Latest News

ADR or Litigation? The Court of Appeal's Choice in the Japanese Knotweed Dispute

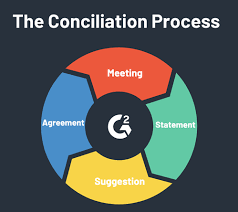

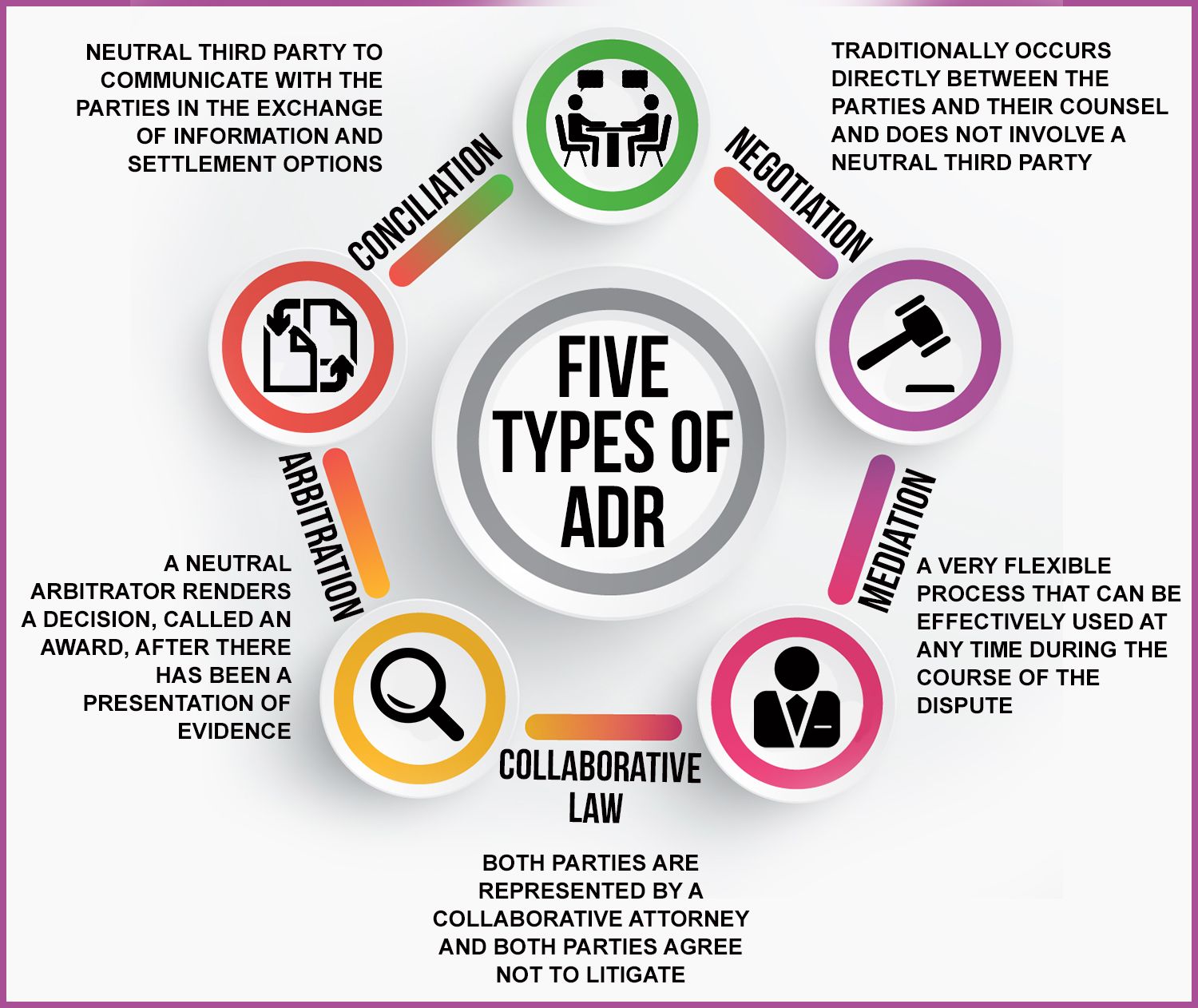

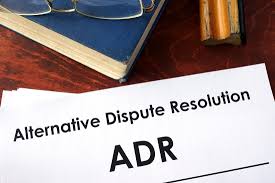

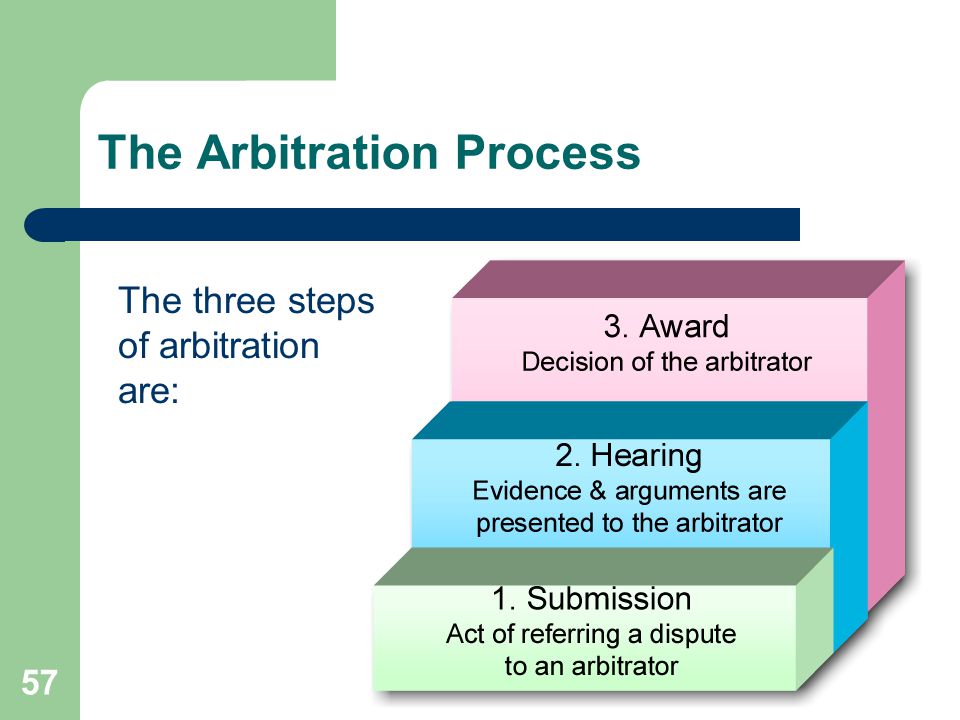

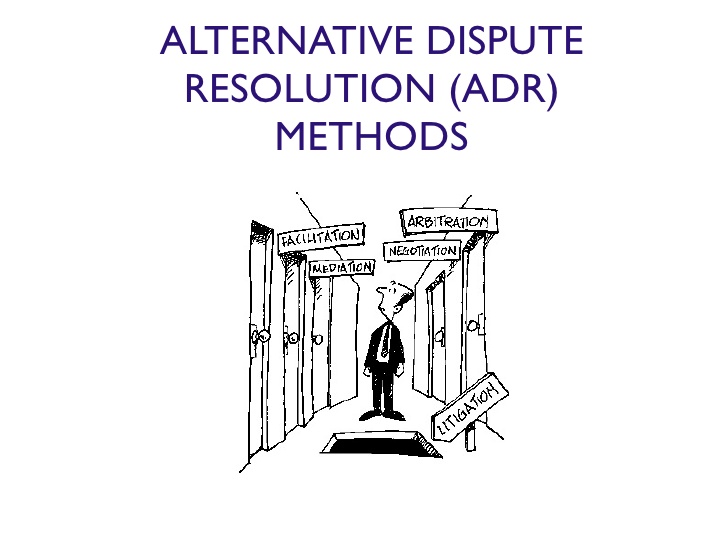

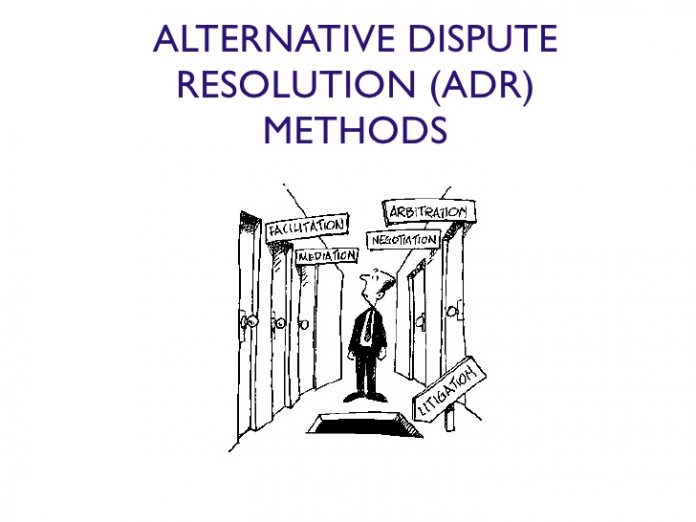

In this article, we will discuss the recent landmark decision of the Court of Appeal in James Churchill v Merthyr Tydfil County Borough Council [2023] EWCA Civ 1416,[1] which confirmed that judges have the power, in appropriate circumstances, to order parties to participate in alternative dispute resolution (ADR).

The background of the case

