Latest News

Expanding the Scope of Consent: Non-Signatory Involvement in Arbitration Proceedings

Introduction

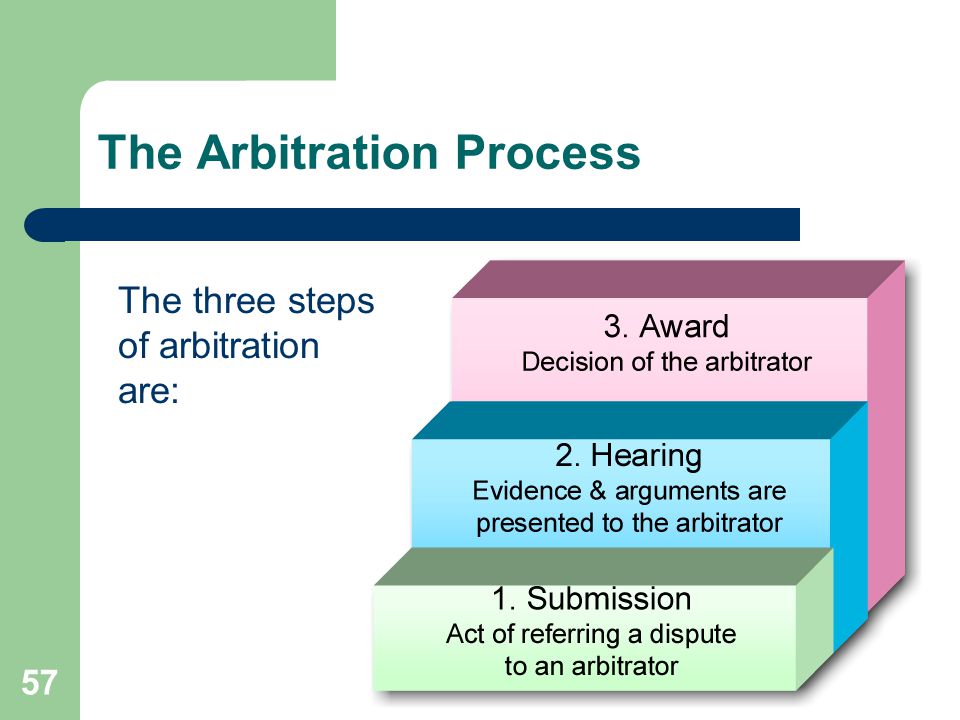

Arbitration is a procedure where parties to a contract agree to subject their disputes to a panel of arbitrators to decide on them. It is an alternative method to litigation, not a substitute. This, in itself, highlights the importance of consent in arbitration. The consensus holds that arbitration is consensual, not coercive and “no one can be forced to arbitrate absent of an agreement to do so”[1]. Compelling an entity that did not undertake to arbitrate goes against the very roots of arbitration. Even the New York Convention[2] recognizes that an agreement only binds those parties that are signatories to it and grants them the right to invoke the jurisdiction of a competent court in the event of any breach.

However, there are times when an entity that is not a signatory to an arbitration agreement is brought up in the arbitration proceedings which requires extending the arbitration clause by imposing an obligation beyond the circle of the parties who agreed to arbitrate. In such situations, tribunals and courts look more to the implied nature of consent wherein unsigned commitments to arbitrate are recognized.

Can a third-party non-signatory to the arbitration agreement be compelled to arbitrate? This article delves into the various grounds upon which such liability can be determined to the extent that the third party in question has taken part in the performance of the contract containing the arbitration clause.

General Considerations

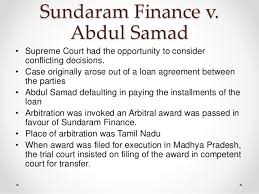

The permissibility of binding third-party non-signatories to an arbitration agreement depends largely upon the jurisdiction subject to which the proceedings are being held. While some national jurisdictions permit the act of binding non-signatories to a contract by applying their legal doctrines, International arbitral tribunals are tasked with determining the conflict of laws applicable to the matter before them. They may refer to national laws or they may choose to adopt broader principles including but not limited to lex mercatoria, bona fides, or agreement of the parties. The former makes the determination of the matter much more predictable, whereas, the latter route entails some amount of unpredictability for transnational entities.

In addition to the above, the issue of adding parties to proceedings is a matter of jurisdiction, not substance, and the Model Law[3] vests within the arbitral tribunals the power to decide matters according to their jurisdiction. That is to say, determination should refer to the lex loci arbitri or the rules of the institution. In one case, the International Chamber of Commerce tribunal noted that “the parties having adopted ICC rules, the tribunal held the authority to decide, as to its jurisdiction, ‘which provisions do not refer to the application of any national law.”[4]

In a more recent ruling, the High Court at New Delhi, India, determined that since the arbitration agreement subjected arbitration to the Singapore International Centre of

Arbitration (SIAC) the issue of binding the non-signatory party should be determined about the SIAC rules (2016) accordingly[5].

