Latest News

Arbitrability Scope and Limits in India, Singapore and Hong Kong

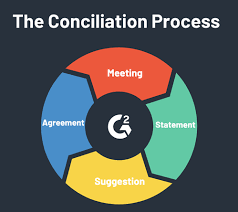

Arbitrability is the question of whether a dispute can be resolved by arbitration or not. Different jurisdictions have different rules and practices regarding the arbitrability of various types of disputes, such as intellectual property, insolvency, competition, etc. In this blog post, we will compare and contrast the legal frameworks and recent developments in three major arbitration hubs: India, Singapore, and Hong Kong. These hubs are chosen because they represent different legal traditions, such as common law (India and Hong Kong), civil law (Singapore), and mixed law (Hong Kong), which may influence their attitudes towards arbitration and arbitrability.

India

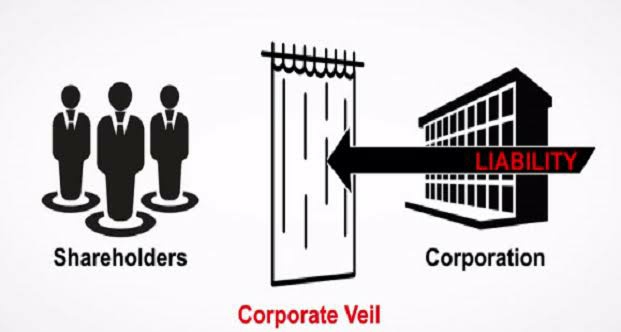

India follows the test laid down by the Supreme Court in Booz Allen Hamilton v. SBI Home Finance[1] for determining the arbitrability of disputes. According to this test, all disputes that concern rights in rem (i.e., rights available against the world at large) are non-arbitrable, while disputes that concern rights in personam (i.e., rights available against specific persons) are arbitrable. The Supreme Court also provided a list of examples of non-arbitrable disputes, such as criminal offences, matrimonial matters, guardianship matters, insolvency matters, testamentary matters, etc.

However, this test has been criticized for being too rigid and simplistic, as it does not take into account the nature and complexity of modern commercial disputes, which may involve both rights in rem and rights in personam. Moreover, this test does not reflect the international trend of recognizing the arbitrability of various types of disputes, such as intellectual property, competition, consumer protection, etc.

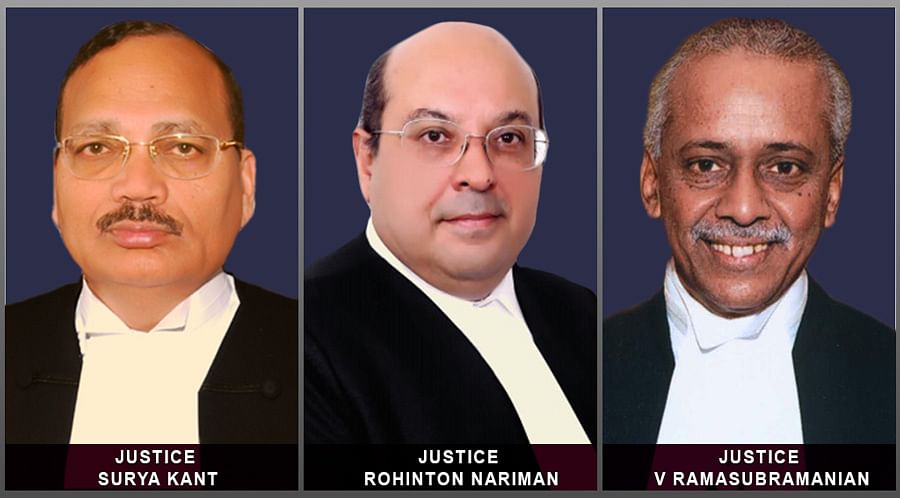

Recently, the Supreme Court clarified and refined the test of arbitrability in Vidya Drolia v. Durga Trading Corporation.[2] In this case, the Supreme Court held that the test of arbitrability is not only based on the nature of the rights involved but also on the following factors:

whether the dispute affects third-party rights or public interest;

whether the dispute requires specialised expertise or centralised adjudication;

Whether the dispute is expressly or impliedly non-arbitrable under mandatory statutory provisions.

