Latest News

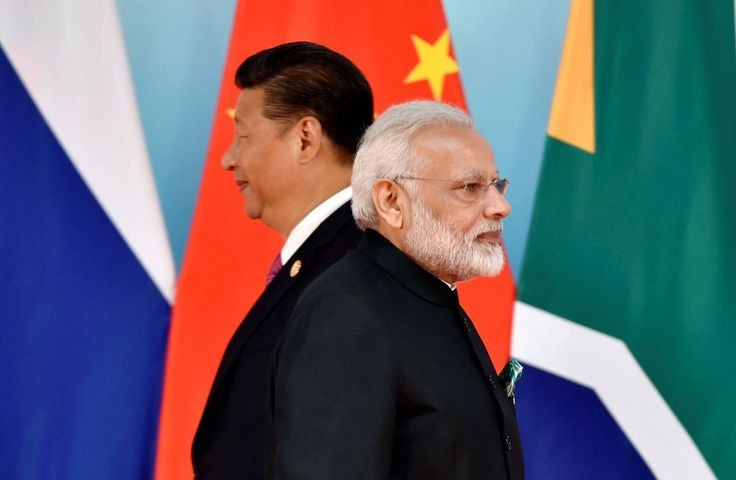

How India and Singapore Approach Party Autonomy and Choice of Law

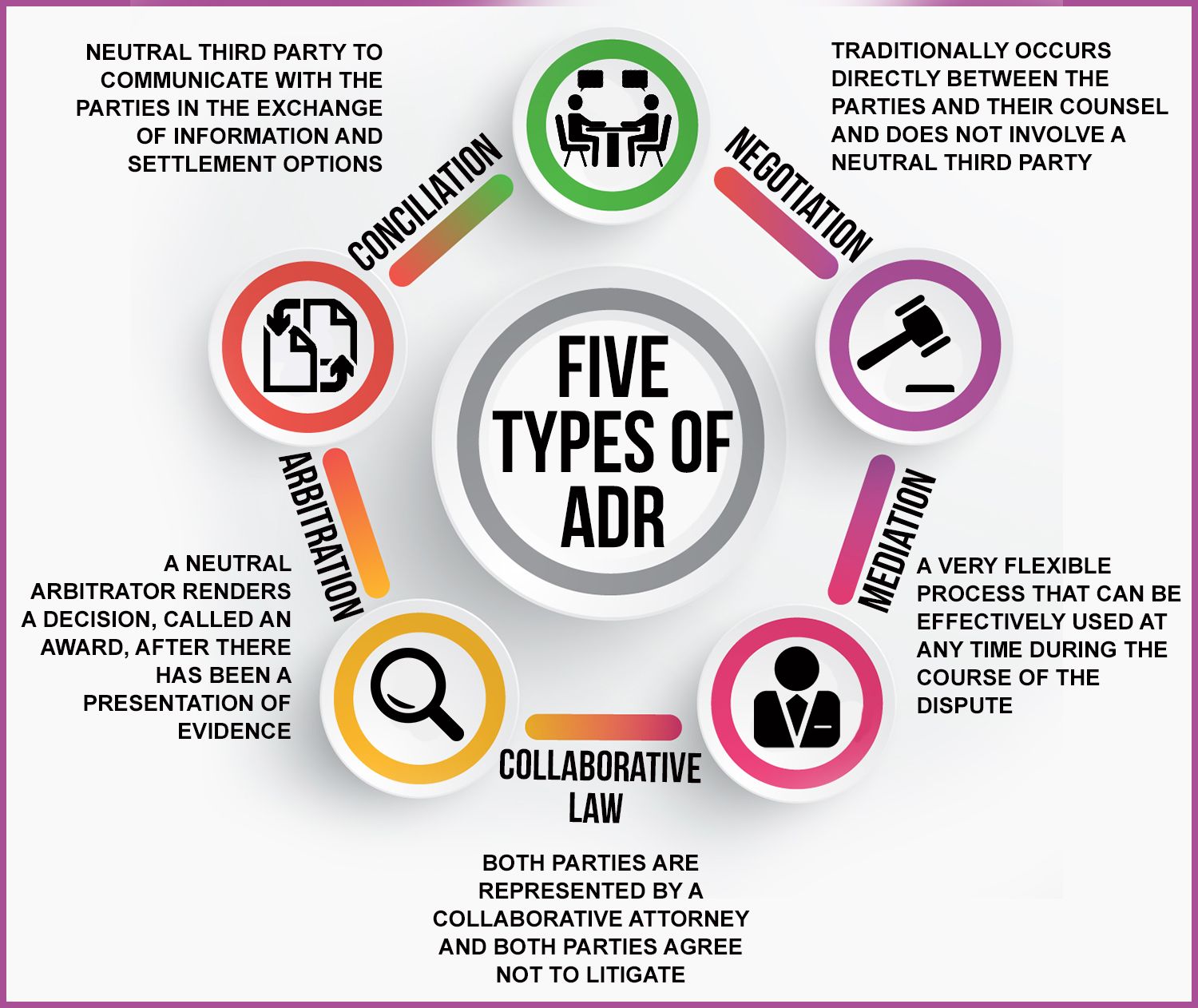

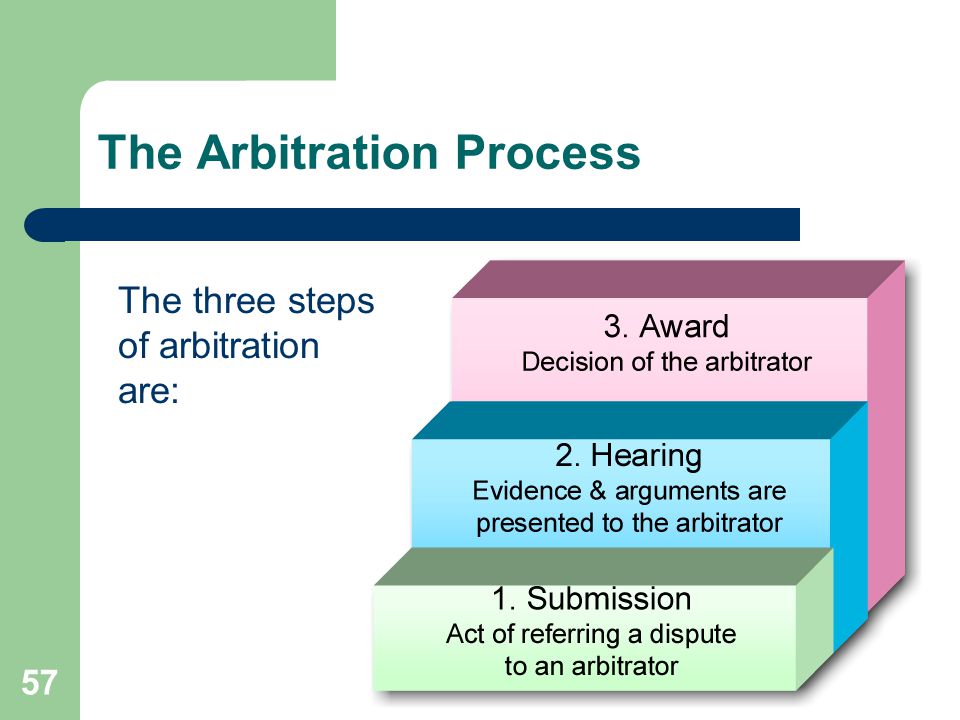

Arbitration stands as a preferred alternative to traditional court proceedings for resolving disputes. It grants parties significant autonomy, enabling them to dictate crucial elements of the arbitration process, including the applicable laws, procedural regulations, arbitrator selection, and arbitration venue. This autonomy, often referred to as party autonomy, constitutes a cornerstone principle in arbitration practice, emphasizing the parties' liberty to tailor the dispute resolution mechanism to their specific needs and preferences.

However, party autonomy is not absolute, and it may be subject to certain limitations imposed by the law or public policy of the relevant jurisdictions. In particular, when parties from different countries choose to arbitrate their disputes, they may face different legal regimes that may affect their choice of seat and law. Moreover, when parties from the same country choose a foreign seat or law for their arbitration, they may encounter additional challenges in terms of the enforceability and validity of their arbitration agreement and award.