There exists an array of methods, theories and doctrines that have been accepted as appropriate and applicable law (although some in part only) when determining whether a particular third-party non-signatory to the arbitration agreement can be compelled to arbitrate.

Methods of Extending the Scope of an Arbitration Agreement

- Group of Companies Doctrines:

This doctrine was first introduced in the Dow Chemical[6] case. It provides that several companies that form a part of a larger corporate group may be regarded as a single legal entity or ‘une réalité économique unique’[7]. In essence, this doctrine assumes the joint liability of the affiliate group. They may benefit from or be bound by an arbitration agreement entered into by any one of them.[8]

Dow Chemical v. Isover Saint Gobain ICC No. 4131/ 1982:

- Considered the parent case of the ‘group of companies’ doctrine, this landmark decision observed the parent company’s liability towards an agreement applicable to its subsidiaries, stating that:

“Considering that it is indisputable, and not disputed, that Dow Chemical Company USA) has and exercised absolute control over its subsidiaries having either signed the relevant contracts or, like Dow Chemical (France), effectively and individually participated in their conclusion, their performance and their termination.”[9]

- In this case, several subsidiaries of Dow Chemical (USA) had entered into contracts (containing arbitration clauses) with Isover Saint Gobain to which Dow Chemical (USA) was not a signatory. When a dispute arose between the subsidiary parties and Isover, Dow Company (USA) sought to join the arbitral proceedings. Isover strongly objected to this joinder arguing that Dow Company (USA) was not a party to the arbitration agreement, therefore it could not be a party to the arbitral proceedings.

- The Tribunal used the ‘group of companies’ doctrine and added Dow Chemical (USA) as a party to the proceedings according to the ICC rules.

Scope:

- The doctrine does not have a boundless application, as it was held in ICC award No. 6519/ 1991[10] that: “Only those companies of the group that played a part in the negotiation, conclusion, or termination of the contract may find themselves bound by the arbitration clause, which, at the time of the signature of the contract, virtually bound the economic entity constituted by the group. Beyond the General principle, the arbitration should thus appreciate, on a case-by-case basis, not only the existence of an intention of the members of the group to bind it as a whole but also, especially, if such intent is established, its practical effects vis-á-vis each of the companies of the group considered separately.”

- The doctrine considers implied consent by control, participation and affiliation.

- Consensus dictates that corporate independence cannot be disregarded on mere membership in a group and to extend liability “the signatory must have behaved in a manner from which it can be inferred that it has accepted to submit to the arbitration agreement.”[11]

- Estoppel:

This principle holds that a party that has not necessarily agreed to arbitration may be compelled to arbitrate in any proceeding that may result from an arbitration agreement.

The provisions under estoppel are widely recognized to the point that they may be considered lex mercatoria[12], however, it appears as though only American Courts have made use of the doctrine to extend the scope of an arbitration clause to a non-signatory[13].

In the International Paper Company case[14], it was observed as follows: “Equitable estoppel precludes a party from asserting rights he otherwise would have had against another when his conduct renders the assertion of those rights contrary to equity. In the arbitration context…a party may be estopped from asserting that the lack of his signature on the written contract precludes enforcement of the contract when he has consistently maintained that other provisions of the same contract should be enforced to benefit him.”

The following are the grounds upon which estoppel may be used to compel a third-party non-signatory to arbitrate:

Direct Benefit;

A party cannot escape liability on the mere factum of not being a signatory when it receives a direct benefit from the agreement containing the arbitration clause[15].

That is to say, if a party is benefitting from an agreement with an arbitration clause, they may equitably be estopped from refusing to arbitrate as their conduct implies acceptance of an obligation under the same[16].

Direct benefit can mean “reliance on a contract as grounds for litigation”[17] or even “significantly lower insurance rates and the ability to sail under the French flag”[18].

Two-Pronged Estoppel Test;[19]

Also referred to as the Heckler Test[20], the two-pronged estoppel test compels a third-party non-signatory to arbitrate when:

- Their claims rely on or presume the existence of a contract containing an arbitration provision[21].

- Their claims allege concerted misconduct[22].

Where both conditions have been fulfilled, the party in question may be compelled to join the arbitration proceedings, however, should any one of them be in the negative, this principle will not apply.

