Latest News

How closely linked are the UNCITRAL Model Law on International Commercial Arbitration and Indian Arbitration Regulations?

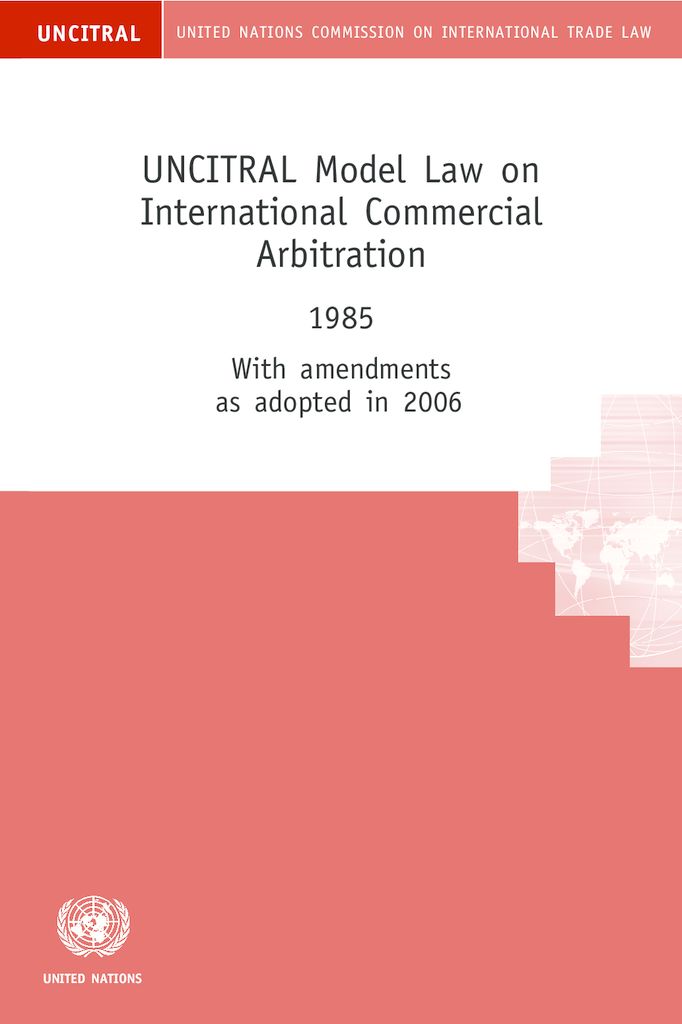

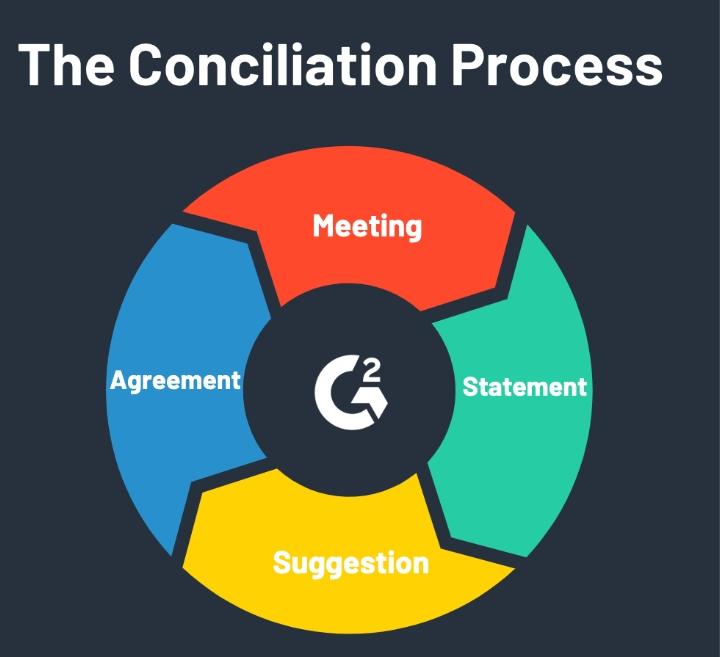

With the advent of globalization, the world saw the interconnection of people and businesses from different parts of the globe and while this led to great partnerships and successful enterprises, it also created a realization for the need to adopt alternate mechanisms for dispute resolutions as traditional courts were unable to handle the growing number of conflicts and disputes that had to be governed on an international platform and resolved as quickly and quietly as possible. This led to the popularity of arbitration, as a method of Alternate Dispute Resolution (ADR), but there was a disparity between states and countries regarding the rules regulating the process and the standards that parties could expect. As a response to this, the United Nations Commission on International Trade Law (UNCITRAL) adopted the Model Law on International Commercial Arbitration on 21st June 1985. The Model Law was adopted with the plea that all states, while setting up their own domestic legislation on arbitration, give due consideration to the Model Law in order to preserve uniformity in the law of arbitral proceedings and to keep in mind the specific needs of international commercial arbitration[1].

