Latest News

Tata Sons Private Limited Vs Siva Industries And Holding Limited: Case Analysis

Tata Sons Private Limited Vs Siva Industries And Holding Limited: Case Analysis

Facts of the Case

The Applicant, the first Respondent, and Tata Tele Services Ltd (hereinafter “TTSL”) agreed to issue shares of Tata Tele Services Ltd to the first Respondent in a share subscription agreement dated February 24, 2006. The first Respondent's guarantee is provided by the second Respondent. A little while later, TTSL, the applicant, and the Japanese company NTT Docomo Inc. entered into a share subscription arrangement. Through the use of both primary and secondary shares, Docomo attempted to obtain a 26% ownership investment in TTSL. The first respondent gave Docomo equity shares, and the two sides legally recorded the terms and conditions of their arrangement in a Shareholders' Agreement. In addition, a mutually agreed-upon Inter se agreement was signed, requiring the respondents to purchase Tata Tele Services Ltd. shares in a proportionate amount if Docomo decided to exercise its option to sell.

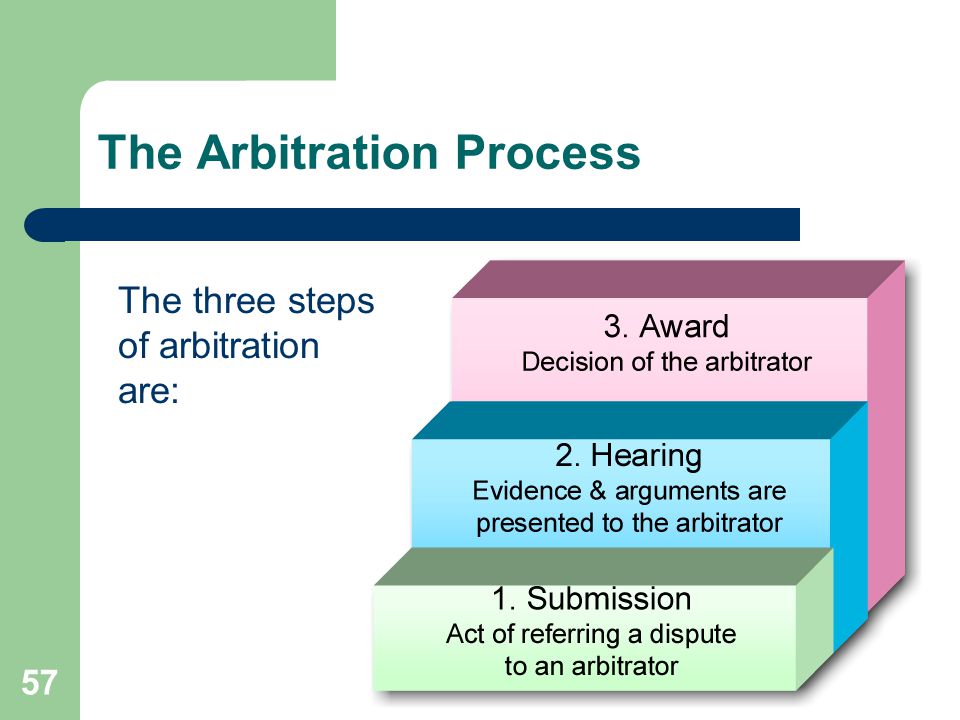

Docomo executed its selling option in July 2014 and notified the applicant of the transaction. A dispute arose between the two parties, and arbitration was subsequently initiated. The applicant was required to buy the TTSL shares and pay Docomo the damages after the Tribunal ruled in Docomo's favour.