The case arose from a dispute between Mr Churchill and the Council over the encroachment of Japanese Knotweed onto Mr Churchill's land from the neighbouring land owned by the Council. Mr Churchill sought compensation for the losses he incurred as a result of the nuisance caused by the invasive plant.

The Council denied liability but referred Mr Churchill to their internal Corporate Complaints Procedure, which they claimed was a form of ADR. Mr Churchill ignored the request and issued proceedings in the County Court without engaging in any pre-action communication or negotiation with the Council.

The Council applied for a stay of the proceedings on the basis that Mr Churchill had acted unreasonably and contrary to the Practice Direction for Pre-Action Conduct (PD)[2] by refusing to use their internal complaints procedure. The PD requires parties to consider ADR before commencing litigation and states that litigation should be a last resort.

The first instance decision

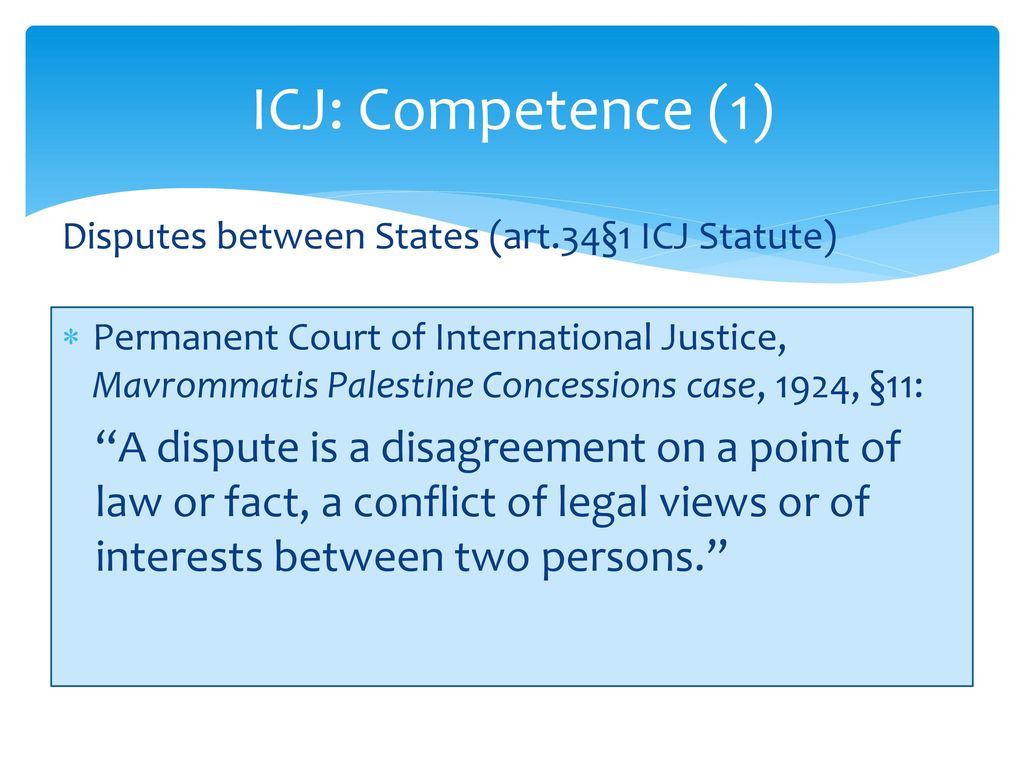

The Deputy District Judge dismissed the Council's application for a stay, holding that he was bound by the authority of Halsey v Milton Keynes General NHS Trust [2004] EWCA Civ 576, [2004] 1 WLR 3002,[3] which stated that:

"To oblige truly unwilling parties to refer their disputes to mediation would be to impose an unacceptable obstruction on their right of access to the court".

