Latest News

Building on Legacy: An Insight into the Proposed Reforms to the UK's Arbitration Act 1996

Introduction

The United Kingdom has long been recognized for its efficacious arbitration environment. The credit for this is owed largely to the Arbitration Act 1996. The Ministry of Justice proposed a review of the 1996 Act in March 2021, and the Law Commission undertook the same in January 2022. In the words of the Bar Council Chairman, Nick Kneall KC: ‘It is important to legislate to make modest changes to the arbitration regime which the law commission has recommended to maintain and enhance that reputation.’[1] In its review,[2] the Law Commission made several recommendations regarding the reforms necessary for adoption or reconstruction to ensure the best arbitration practices in the UK. This article provides a brief overview of these recommended reforms.

Confidentiality in Arbitration

Confidentiality Overview

Confidentiality in arbitration revolves around the safeguarding of information, who has access to it and the purpose for which they have such access. It also attaches to information disclosed during proceedings. While arbitral rules often include provisions on confidentiality, the Arbitration Act 1996 in England and Wales lacks specific provisions on this matter.

Conclusion

Despite calls for a statutory rule on confidentiality, the majority consensus, including from consultees, supports maintaining the status quo. Parties can currently agree to keep their arbitration confidential, offering flexibility that aligns with various arbitral contexts.

Challenges of Codifying Confidentiality

The diversity in arbitral rules and the evolving nature of the law make codifying a singular rule on confidentiality impractical. The existing approach, allowing the development of confidentiality rules through case law and arbitral practices, remains robust.

Arbitrator Independence, Disclosure, Removal, and Resignation

Understanding Impartiality, Independence, and Disclosure

Impartiality, independence, and disclosure form the triad that assures fair arbitration. While the Arbitration Act 1996 explicitly addresses impartiality[3], questions arise regarding the need for statutory duties of independence and disclosure.

Independence: A Balanced Perspective

Independence requires an arbitrator to not have any connection to either party or the dispute itself. A consensus has emerged against stipulating a statutory duty of independence for arbitrators. Acknowledging the practical challenges of achieving complete independence, such as the limited number of arbitrators in specialized areas, the focus remains on arbitrators' impartiality and the impact of any connections on the perception of bias.

Disclosure: Codifying a Common Law Principle

Building on the common law principle outlined in Halliburton v Chubb (2020),[4] a recommendation supports codifying the duty of arbitrators to disclose circumstances raising justifiable doubts about their impartiality. This duty, deemed essential for upholding the integrity of arbitration, aligns with international best practices.

Extending Duty of Disclosure

The recommendation further suggests that arbitrators must disclose any circumstances they are aware of or ‘should reasonably be aware of.’ This ensures a higher standard for disclosure, promoting transparency and mitigating potential conflicts.

Removal and Resignation of Arbitrators

The debate on arbitrator resignation highlighted potential liabilities, with a recommended reform proposing that arbitrators incur no liability for resignation unless it is deemed unreasonable. Striking a balance between deterring inappropriate resignations and avoiding delays and costs to arbitral parties is a primary consideration.

In cases of removal, stakeholders recommended that arbitrators should not incur costs liability unless they have acted in bad faith. This aligns with the Act's intention and prevents unintended challenges and compromise of arbitrator neutrality.

Challenging Arbitral Awards: Substantive Jurisdiction

Defining Substantive Jurisdiction

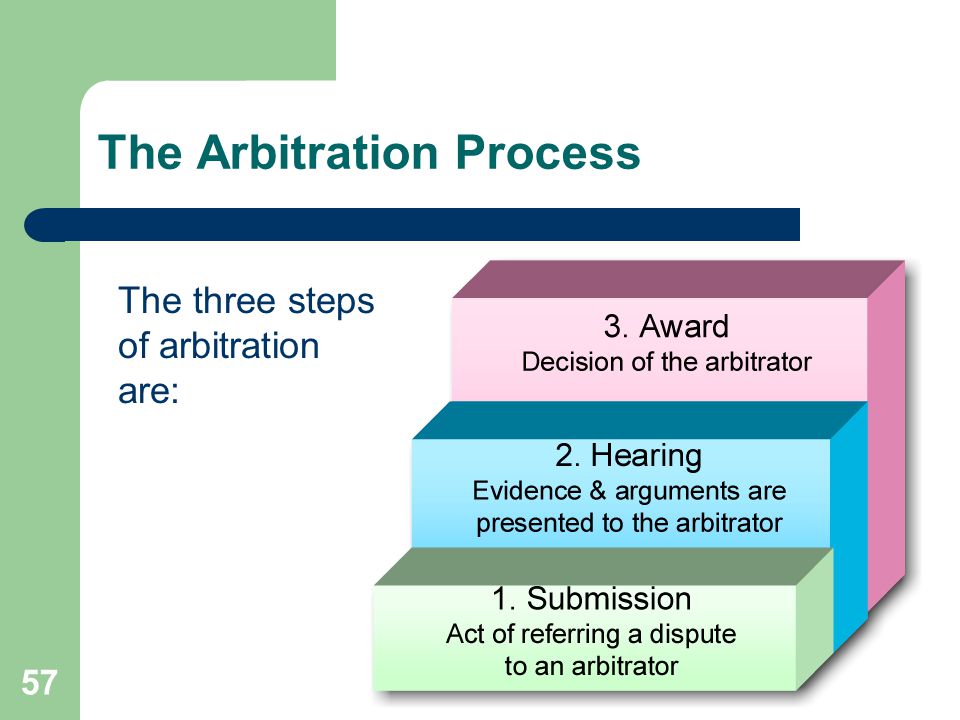

The substantive jurisdiction of an arbitral tribunal includes the validity of the arbitration agreement, the tribunal's constitution, and the matters submitted to arbitration. Disputes over jurisdiction can be raised during arbitral proceedings or challenged before the court under Section 67 of the Arbitration Act 1996.