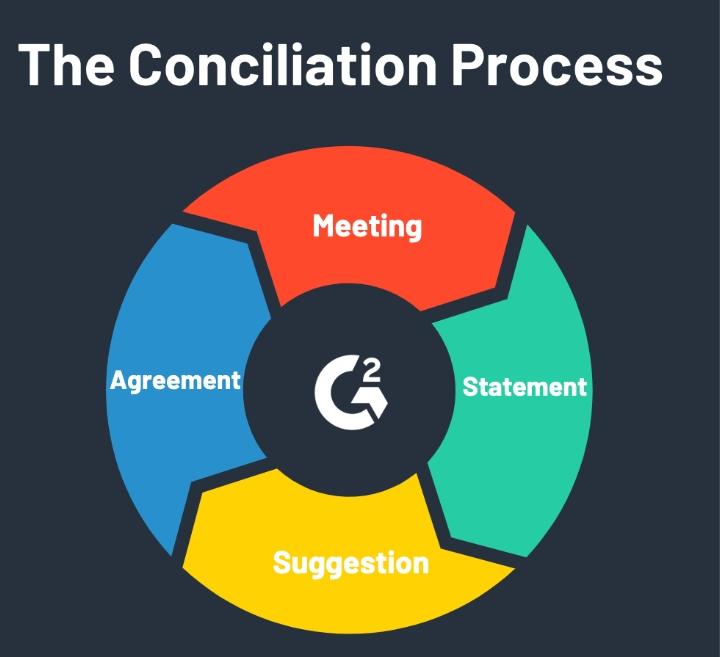

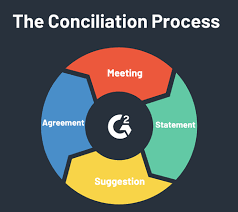

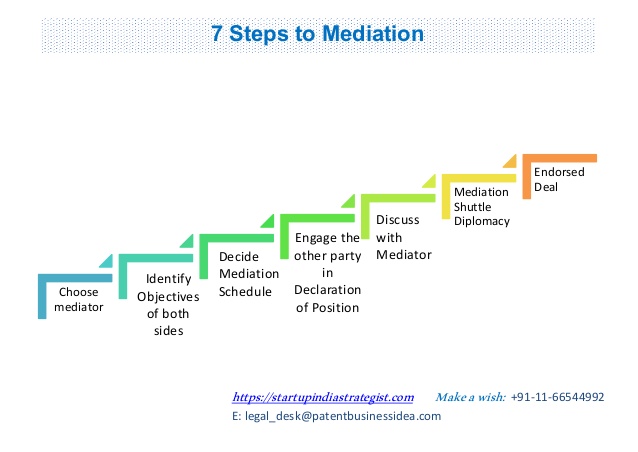

The applicant then submitted a request that the first respondent fulfil its end of the Inter se agreement. As the guarantor, the second respondent agreed to assume liability for the applicant under the terms of the Inter se agreement if the first respondent broke its end of the bargain. Arbitration procedures were initiated by the petitioner against the respondents. The applicant filed a petition with the Supreme Court to form an arbitral tribunal after the respondents refused to name the arbitrator they had selected. The parties accepted the Supreme Court's proposal that Mr. Justice S. N. Variava serve as the only arbitrator in this case. On February 14, 2018, the arbitrator started the pleadings and held a preliminary hearing. The parties mutually decided to add an extra six months to the deadline for concluding the arbitral procedures during this meeting. The deadline for delivering awards has been moved forward to August 2019. Meanwhile, IDBI Bank Ltd. launched an IBC, 2016 bankruptcy process against the first respondent. A moratorium on all steps against the first respondent, including the suspension of arbitral proceedings, was imposed following the NCLT's start of the Corporate Insolvency Resolution Process (CIRP). In a Miscellaneous Application, the petitioner asked for the tribunal's jurisdiction to be extended until the Insolvency and Bankruptcy Code moratorium was lifted. Due to the circumstances at hand, this Court issued an order on January 7, 2020, postponing the application's hearing. On June 3, 2022, the first respondent was freed from the rigorous CIRP processes. The petitioner had filed a request for an interlocutory application, claiming that the Arbitration and Conciliation Act, 1996's change to Section 29A required the arbitration processes to be automatically continued.

Issues Dealt

Does the modified Section 29A apply to arbitration involving foreign commerce?

Which way would the revised 29A apply—forward-looking or backward-looking?

Petitioner's Arguments:

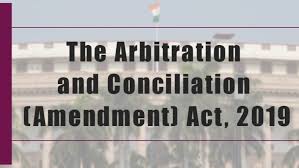

Section 29A was amended in 2019 to remove the 12-month timeframe for issuing an award from the close of pleadings in international commercial arbitration.

