Latest News

Arbitration Odyssey: India's Potential in Light of the 2024 Arbitration Act 1996 Reforms (UK)

Introduction

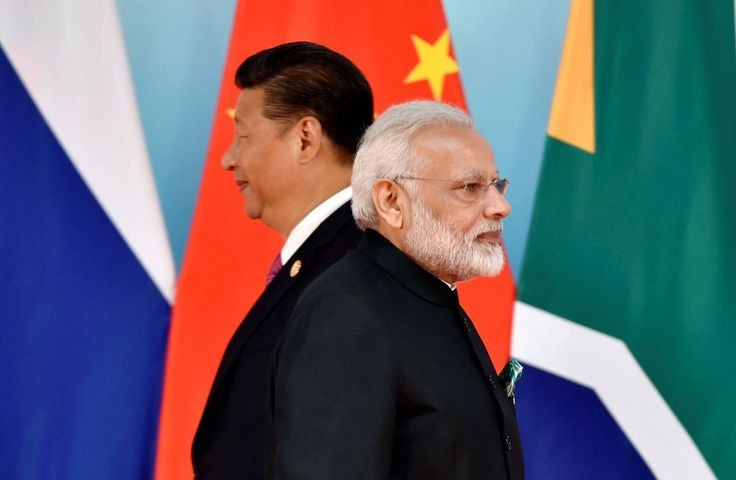

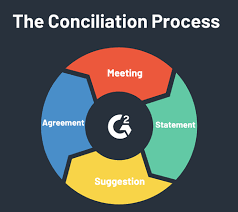

In international arbitration, several jurisdictions strive to create an ambient environment for parties, transnational or otherwise, seeking to settle their disputes. The UK has set itself apart with its pragmatic arbitration practices securing its seat as a global arbitration hub. India on the other hand, is a growing arbitration seat with its eyes set on becoming a global arbitration hotspot. The UK recently affirmed its intention to reform the Arbitration Act 1996 to maintain and enhance its reputation. As an aspiring global arbitration hub, how does Indian arbitration fare when brought up against the recommended reforms in the UK? This article explores this question with a comparative view of the UK reforms and the existing arbitration rules in India.

Confidentiality:

UK Reform:

- The English reforms emphasise the importance of confidentiality and maintain the flexibility for parties to agree on confidentiality terms. The absence of a statutory rule reflects a preference for case law and arbitral practices.

Indian Law:

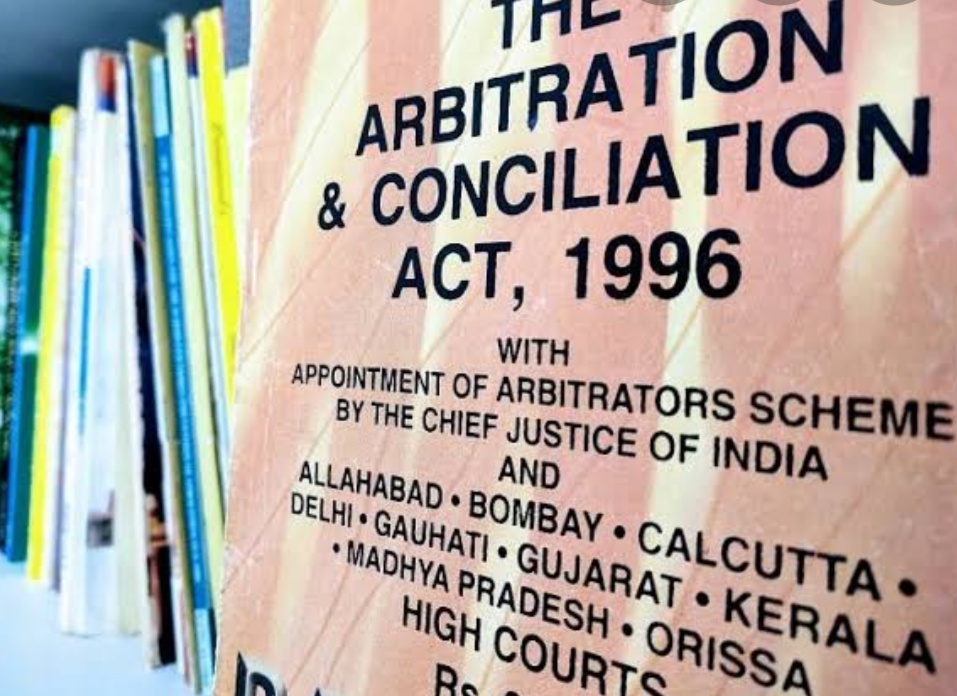

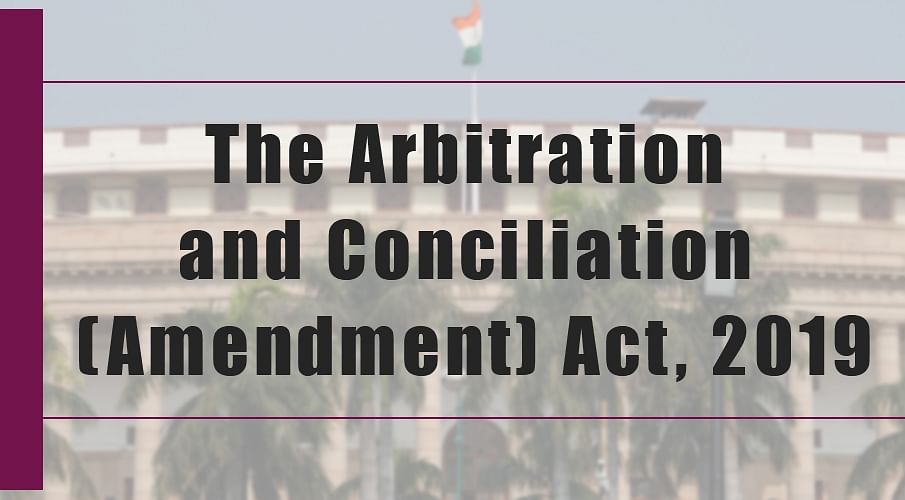

- Indian arbitration laws, particularly the Arbitration and Conciliation Act 1996, recognise and emphasise the confidentiality of arbitral proceedings. The Amendment Act of 2019 introduced Section 42-A as a provision on confidentiality.

Arbitrator Independence, Disclosure, Removal, and Resignation:

UK Reform:

- England's emphasis on maintaining the arbitrator's impartiality without imposing a statutory duty of independence aligns with a pragmatic approach.

Indian Law:

- Indian arbitration law also underscores the importance of arbitrator impartiality and independence. Sections 12 and 18 of the Arbitration Act of 1996 mandate the disclosure of any circumstances affecting an arbitrator's independence. Removal procedures are outlined in Section 14.

Challenging Arbitral Awards: Substantive Jurisdiction

UK Reform:

- Proposes that the court should not entertain new grounds of objection or new evidence in a section 67 challenge unless it couldn't have been presented before the tribunal.

- Recommends avoiding a full rehearing, with the court considering the tribunal's ruling in the interests of justice.

- Recommends implementing changes through court rules rather than legislative amendments.

- The reforms in England focused on refining the procedures for challenging arbitral awards, particularly related to substantive jurisdiction under Section 67 of the Arbitration Act, of 1996.

Indian Law:

- Indian arbitration laws, under Section 34 of the Arbitration and Conciliation Act allow challenges to arbitral awards on limited grounds, including jurisdiction.

- However, the scope and procedure differ, India does not explicitly address the concept of competence-competence as extensively and the Act does not explicitly limit new grounds or evidence during a court challenge.

Governing Law of Arbitration Agreements:

UK Reform:

- Recommends adding a new rule to the Arbitration Act 1996, stating that the law governing the arbitration agreement is either the law expressly agreed upon by the parties or, in the absence of such agreement, the law of the seat of arbitration.

- Proposes that an agreement on the governing law of the matrix contract does not constitute an express agreement for the arbitration agreement.

- The proposed default rule in England concerning the governing law of arbitration agreements aims to simplify complexities, offering a balanced approach between party autonomy and legal clarity.

Indian Law:

- Indian arbitration law does not prescribe specific rules regarding the governing law of arbitration agreements. It typically follows the law chosen by the parties or the law of the seat.