Some features of the Model Law are:

- Keeping in mind the disparities existing in countries with relation to international arbitration, the Model Law lays down certain rules and provisions aimed at creating uniformity in international commercial arbitration. However, the provisions are also applicable to domestic arbitration and can be used as a guide to enact modern laws governing domestic arbitration.

- The Model Law defines the substantive aspects of international commercial arbitration by defining “international” – when parties to an agreement have different places of business, or if the place of arbitration, place of performance of contract, place of subject matter of dispute is not domestic, and “commercial” – certain business relationships as illustrated in the Model[2].

- The Model Law also addresses the territorial scope of an arbitral tribunal and the enforceability of an arbitral award. The Model Law enacted in a state would apply if the seat of arbitration is within the territory of that state and the arbitral award pronounced would have global enforcement. However, keeping in mind ‘party autonomy’ in arbitration, the Model Law allows for parties to choose the procedural law applicable to govern their dispute.

- The Model Law also limits the interference of the court, in the spirit of arbitration, allowing judicial intervention only for appointment of arbitrators, challenge and termination of an arbitrator, jurisdiction of an arbitral tribunal, and the setting aside of an arbitral award. It also allows court assistance in taking evidence, recognition of the arbitration agreement, and enforcement of arbitral awards[3].

- The Model Law emphasizes the importance of the arbitration clause or agreement which must be present if parties to a dispute want to proceed with arbitration as a means of resolution. The Model also clarifies the contents of the clause and the recognition of these clauses by the courts.

- With regard to the arbitral tribunals the Model Law states rules on their composition, jurisdiction and conduct of proceedings by the tribunals, keeping in mind the freedom that they have and the will of the parties[4].

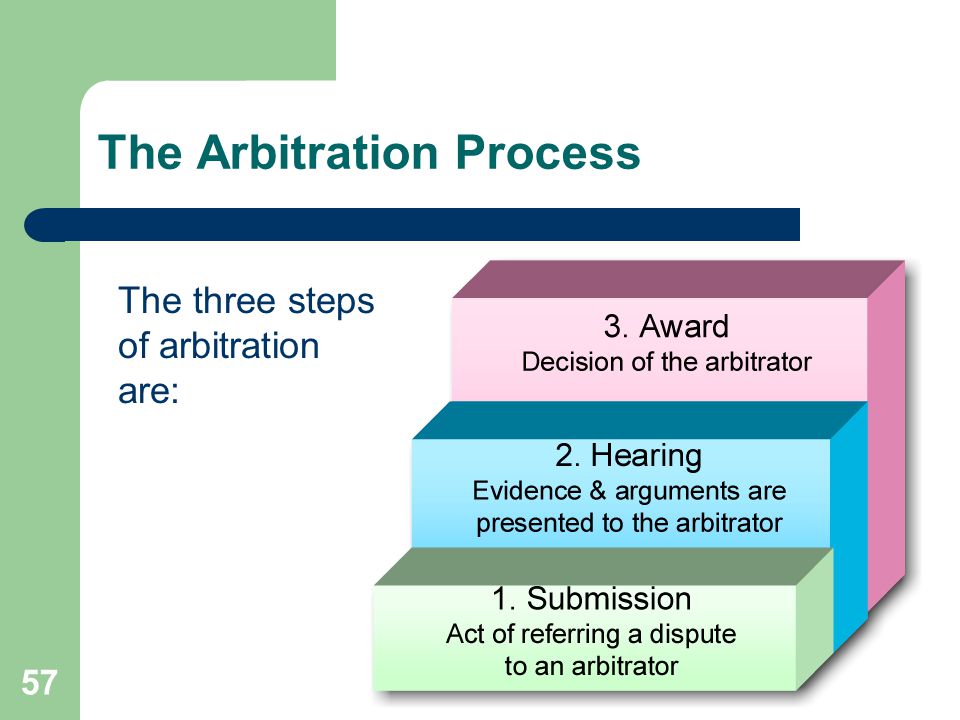

- When it comes to awards, the Model Law sets out rules to be followed for the pronouncement of award, the enforcement of award and setting aside or challenge of the award.