In this article, we will compare the legal frameworks and judicial approaches of India and Singapore regarding party autonomy in arbitration, especially in cases involving Indian parties. We will also highlight some of the recent developments and trends in both jurisdictions that may have implications for parties who wish to arbitrate their disputes in Singapore or India.

India: A Pro-Arbitration Jurisdiction?

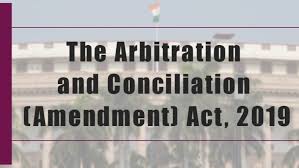

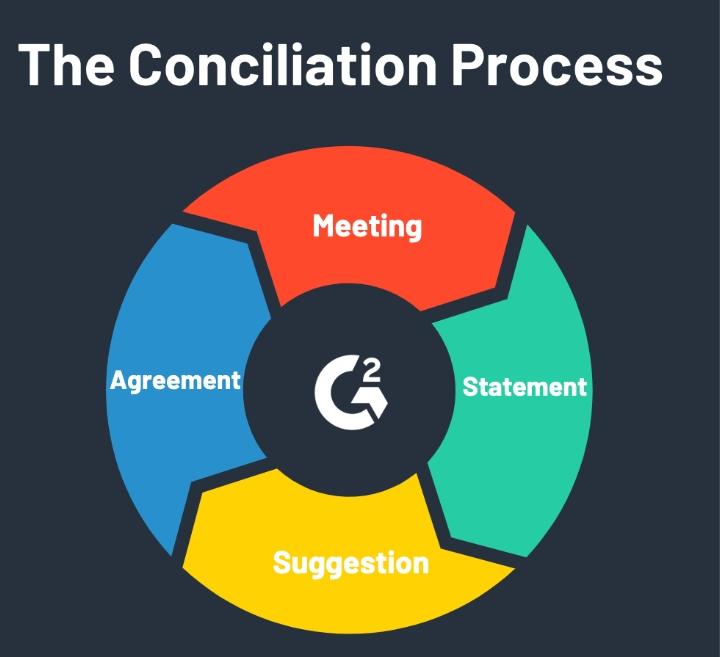

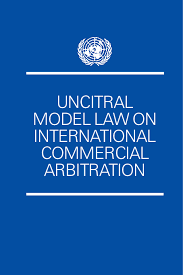

India has a long history of arbitration, dating back to ancient times when disputes were resolved by panchayats (village councils) or nyaya panchayats (judicial councils). However, modern arbitration in India is governed by the Arbitration and Conciliation Act, 1996 (the Act), which is based on the UNCITRAL Model Law on International Commercial Arbitration. The Act applies to both domestic and international arbitrations, and it provides for a comprehensive framework for conducting arbitration proceedings and enforcing arbitration awards.

The Act also recognizes party autonomy as a guiding principle of arbitration, and it allows parties to choose the law governing their arbitration agreement, the law governing their substantive contract, the rules governing their arbitration proceedings, and the seat of their arbitration. However, these choices are subject to certain restrictions imposed by the Act or by Indian public policy.

For instance, Section 28 of the Act provides that in arbitration proceedings other than international commercial arbitration where the seat is in India, unless the parties have agreed otherwise, the tribunal shall decide the dispute per the substantive law for the time being in force in India.[1] Similarly, Section 34 of the Act provides that an award made in India may be set aside by an Indian court if it is contrary to the public policy of India, which includes not only the fundamental policy of Indian law but also justice, morality, or basic notions of human rights.[2]

Another issue that has been controversial in India is whether two Indian parties can choose a foreign seat or law for their arbitration. This issue has been debated for years, with conflicting rulings from various high courts. On one hand, some High Courts have held that such a choice is permissible and does not violate Indian public policy, as long as there is no element of evasion or avoidance of Indian law or jurisdiction.[3] On the other hand, some High Courts have held that such a choice is impermissible and contrary to Indian public policy, as it would amount to ousting Indian courts from supervising or enforcing such arbitrations.[4]

