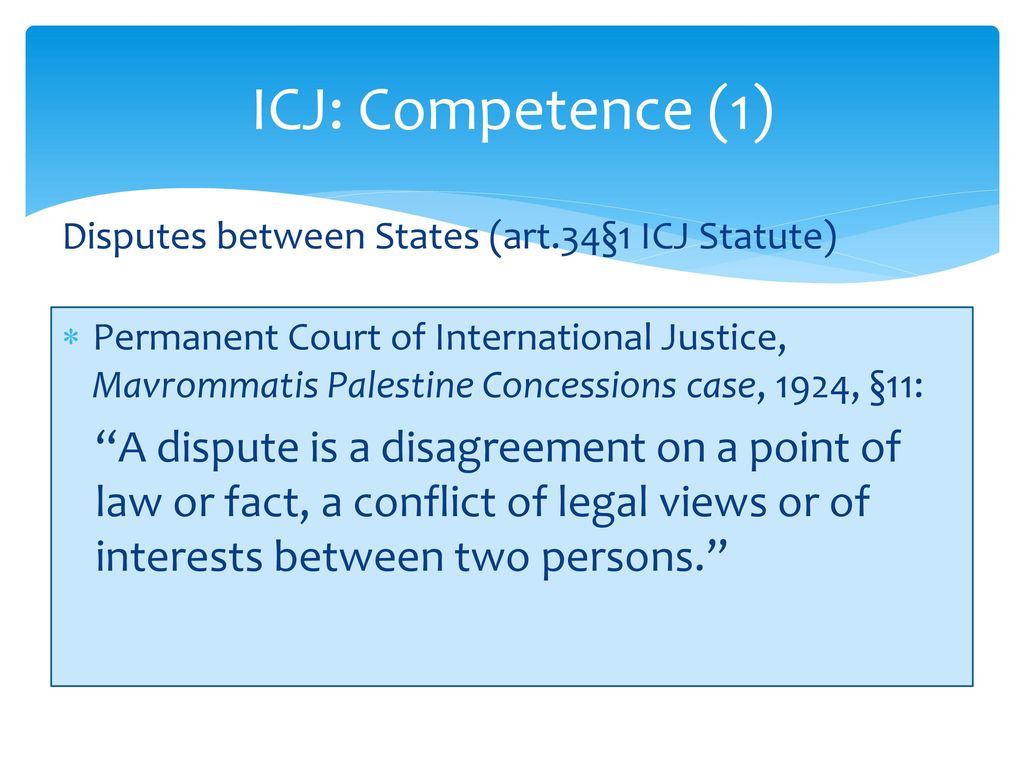

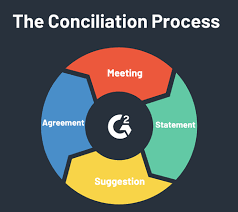

A conceptual shift in civil litigation is necessary to achieve the Code of Civil Procedure's goal of enabling parties to obtain rulings and remedies promptly. The Supreme Court highlights that the means and the purposes of a fair trial in civil action should be the focus of attention. Contrary to popular belief, India has long upheld the limiting notion of immunity, distinguishing between private activities (acta jure gestionis) and sovereign acts (acta jure imperi). Nonetheless, the legislation and forum procedural guidelines govern how sovereign immunity is used. A State's exemption from execution is determined by the purpose rather than the nature test. Given that execution is the last stage of enforcement, this contradiction presents challenges for award creditors in arbitration. By stating a general norm of immunity from adjudication and listing exceptions, the United Nations Convention on Jurisdictional Immunities of States and Their Property (UNCSI) adopts a limited view of immunity.

A foreign state's immunity is defined under the UN Convention on Jurisdictional Immunities of States and Their Property (UNCSI), which covers two different types of immunity: immunity from execution and immunity from jurisdiction. A broad rule of immunity from adjudication and enforcement/execution is adopted by the Convention; nevertheless, it differentiates between the two and makes it more difficult to attach and execute against state property than it is to file a lawsuit against a state. The position of the defendant state in terms of defending against measures of restraint has significantly strengthened, despite considerable liberalization about issues of execution against state assets. Due to the UNCSI's treatment of a significant portion of its provisions as a codification of customary international law, it has garnered positive comments from both domestic and international courts and tribunals, including the ICJ.

Significantly, India's 2007 ratification of the UNCSI shows that the theory of limited sovereign immunity is supported. Approaches of sovereign immunity, and specifically the application of the UNCSI, differ significantly, nevertheless. By international law, Section 86 of the Convention on Civil Procedure (CCP) does not "supplant" sovereign immunity; rather, it adds a new exception to the claim of immunity. Public international law contains information on the reach and application of the sovereign immunity doctrine. The Supreme Court addressed immunity from jurisdiction under Section 86(1) in Ethiopian Airlines v. Saboo. The court cited the ruling in The German Democratic Republic v. The Dynamic Industrial Undertakings Ltd., which found that International Law does not "supplant" the theory of sovereign immunity under Section 86; rather, it establishes "another exception" to immunity. It was appropriate for the Supreme Court to use a comparative legal approach in developing its ruling on sovereign immunity under public international law.