It has been suggested that the change should be applied to the ongoing arbitral proceedings because it is procedural. Additionally, the applicant has claimed that if this Court rules that the amended Section 29A criteria do not apply to the ongoing arbitration, the lone arbitrator ought to be granted additional time to complete the arbitration proceedings.

Respondent's Arguments:

The second respondent contended that even with the 2019 modification, international commercial arbitration is still covered by Section 29A. The second respondent asserts that if the applicant's proposed interpretation of Section 29A is accepted, there will be no statutory deadline for international commercial arbitration procedures. The second respondent maintained that the statute did not intend for the court to have no control throughout arbitral proceedings in situations where there is no arbitral institution in place, as in the current situation. The arbitral forum shouldn't have complete influence over how long an arbitration takes, particularly if it is conducted in India and is governed by Indian law.

Decision of Court

Following the 2015 Arbitration and Conciliation Act Amendment, Section 29A[2] of the statute mandated that all commercial arbitration awards be given out within a year of the arbitrator's appointment. This is true for arbitrations conducted both domestically and abroad. The arbitrator's authority to make the award expires if it is not made within this window of time, barring a court extension. International business arbitrations are exempt from the twelve-month deadline, according to a recent change to Section 29A sub-section (1). Rather, the wording indicates that the prize ought to be given "as expeditiously as possible." This implies that even if there isn't a set period for international commercial arbitrations, the ruling needs to be rendered in a fair amount of time. However, domestic arbitrations are not constrained by the twelve months. The modification gives domestic arbitrations more latitude in awarding awards because it does not impact the time limit.

In principle, Section 29A establishes a necessity for the prompt issuing of decisions in commercial arbitrations, taking into account certain factors for both local and foreign cases. The modification gives domestic cases greater freedom and makes the differences between the two types of arbitrations clearer. Taking up the second case problem, it is commonly believed that procedural laws are retrospective unless there is clear and convincing evidence to the contrary. The 2019 Amendment Act contains no provisions indicating future applicability. To resolve the problem of the timeline's application to international business arbitrations, the modification is meant to be remedial. There are no new rights or responsibilities conferred by the aforementioned provision. Therefore, beginning of August 30, 2019, it is essential that the previously indicated clause be considered applicable to all pending arbitration proceedings. All things considered, the modification to Section 29A essentially removes foreign commercial arbitrations from the mandatory time constraints, giving judges more latitude in issuing decisions. It is advised that the change be applied retroactively to all pending arbitrations and that the sole arbiter be given the authority to grant extensions as needed to ensure a prompt and effective process.

The recommendations made by Committee[5] under the leadership of Justice B N Srikrishna were followed in the implementation of the amended Section 29A, which deals with the timeline for arbitration proceedings in India. A special committee was established to evaluate the effectiveness and operation of the arbitration mechanism in the nation. The committee discussed in its findings why the stringent twelve-month term required for domestic arbitrations should not apply to foreign business arbitrations. The committee learned that foreign arbitration associations had voiced their displeasure with the court's enforcement of deadlines. These organizations felt that arbitral bodies already had their procedures for handling cases, thus they didn't think the court needed to be involved in setting deadlines. In several legal countries, the parties concerned determine the timeliness of arbitral procedures by mutual consent, taking into account the unique features and complexities of the dispute in question. Following objections from arbitral institutions over the court's involvement in prolonging deadlines, the legislators amended the Act to remove the requirement for time limits for international commercial arbitrations.

Conclusion

In this particular instance, the Supreme Court decided that because foreign business arbitrations are governed by different laws and regulations, Section 29A does not apply to them. The Court noted that forcing stringent deadlines on complex cross-border disputes will hinder arbitration's effectiveness and calibre, which will damage India's reputation as an arbitration-friendly nation. The aforementioned decision, in my opinion, is a step in the right direction toward strengthening India's standing as a global arbitration hub and preserving the concepts of party autonomy and flexibility in conflict settlement.

- Supreme Court ruled Section 29A doesn't apply to international commercial arbitrations, preserving flexibility.

- The decision safeguards India's reputation as an arbitration-friendly destination.

- Amendment aligns with global arbitration practices, enhancing efficiency without compromising quality.