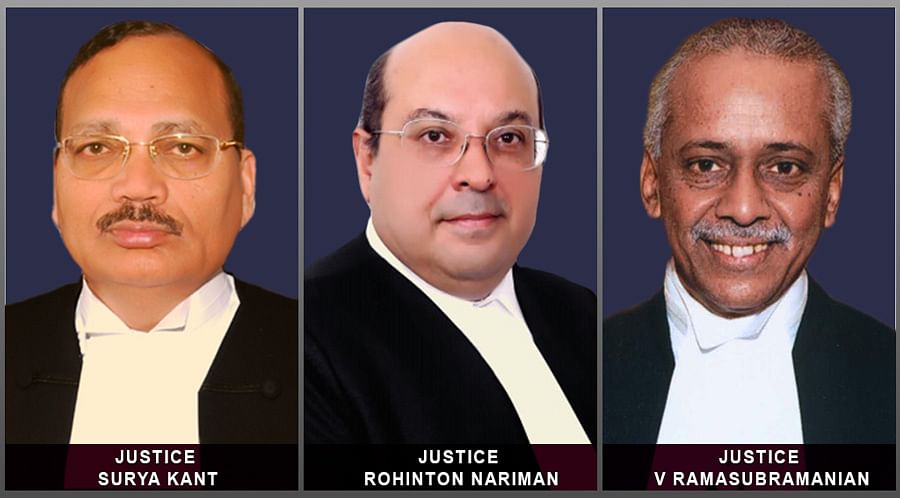

However, in a landmark ruling in 2021, the Supreme Court of India settled this issue by holding that two Indian parties can choose a foreign seat of arbitration and that such a choice would not be contrary to Indian public policy.[5] The Supreme Court also held that an award resulting from such an arbitration would be enforceable as a foreign award under Part II of the Act, which deals with awards made under the New York Convention or the Geneva Convention.[6] The Supreme Court reasoned that there was nothing in the Act that precluded Indian parties from choosing a foreign seat of arbitration and that party autonomy and freedom of contract must be upheld.

The Supreme Court's ruling has been widely welcomed by the arbitration community as a progressive and pro-arbitration decision that clears the decks for giving effect to party autonomy in arbitration involving Indian parties. It also brings India into line with other major arbitration jurisdictions, such as Singapore and England, where two domestic parties can choose a foreign seat or law for their arbitration.

Singapore: A Leading Arbitration Hub

Singapore's success as an arbitration hub can be attributed to several factors, such as its strategic location, its stable and efficient legal system, its pro-arbitration judiciary, its modern and user-friendly arbitration legislation, its world-class arbitration institutions and facilities, and its diverse and talented pool of arbitration practitioners and experts.

Singapore's arbitration legislation is based on the UNCITRAL Model Law, with some modifications to suit the local context. The main legislation governing arbitration in Singapore is the Arbitration Act (AA), which applies to domestic arbitrations, and the International Arbitration Act (IAA), which applies to international arbitrations. Both the AA and the IAA recognize party autonomy as a core principle of arbitration, and they allow parties to choose the law governing their arbitration agreement, the law governing their substantive contract, the rules governing their arbitration proceedings, and the seat of their arbitration. However, these choices are also subject to certain limitations imposed by Singaporean law or public policy.

For example, Section 15 of the AA and Section 19 of the IAA provide that in an arbitration with its seat in Singapore, unless the parties have agreed otherwise, the tribunal shall decide the dispute following the law chosen by the parties as applicable to the substance of the dispute. This means that parties can choose a foreign substantive law if they have chosen Singapore as their seat of arbitration. However, Section 24 of the AA and Section 31 of the IAA provide that an award made in Singapore may be set aside by a Singapore court if it is contrary to the public policy of Singapore, which includes not only the fundamental policy of Singapore law but also international public policy.