The Judge found that Mr Churchill was truly unwilling to participate in ADR and that there was no evidence that ADR had any realistic prospect of success in this case. He also noted that the Council's internal complaints procedure was not a recognised form of ADR and that it lacked independence and impartiality.

The Council appealed the decision, arguing that Halsey was no longer good law and that the court had wide discretion to order parties to engage in ADR under CPR 3.1(2)(m),[4] which allows the court to take any step or make any order to manage the case and further the overriding objective.

The Court of Appeal's decision

The Court of Appeal allowed the appeal and ordered a stay of the proceedings for three months to enable the parties to attempt ADR. The Court held that Halsey was not binding on this issue and that it was based on an outdated view of ADR. The Court recognised that ADR had developed significantly since Halsey and that it was now an integral part of civil justice.

The Court also held that ordering parties to participate in ADR did not infringe their right of access to justice under Article 6 of the European Convention on Human Rights, as long as the order was proportionate, did not cause undue delay or expense, and did not prevent the parties from having their case determined by a court if ADR failed.

The Court set out some factors that may be relevant when deciding whether to order parties to engage in ADR, such as:

- The nature of the dispute and whether it involves issues of law or fact

- The prospects of success of ADR

- The costs and benefits of ADR compared to litigation

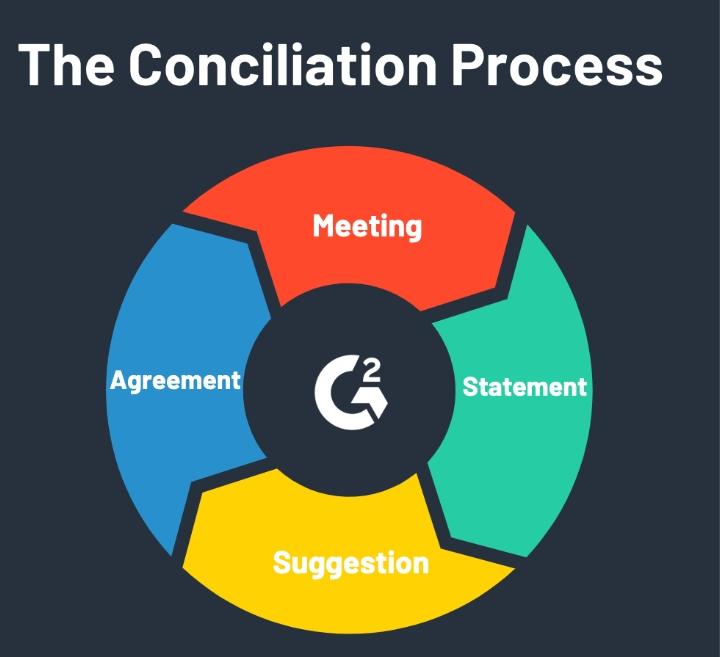

- The availability and suitability of different forms of ADR

- The willingness or unwillingness of the parties to engage in ADR and their reasons

- The stage of the proceedings and whether any previous attempts at ADR have been made

- The impact of an order for ADR on the progress and timetable of the litigation

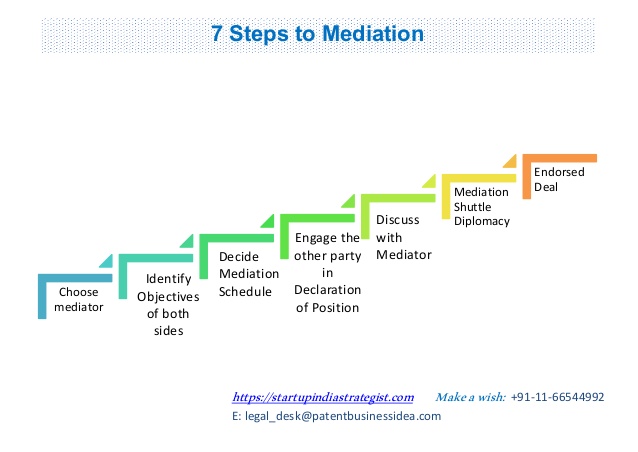

The Court emphasised that these factors were not exhaustive or determinative and that each case must be decided on its own merits. The Court also stressed that ordering parties to engage in ADR did not mean that they had to settle their dispute, but only that they had to make a genuine effort to resolve it through dialogue and cooperation.