The Model Law was enacted keeping in mind the necessary features in order to eliminate difficulties in regulating international arbitration by providing uniformity in some procedural and substantive practices of arbitration.

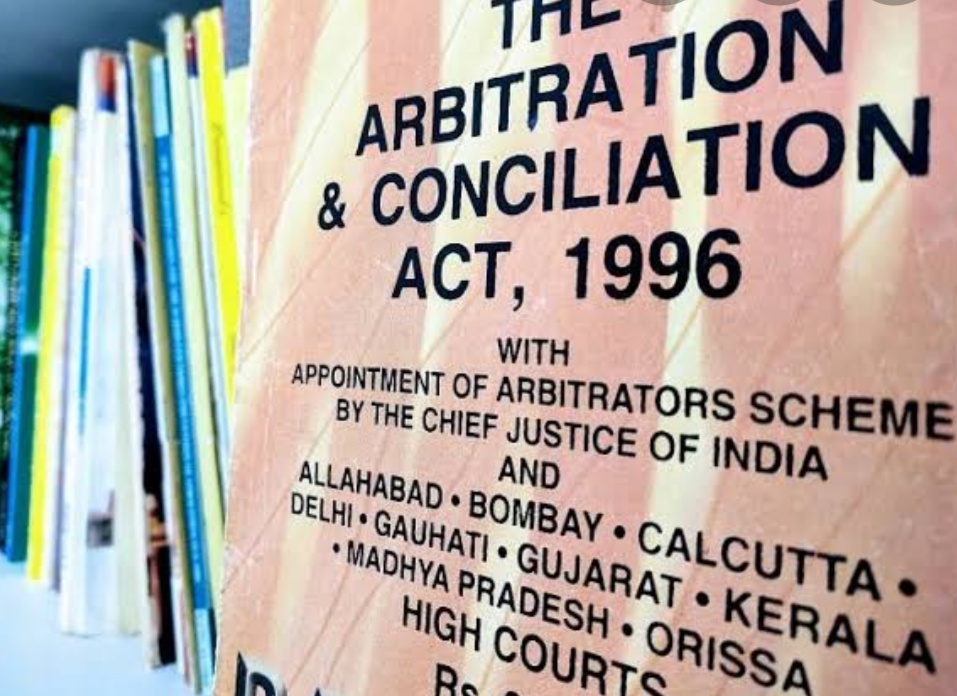

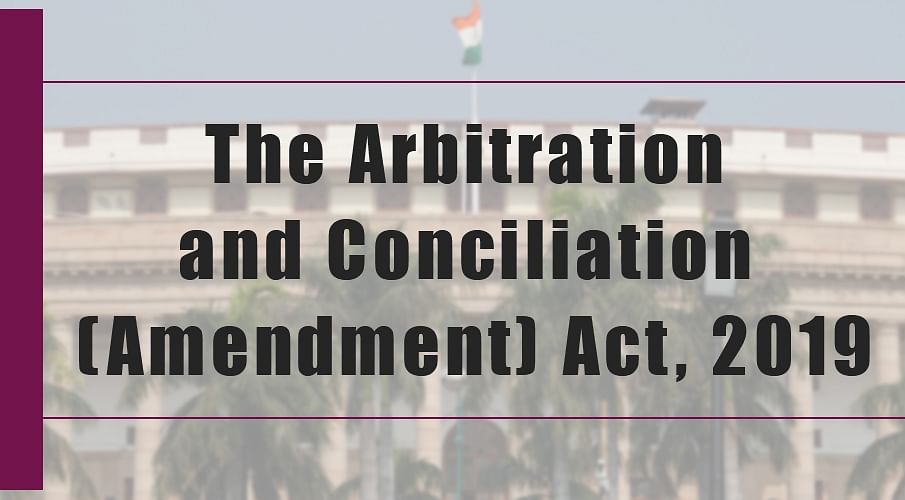

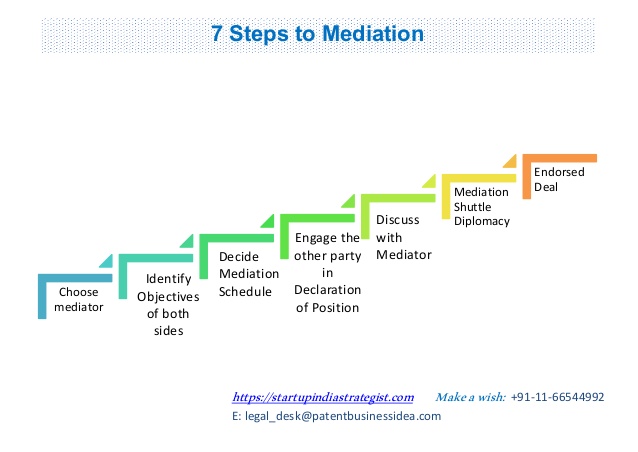

While enacting the Arbitration and Conciliation Act, 1996, the lawmakers in India took into consideration the UNCITRAL Model Law and this can be seen in the Preamble to the Act which specifies that the provisions of the Act are in consonance to and in furtherance of the UNCITRAL Model Law. As a result of this adherence to the Model Law, many of the provisions in the Act of 1996 are in line with the Model Law.

- The Act applies to both domestic and international commercial arbitration, so both the terms have been defined with the definition of international commercial arbitration being quite similar to the definition provided in the Model Law, with the addition of a few new sub-clauses[5].

- The Act also provides for the existence of an arbitration agreement between parties for the commencement of arbitration proceedings. Chapter 2 of the Act lays down the specifications for the arbitration agreement and the intervention of the courts with respect to the agreement[6].

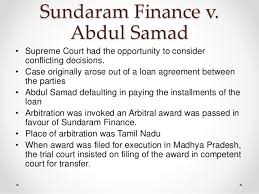

- Chapters 3 and 4 of the Act deals with the composition and jurisdiction of the arbitral tribunals and once again the provisions are in line with the Model Law. The Act empowers the tribunals to rule on its own jurisdiction and allows arbitrators to pronounce awards with limited intervention from the courts.

- Chapter 5 of the Act makes provisions on the conduct of arbitral proceedings keeping in mind the freedom of arbitrators and the will of the parties, much like the Model Law.

- Chapters 6 and 7 deal with the rules to be followed for the pronouncement of award, the enforcement of award and setting aside or challenge of the award, and this is important because it allows for the intervention of the court but only in certain circumstances which are mentioned under Section 34(2)[7].