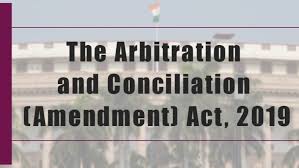

The Supreme Court also held that the arbitrability of a dispute is to be decided by the courts at the pre-arbitration stage (i.e., when an application is filed under Section 8 or 11 of the Arbitration and Conciliation Act, 1996) unless there is a valid agreement between the parties to refer the question of arbitrability to the arbitral tribunal. The Supreme Court also overruled some of its previous judgments that held certain types of disputes to be non-arbitrable, such as fraud,[3] trust,[4] lease,[5] etc.

Singapore

Singapore is a leading arbitration hub in Asia and has a modern and pro-arbitration legal framework based on the UNCITRAL Model Law. The Arbitration Act (AA) governs domestic arbitrations, while the International Arbitration Act (IAA) governs international arbitrations. Both acts provide for the power of arbitral tribunals and courts to grant interim measures in aid of arbitration.

The AA and the IAA do not explicitly define what types of disputes are arbitrable or non-arbitrable. However, Section 11(1) of the AA and Section 11(1) of the IAA state that any dispute that parties have agreed to submit to arbitration under an arbitration agreement may be determined by arbitration unless it is contrary to public policy to do so. Therefore, the test of arbitrability in Singapore is based on public policy considerations.

The Singapore courts have adopted a liberal and pragmatic approach to arbitrability and have recognised the arbitrability of various types of disputes, such as intellectual property,[6] insolvency,[7] competition,[8] etc. The Singapore courts have also held that even if a dispute involves statutory rights or obligations, it does not necessarily mean that it is non-arbitrable unless there is a clear legislative intent to exclude arbitration or there are overriding public policy reasons to do so.[9]

The Singapore courts have also upheld the principle of kompetenz-kompetenz and have held that arbitral tribunals have the primary jurisdiction to decide on their jurisdiction, including the question of arbitrability.[10] However, the courts can review the arbitral tribunal's decision on arbitrability at the post-award stage (i.e. when an application is filed for setting aside or enforcement of an award).[11]

Hong Kong

Hong Kong is another leading arbitration hub in Asia and has a modern and pro-arbitration legal framework based on the UNCITRAL Model Law. The Arbitration Ordinance (AO) governs both domestic and international arbitrations in Hong Kong and provides for the power of arbitral tribunals and courts to grant interim measures in aid of arbitration.

The AO does not explicitly define what types of disputes are arbitrable or non-arbitrable. However, Section 103(1) of the AO states that any dispute that the parties have agreed to submit to arbitration under an arbitration agreement may be determined by arbitration unless the arbitration agreement is void, inoperative or incapable of being performed, or the dispute is not capable of determination by arbitration. Therefore, the test of arbitrability in Hong Kong is based on the validity and scope of the arbitration agreement and the capability of determination by arbitration.

The Hong Kong courts have adopted a liberal and pro-arbitration approach to arbitrability and have recognised the arbitrability of various types of disputes, such as intellectual property,[12] insolvency,[13] competition,[14] etc. The Hong Kong courts have also held that even if a dispute involves statutory rights or obligations, it does not necessarily mean that it is non-arbitrable unless there is a clear legislative intent to exclude arbitration or there are overriding public policy reasons to do so.[15]

The Hong Kong courts have also upheld the principle of kompetenz-kompetenz and have held that arbitral tribunals have the primary jurisdiction to decide on their jurisdiction, including the question of arbitrability.[16] However, the courts can review the arbitral tribunal's decision on arbitrability at the pre-arbitration stage (i.e. when an application is filed for stay of court proceedings) or at the post-award stage (i.e. when an application is filed for setting aside or enforcement of an award).[17]