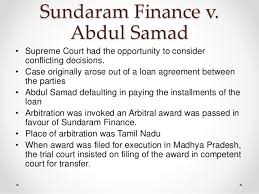

In KLA/Matrix v. Afghanistan/Ethiopia, the court decided that enforcement of arbitral verdicts against a foreign state under Section 86(3) of the Code of Civil Procedure does not require prior approval from the Central Government. The award-debtor states were instructed by the court to deposit the award monies with the Registrar General within four weeks or risk-facing asset attachment. The state cannot invoke sovereign immunity to prevent the implementation of an arbitral ruling resulting from a business transaction, the court further held. The court further determined that a foreign state cannot claim immunity for delaying the implementation of an arbitral ruling because the foreign state views an arbitration clause in a commercial contract as an implicit waiver.

In KLA/Matrix v. Afghanistan/Ethiopia, the Indian Supreme Court upheld the twofold waiver theory, stating that the prior consent requirement from a procedural code is incompatible with contemporary arbitral rulings. The court contended that the term "decree" used to describe an arbitral decision is fictitious and serves only to make the award's treatment final, legally binding, and immediately enforceable. The court further stressed that enforcement of an award in arbitration is equivalent to enforcement of a commercial international arbitral award and that arbitration is a voluntary and binding method of resolving disputes. Due to the court's ruling, India may become the most pro-arbitration nation in the world when it comes to executing arbitral verdicts against governments that award debtors, eliminating the uncertainty that comes with costly and time-consuming litigation.

A conceptual shift in civil litigation is necessary to achieve the Code of Civil Procedure's goal of enabling parties to obtain rulings and remedies promptly. The Supreme Court highlights that the means and the purposes of a fair trial in civil action should be the focus of attention. Contrary to popular belief, India has long upheld the limiting notion of immunity, distinguishing between private activities (acta jure gestionis) and sovereign acts (acta jure imperi). Nonetheless, the legislation and forum procedural guidelines govern how sovereign immunity is used. A State's exemption from execution is determined by the purpose rather than the nature test. Given that execution is the last stage of enforcement, this contradiction presents challenges for award creditors in arbitration. By stating a general norm of immunity from adjudication and listing exceptions, the United Nations Convention on Jurisdictional Immunities of States and Their Property (UNCSI) adopts a limited view of immunity.

A foreign state's immunity is defined under the UN Convention on Jurisdictional Immunities of States and Their Property (UNCSI), which covers two different types of immunity: immunity from execution and immunity from jurisdiction. A broad rule of immunity from adjudication and enforcement/execution is adopted by the Convention; nevertheless, it differentiates between the two and makes it more difficult to attach and execute against state property than it is to file a lawsuit against a state. The position of the defendant state in terms of defending against measures of restraint has significantly strengthened, despite considerable liberalization about issues of execution against state assets. Due to the UNCSI's treatment of a significant portion of its provisions as a codification of customary international law, it has garnered positive comments from both domestic and international courts and tribunals, including the ICJ.

Significantly, India's 2007 ratification of the UNCSI shows that the theory of limited sovereign immunity is supported. Approaches of sovereign immunity, and specifically the application of the UNCSI, differ significantly, nevertheless. By international law, Section 86 of the Convention on Civil Procedure (CCP) does not "supplant" sovereign immunity; rather, it adds a new exception to the claim of immunity. Public international law contains information on the reach and application of the sovereign immunity doctrine. The Supreme Court addressed immunity from jurisdiction under Section 86(1) in Ethiopian Airlines v. Saboo. The court cited the ruling in The German Democratic Republic v. The Dynamic Industrial Undertakings Ltd., which found that International Law does not "supplant" the theory of sovereign immunity under Section 86; rather, it establishes "another exception" to immunity. It was appropriate for the Supreme Court to use a comparative legal approach in developing its ruling on sovereign immunity under public international law.

In KLA/Matrix v. Afghanistan/Ethiopia, the court decided that enforcement of arbitral verdicts against a foreign state under Section 86(3) of the Code of Civil Procedure does not require prior approval from the Central Government. The award-debtor states were instructed by the court to deposit the award monies with the Registrar General within four weeks or risk-facing asset attachment. The state cannot invoke sovereign immunity to prevent the implementation of an arbitral ruling resulting from a business transaction, the court further held. The court further determined that a foreign state cannot claim immunity for delaying the implementation of an arbitral ruling because the foreign state views an arbitration clause in a commercial contract as an implicit waiver.

In KLA/Matrix v. Afghanistan/Ethiopia, the Indian Supreme Court upheld the twofold waiver theory, stating that the prior consent requirement from a procedural code is incompatible with contemporary arbitral rulings. The court contended that the term "decree" used to describe an arbitral decision is fictitious and serves only to make the award's treatment final, legally binding, and immediately enforceable. The court further stressed that enforcement of an award in arbitration is equivalent to enforcement of a commercial international arbitral award and that arbitration is a voluntary and binding method of resolving disputes. Due to the court's ruling, India may become the most pro-arbitration nation in the world when it comes to executing arbitral verdicts against governments that award debtors, eliminating the uncertainty that comes with costly and time-consuming litigation.

- India’s Arbitration and Conciliation Act (1996) and Supreme Court rulings emphasize the enforceability of arbitral awards, even against sovereign states.

- India adheres to the limited notion of sovereign immunity, distinguishing between private and sovereign acts, with the UN Convention on Jurisdictional Immunities of States.

- Indian courts, particularly in KLA/Matrix v. Afghanistan/Ethiopia, ruled that sovereign immunity cannot block enforcement of arbitral awards.