Balancing Kompetenz-Kompetenz

The principle of competence-competence allows the tribunal to rule, on its jurisdiction, a decision subject to challenge under Section 67. However, the recommendation calls for a nuanced approach, emphasizing that a full rehearing should be avoided unless necessary in the interests of justice.

Reforms and Remedies

Proposed reforms include amendments to Section 67, aligning remedies with Sections 68 and 69, and explicitly granting arbitral tribunals the power to award costs in jurisdictional challenges.

Governing Law of Arbitration Agreements

Complexities in Governing Law

The governing law of arbitration agreements involves intricate considerations, including the law chosen by the parties and the law of the seat. The Enka v Chubb[5] decision provides a framework but introduces complexities and risks of applying foreign laws.

Proposed Default Rule

To address uncertainties, the governing law of an arbitration agreement must be either the law expressly agreed upon by the parties or, in the absence of such agreement, the law of the seat.

Balancing Certainty and Flexibility

This default rule aims to simplify complexities, align with the seat's law, and provide a balance between party autonomy and legal clarity.

Summary Disposal in Arbitration

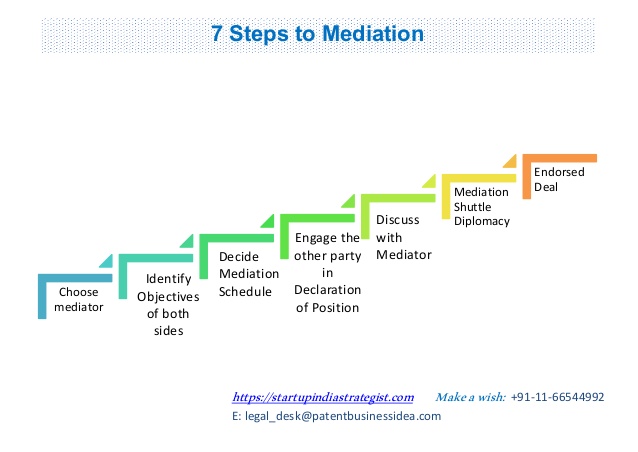

The concept of summary disposal—a mechanism analogous to summary judgment in court proceedings—has been a topic of contemplation. Unlike court proceedings, the Arbitration Act 1996 does not explicitly provide for summary disposal. Still, arbitrators are believed to possess an implicit power for such actions.

Recommendation

The Arbitration Act 1996 should be amended to expressly permit arbitral tribunals, with the parties' agreement, to issue awards on a summary basis. This approach aims to enhance efficiency in dispute resolution while preserving party autonomy. The proposed procedure emphasizes consultation with parties and ensures summary disposal is utilized judiciously.

Court Powers in Support of Arbitral Proceedings

Within the intricate framework of arbitration law, Section 44 of the Arbitration Act 1996 holds sway, empowering courts to issue orders bolstering arbitral proceedings. However, scrutiny reveals nuances warranting refinement.

A central concern revolves around the ambiguity of whether Section 44 court orders can extend to third parties. To align with established case law, a suggested amendment seeks explicit confirmation that such orders are not confined to arbitral entities but can reach third parties when needed.

The debate extends to the restricted right of appeal under Section 44, deemed suitable for arbitral parties but prompting a call for the retention of customary appeal rights for third parties.

Examining Section 44(2)(a), the report contemplates potential legislative tweaks for clarity in witness evidence procedures, though specific reforms are presently withheld.

Emergency Arbitrators

Emergency Arbitrators, appointed for swift resolution of interim matters before the full tribunal's formation, introduce distinct challenges and considerations.

The report swiftly dismisses the notion of a court-administered system for emergency arbitrators, asserting the primacy of parties' agreed-upon rules. It underscores the existing review mechanism, wherein decisions of emergency arbitrators can be scrutinized by the full tribunal.

A noteworthy proposal surfaces regarding the enforcement of emergency arbitrators' orders. The report contemplates two options: a parallel scheme akin to that for regular arbitrators and the utilization of section 44. The recommendation leans towards offering both options, providing flexibility and aligning with practices for regular arbitrators.

Conclusion

In essence, the report serves as a legal compass, urging thoughtful exploration toward a more precisely defined arbitration landscape. As arbitration continues to evolve, maintaining a delicate balance between tradition and adaptation is essential. The recommended reforms seek to enhance transparency, uphold integrity, streamline processes, and address scenarios of removal and resignation, reflecting the dynamic nature of arbitration in the contemporary legal landscape. Whether preserving confidentiality, ensuring arbitrator independence, or refining jurisdictional challenges, these proposals aim to fortify arbitration's position as a reliable dispute resolution mechanism in a rapidly changing world.

[1] Nick Kneall KC: Reforming the Arbitration Act 1996 - Bar Council comment (6 September 2023) Press Release

[2] Review of the Arbitration Act 1996 - Law Commission: Final Report and Bill (5 September 2023)

[3] Sections 33 & 34, Arbitration Act 1996

[4] Halliburton Company v. Chubb Bermuda Insurance Ltd (2020) UKSC 48

[5] Enka v. Chubb (2020) UKSC 38

- The article explores the proposed reforms to the UK's Arbitration Act 1996.

- There is a recommendation for a default rule when determining the governing law.

- There is a recommendation to codify the duty of arbitrators, requiring them to disclose potential bias.