Conclusion

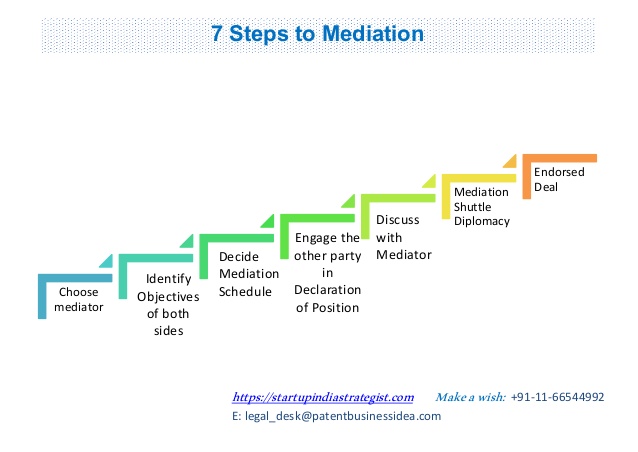

From the above comparison, it can be seen that India, Singapore and Hong Kong have different tests and approaches to the arbitrability of disputes. India follows a rights-based test with some refinements, Singapore follows a public policy-based test with a liberal interpretation, and Hong Kong follows a validity and capability-based test with a pro-arbitration attitude. However, all three jurisdictions have shown a tendency to recognize the arbitrability of various types of disputes, especially those arising from commercial transactions, and to respect the parties' choice of arbitration as a mode of dispute resolution.

References

[1] Booz Allen Hamilton v. SBI Home Finance Ltd., (2011) 5 SCC 532.

[2] Vidya Drolia v. Durga Trading Corporation, (2021) 2 SCC 1.

[3] N. Radhakrishnan v. Maestro Engineers, (2010) 1 SCC 72.

[4] Vimal Kishor Shah v. Jayesh Dinesh Shah, (2016) 8 SCC 788.

[5] Himangni Enterprises v. Kamaljeet Singh Ahluwalia, (2017) 10 SCC 706.

[6] Warner Bros Entertainment Inc v Global Ascent Ltd., [2008] SGHC 153.

[7] Larsen Oil & Gas Pte Ltd v Petropod Ltd., [2011] SGHC 21.

[8] Competition Commission v Nutanix Hong Kong Ltd., [2020] HKCFI 1459.

[9] Tomolugen Holdings Ltd v Silica Investors Ltd., [2016] 1 SLR 373.

[10] FirstLink Investments Corp Ltd v GT Payment Pte Ltd., [2014] SGHCR 12.

[11] Aloe Vera of America Inc v Asianic Food (S) Pte Ltd., [2006] SGHC 78.

[12] Gao Haiyan v Keeneye Holdings Ltd., [2012] HKCFI 279.

[13] Re Legend International Resorts Ltd., [2006] HKCFI 1067.

[14] Competition Commission v Nutanix Hong Kong Ltd., [2020] HKCFI 1459.

[15] Astro Nusantara International BV v PT Ayunda Prima Mitra, [2018] HKCFA 12.

[16] China International Fund Ltd v Dennis Lau & Ng Chun Man Architects & Engineers (HK) Ltd., [2015] HKCFI 2280.

[17] Astro Nusantara International BV v PT Ayunda Prima Mitra, [2018] HKCFA 12.

- Arbitrability refers to the question of what types of issues can and cannot be submitted to arbitration and whether specific classes of disputes are exempt from arbitration proceedings.

- Different jurisdictions have different rules and practices regarding the availability, scope and enforceability of interim measures ordered by arbitral tribunals or courts in aid of arbitration.

- India follows the Booz Allen Hamilton test, which excludes disputes involving rights in rem (e.g. IP rights) from arbitration. However, Indian courts can grant interim relief for foreign arbitrations.