In this case, the Court found that there were strong reasons to order ADR, such as:

- The dispute was relatively straightforward and involved factual issues that could be resolved by evidence

- There was a reasonable prospect of success of ADR, as both parties had an interest in avoiding further litigation costs and uncertainty

- The costs and benefits of ADR were favourable, as ADR would be cheaper, quicker and less stressful than litigation

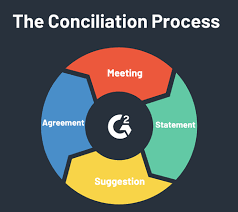

- There were suitable forms of ADR available, such as mediation or early neutral evaluation, which could be conducted online or by telephone

- Mr Churchill's unwillingness to engage in ADR was unreasonable and based on a misunderstanding of its nature and purpose

- The proceedings were at an early stage and no previous attempts at ADR had been made

- The order for ADR would not cause any significant delay or prejudice to the parties, as the stay was limited to three months and the parties could resume litigation if ADR failed

The Court also noted that the Council's internal complaints procedure was not a proper form of ADR and that the parties should use an independent and impartial third party to facilitate ADR.

The implications of the decision

The decision is a significant development in the law and practice of ADR in England and Wales. It confirms that the court has the power and the duty to order parties to engage in ADR in appropriate cases, even if they are unwilling to do so. It also provides clear guidance on how the court will exercise this power and what factors it will consider.

The decision reflects the growing importance and recognition of ADR as a valuable and effective means of resolving disputes. It also encourages parties to adopt a more constructive and cooperative approach to dispute resolution, rather than resorting to litigation as a first option.

The decision is likely to have a positive impact on the use and uptake of ADR, as parties will be more aware of the benefits and risks of ADR and more willing to consider it as a viable alternative to litigation. It may also reduce the costs and delays of litigation, as more disputes will be settled or narrowed by ADR.

The decision is also consistent with the wider policy and legislative initiatives to promote ADR, such as the Civil Justice Council's report on Compulsory ADR (2021),[5] which recommended that compulsory ADR should be introduced in certain types of civil claims, and the Civil Procedure (Amendment) Rules 2021,[6] which introduced a new Practice Direction 57AC on witness statements, which requires parties to confirm whether they have considered using witness evidence in ADR.

Conclusion

The Court of Appeal's decision in James Churchill v Merthyr Tydfil County Borough Council is a landmark ruling that confirms the court's power to order parties to participate in ADR, even if they are unwilling to do so. The decision provides clear guidance on how the court will exercise this power and what factors it will consider. The decision reflects the growing importance and recognition of ADR as a valuable and effective means of resolving disputes. The decision is likely to have a positive impact on the use and uptake of ADR, as parties will be more aware of the benefits and risks of ADR and more willing to consider it as a viable alternative to litigation.

References

[1] "James Churchill v Merthyr Tydfil County Borough Council [2023] EWCA Civ 1416", Judiciary UK, https://www.judiciary.uk/judgments/james-churchill-v-merthyr-tydfil-county-borough-council/

[2] "Practice Direction for Pre-Action Conduct", Ministry of Justice, https://www.justice.gov.uk/courts/procedure-rules/civil/rules/pd_pre-action_conduct

[3] "Halsey v Milton Keynes General NHS Trust [2004] EWCA Civ 576, [2004] 1 WLR 3002", BAILII, https://www.bailii.org/ew/cases/EWCA/Civ/2004/576.html

[4] "Civil Procedure Rules 1998", Ministry of Justice, https://www.justice.gov.uk/courts/procedure-rules/civil/rules

[5] "Compulsory ADR report", Civil Justice Council, Civil-Justice-Council-Compulsory-ADR-report.pdf (judiciary. UK)

[6] "Civil Procedure (Amendment) Rules 2021", Legislation.gov.uk, https://www.legislation.gov.uk/uksi/2021/161/made

- The Court of Appeal confirmed that judges have the power to order parties to engage in ADR, even if they are unwilling to do so.

- The Court of Appeal overruled the previous authority of Halsey, which stated that ordering ADR would infringe the parties' right of access to justice.

- The Court of Appeal set out some factors that may be relevant when deciding whether to order ADR, such as the nature of the dispute, the prospects of success of ADR, and the impact of an order for ADR