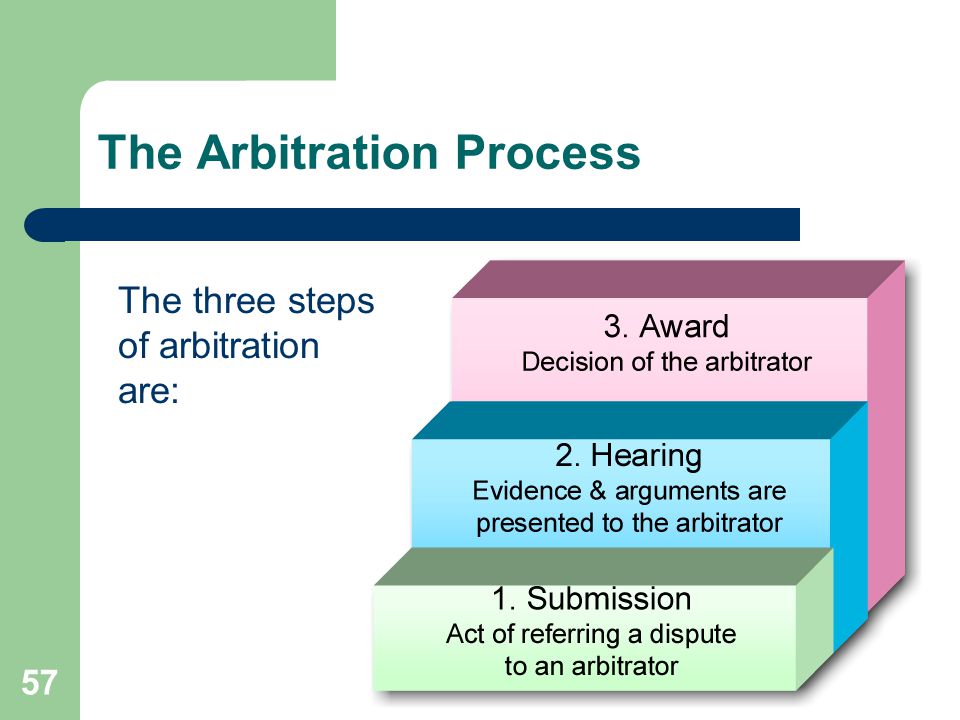

Summary Disposal in Arbitration Proceedings:

UK Reform:

- Proposes allowing arbitral tribunals, with party agreement, to issue awards on a summary basis.

- Recommends the tribunal, after consulting parties, to adopt a suitable procedure for summary disposal.

- Suggests "no real prospect of success" as the threshold for summary disposal, with parties free to agree on a different threshold.

Indian Law:

- Indian law lacks explicit provisions for summary disposal in arbitration proceedings.

- The Arbitration and Conciliation Act 1996, doesn't specifically address the procedure for summary disposal.

Court Powers in Support of Arbitral Proceedings:

UK Reform:

- Recommends amending section 44 to confirm that orders can be made against third parties.

- Proposes that the restricted right of appeal under section 44(7) should not apply to third parties, allowing them usual appeal rights.

Indian Law:

- The Arbitration and Conciliation Act 1996 grants the courts broad powers to support arbitral proceedings (Section 9).

- However, the Act does not explicitly address whether court orders can be directed at third parties.

Emergency Arbitrators:

UK Reform:

- Recommends not introducing a court-administered scheme for emergency arbitrators.

- Proposes that the Act should not apply generally to emergency arbitrators, and their regulation should be through agreed rules of administration.

- Suggests court enforcement of emergency arbitrator orders under section 44.

Indian Law:

- The Arbitration and Conciliation Act 1996, does not specifically address emergency arbitrators.

- The Act only empowers courts to grant interim measures in support of arbitration (Section 9).

Appeal on a Point of Law:

UK Reform:

- It does not recommend any reform to section 69, maintaining the status quo (A party to an arbitral proceeding may appeal to the court on a question of law).

Indian Law:

- Section 37 of the Arbitration and Conciliation Act allows an appeal to the court on a point of law.

Costs:

UK Reforms:

- Recommends amending the Arbitration Act 1996 to state explicitly that an arbitral tribunal can award costs in consequence of a ruling that it has no substantive jurisdiction.

Indian Law:

- Section 31(8) of the Arbitration and Conciliation Act, 1996, empowers the tribunal to award costs.

Conclusion

UK: The proposed reforms exhibit a nuanced and flexible approach with a focus on preserving the strengths of the existing system while addressing specific areas for improvement.

India: India's arbitration framework has undergone significant changes, aligning with international best practices. The emphasis on confidentiality, impartiality, and procedural efficiency is shared between the two jurisdictions.

While both jurisdictions share common principles rooted in international arbitration practices, the specific legal provisions and procedures demonstrate unique approaches tailored to their legal frameworks and historical developments. The UK reforms propose specific amendments to enhance efficiency and clarity, whereas, Indian arbitration law provides a broader framework with inherent flexibility. Both jurisdictions aim to balance party autonomy, procedural fairness, and enforceability of arbitral awards.

- In international arbitration, several jurisdictions strive to create an ambient environment for parties, transnational or otherwise, seeking to settle their disputes.

- The English reforms emphasise the importance of confidentiality and maintain the flexibility for parties to agree on confidentiality terms.

- Both jurisdictions share common principles rooted in international arbitration practices.