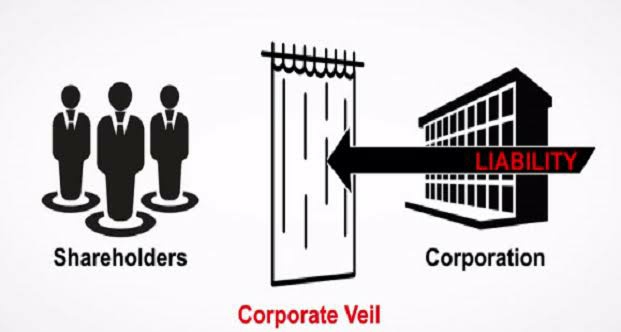

- Alter-Ego Doctrine:

Popularly known as piercing the corporate veil, this principle binds a corporation to an agreement entered into by its shareholders without regard to the structure of the agreement or the shareholder’s attempts to bind itself alone to its terms. To put it simply, the piercing of the corporate veil occurs where the conduct of the third party and its shareholder demonstrates a virtual abandonment of separateness.[23]

This doctrine may be applied where:

- The third party has complete dominance of the signatory

- The corporate form has been used to achieve fraud

- Such fraud has caused injury to the party claiming against them.[24]

By applying this doctrine, the independence of a corporation is disregarded and its owners are held liable, in tandem, for the corporation's obligations. However, the court also considers whether it would be unfair to the corporation or the claimant if the owners are protected from personal liability.

- Agency:

As the general principles of agency provide, the principal shall become vicariously liable and bound by arbitration agreements entered into by his agent(s) if he is a disclosed principal. Where the principal is undisclosed but his conduct implies and leads a third party to believe that the agency has the authority to act on his behalf, he cannot escape liability even when the agent acts without his authority.[25]

Conclusion

The indisputable fact remains that arbitration is consent-centric and seeking to compel parties that have not accepted the undertaking of any such obligation may seem counter-intuitive, improper and unfounded. However, expanding the scope of consent in arbitration to include non-signatories has proven to be essential in certain situations such as parties denying liability to an agreement from which they are deriving benefits simply because they are not signatories. It allows for a more comprehensive and fair resolution of disputes by ensuring that all perspectives are taken into account.

References

[1] InterGen v. Grina, 344 F.3d 134 (1st Cir. 2003)

[2] United Nations Convention on the Recognition and Enforcement of Foreign Arbitral Awards, New York, June 10, 1958, 575 U.N.T.S. p159 (The New York Convention), Article 11

[3] The UNCITRAL Model Law on International Commercial Arbitration, Article 16(1)

[4] ICC Tribunal in Dow Chemical Company v. Isover Saint Gobain, ICC No.4131/ 1982

[5] Tomorrow Sales Agency v. SBS Holdings Private Ltd, FAO (OS) (Comm)59/ 2023

[6] Dow Chemical, Op Cit

[7] See Simon Brinsmead: ‘Extending the Application of an Arbitration Clause to Third-Party Non-Signatories: ‘Which law should Apply?’

[8] Mohit Saraf and Luthra & Luthra: ‘Who is a Party to an Arbitration Agreement – Case of Non-Signatory,’ Institutional Arbitration in Asia (2007)

[9] Dow Chemical, Op Cit. at 132-33

[10] ICC Award No.6519/ 1991, 118 Journal du Droit International 1065

[11] Poudret and Besson p229; Tang Edward Ho Ming, ‘Methods to extend the Scope of an Arbitration Agreement to Third-Party Non-Signatories’

[12] James M. Hosking, ‘Third-Party Non-Signatory’s Ability to Compel International Commercial Arbitration: ‘Doing Justice without destroying Consent,’ Pepperdine Dispute Resolution Law Journal, Vol 4

[13] Simon Brinsmead, Op Cit. at p10, ‘Estoppel’

[14] International Paper Company v. Schwabedisen Maschinen and Anlagen GMBH 206 F 3d

[15] American Bankers Insurance Group v. Long, 453 F 3d (2006), p623: Hanotian p105

[16] Meyer v. WMCO-GP L.L.C, 211 S.W. 3d 302, 305 (Texas SC 2006)

[17] Redfern and Hunter, p418

[18] America Bureau of Shipping v. Tencara Shipyard S.P.A, 170 F. 3d 349 (1999)

[19] Grigson v. Creative Artists 250 F.3d 524 (5th Cir. 2000)

[20] Heckler v. Community Health Services, 467 U.S 56 (1984)

[21] Sunkist Soft Drinks Inc. v. Sunkist Growers Inc. 10 F. 3d 757 (11th Cir. 1993)

[22] MS Dealer Service Corp. v. Franklin 177 F. 3d 942 (4th Cir. 1999)

[23] Tang E. Ho Ming, Op Cit at p24

[24] W.M Passalacqua Builders v. Resnick Developers, 933 F.2d 131 (2nd Circ. 1991)

[25] Article 15, Convention on Agency in the International Sales of Goods

- arbitration is consensual, not coercive and “no one can be forced to arbitrate absent of an agreement to do so”

- A party cannot escape liability on the mere factum of not being a signatory when it receives a direct benefit from the agreement containing the arbitration clause

- expanding the scope of consent in arbitration to include non-signatories has proven to be essential in certain situations.