- Chapter 8 states that arbitral awards are final and binding on the parties and all courts and once again it is in consonance with the principles of arbitration and the Model Law[8].

It is therefore evident that the Indian law on arbitration, the Arbitration and Conciliation Act, 1996, follows the UNCITRAL Model Law almost down to the T but with the amendments to the Act in 2005 and 2019, the Act has set out to make India a hub for international Commercial Arbitration and in doing so has deviated from some of the rules of arbitration like judicial intervention.

[1] Faculty, UNCITRAL Secretariat Explanation of the Model Law, SMU, (Jun. 7th, 2018, 2:23 PM), http://faculty.smu.edu/pwinship/arb-24.htm.

[2] United Nations Commission on International Trade Law, UNCITRAL Model Law on International Commercial Arbitration 1985: with amendments as adopted in 2006 (Vienna: United Nations, 2008), available at https://www.uncitral.org/pdf/english/texts/arbitration/ml-arb/06-54671_Ebook.pdf.

[3] Editor, UNCITRAL Model Rules of Arbitration and Indian Law, Shodhganga, (Aug. 25th, 2017, 4:55 PM), https://shodhganga.inflibnet.ac.in/bitstream/10603/129366/9/09_chapter%204.pdf.

[4] Supra note 1.

[5] Editor, The Arbitration and Conciliation Act, 1996 – An Analytical Outlook, Shodhganga, (Apr. 10, 2020, 2:56 PM), https://shodhganga.inflibnet.ac.in/bitstream/10603/201576/10/10_chapter%204.pdf.

[6] Abhishek Bhargava, Salient Features of Arbitration and Conciliation Act, 1966, India Institute of Legal Science, (Apr. 11, 2020, 3:09 PM), https://www.iilsindia.com/blogs/salient-features-of-arbitration-and-conciliation-act-1996/.

[7] The Arbitration and Conciliation Act, 1996, No. 26 Acts of Parliament, 1996 (India).

[8] Anil Satyagraha, Salient Features of the Arbitration Act and Conciliation Act, 1966, LawyersClub India (Dec. 27, 2016, 1:24 PM), https://www.lawyersclubindia.com/articles/Salient-features-of-the-arbitration-and-conciliation-act-1996-7773.asp.

- Arbitration

- UNCITRAL Model Law on International Commercial Arbitration

- Arbitration and Conciliation Act, 1996