Another issue that has been relevant for Singapore is whether two foreign parties can choose Singapore as their seat of arbitration. This issue has been addressed by the Singapore courts in several cases, where they have affirmed that two foreign parties can choose Singapore as their seat of arbitration and that such a choice would not be invalid or ineffective.[7] The Singapore courts have also held that by choosing Singapore as their seat of arbitration, two foreign parties would be subject to the supervisory jurisdiction of the Singapore courts and the applicable provisions of the IAA.[8]

The Singapore courts have also been supportive of party autonomy in arbitration involving Indian parties. In a recent case, the Singapore High Court enforced an award made in Singapore under SIAC rules between two Indian parties who had chosen Singapore as their seat of arbitration and Indian law as their substantive law. The High Court rejected the argument that such an award was contrary to Indian public policy or that it violated any mandatory provisions of Indian law.[9] The High Court also noted that the Supreme Court of India had recently confirmed that two Indian parties can choose a foreign seat of arbitration.

The High Court's decision has been seen as a positive development for Singapore-seated arbitration of Indian disputes, as it demonstrates that Singapore courts respect party autonomy and enforce foreign awards in accordance with their obligations under the New York Convention. It also shows that Singapore courts are familiar with Indian law and practice and are capable of dealing with complex issues arising from cross-border disputes involving Indian parties.

Conclusion

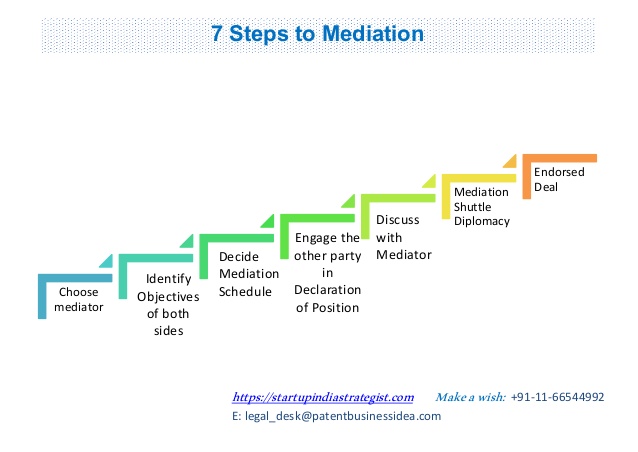

Party autonomy is a key feature of arbitration that allows parties to tailor their dispute resolution process according to their needs and preferences. However, party autonomy is not unlimited, and it may be subject to certain legal or public policy constraints depending on the jurisdictions involved. Therefore, parties should be aware of the potential implications and challenges of choosing a particular seat or law for their arbitration.

India and Singapore are both pro-arbitration jurisdictions that recognize party autonomy as a fundamental principle of arbitration. However, they have different legal frameworks and judicial approaches regarding party autonomy in arbitration, especially in cases involving Indian parties. In this article, we have compared some of the similarities and differences between India and Singapore on this topic, and we have highlighted some of the recent developments and trends in both jurisdictions that may have implications for parties who wish to arbitrate their disputes in Singapore or India.

References

[1] See Section 28(1)(a) of the Act.

[2] See Section 34(2)(b)(ii) of the Act.

[3] See Sasan Power Ltd v North American Coal Corporation India Pvt Ltd (2016) SCC OnLine MP 5559; GMR Energy Ltd v Doosan Power Systems India Pvt Ltd (2017) SCC OnLine Del 11625.

[4] See Addhar Mercantile Pvt Ltd v Shree Jagdamba Agrico Exports Pvt Ltd (2015) SCC OnLine Bom 7752; TDM Infrastructure Pvt Ltd v UE Development India Pvt Ltd (2008) 14 SCC 271.

[5] See PASL Wind Solutions Pvt Ltd v GE Power Conversion India Pvt Ltd (2021) SCC OnLine SC 331.

[6] See Sections 44-52 of Part II of

[7] Westbridge Ventures II Investment Holdings v Anupam Mittal [2021] SGHC 244

[8] International arbitration law and rules in Singapore| CMS

[9] Vijay Karia vs Prysmian Cavi E Sistemi Srl on 13 February, 2020 (indiankanoon.org)

- This article delves into the concept of party autonomy and its limitations in arbitration.

- This article discusses the legal frameworks and judicial approaches of India and Singapore.

- The implications of the recent landmark decision of the Supreme Court of India in PASL Wind Solutions Private Limited v GE Power Conversion India Private Limited.