Latest News

Navigating International Arbitration in China: Balancing Legal Constraints and Economic Imperatives

Navigating International Arbitration in China: Balancing Legal Constraints and Economic Imperatives

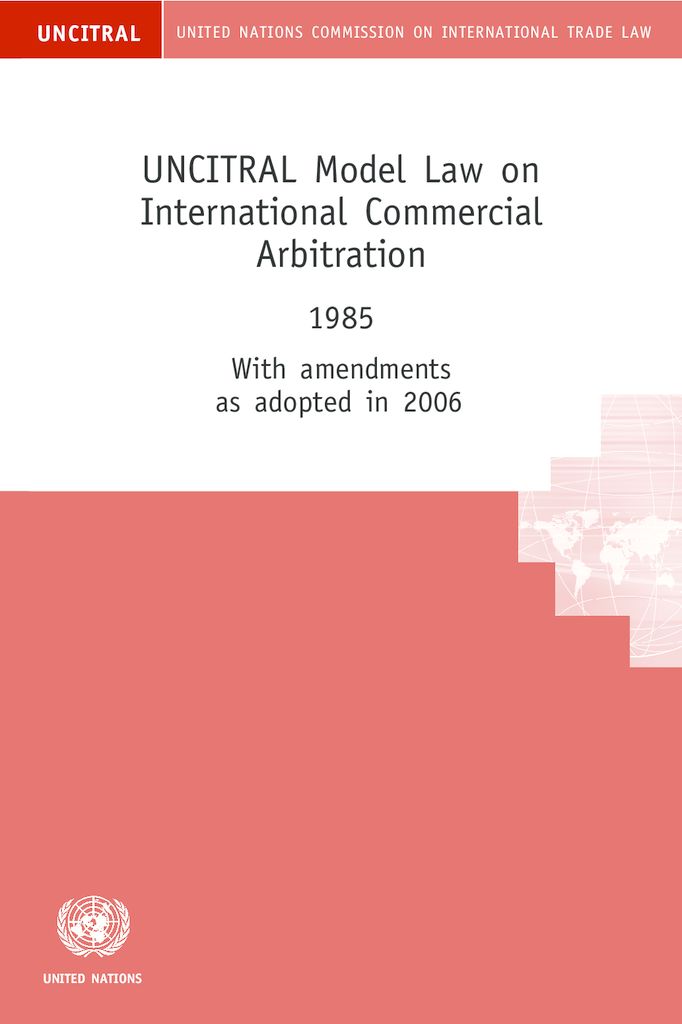

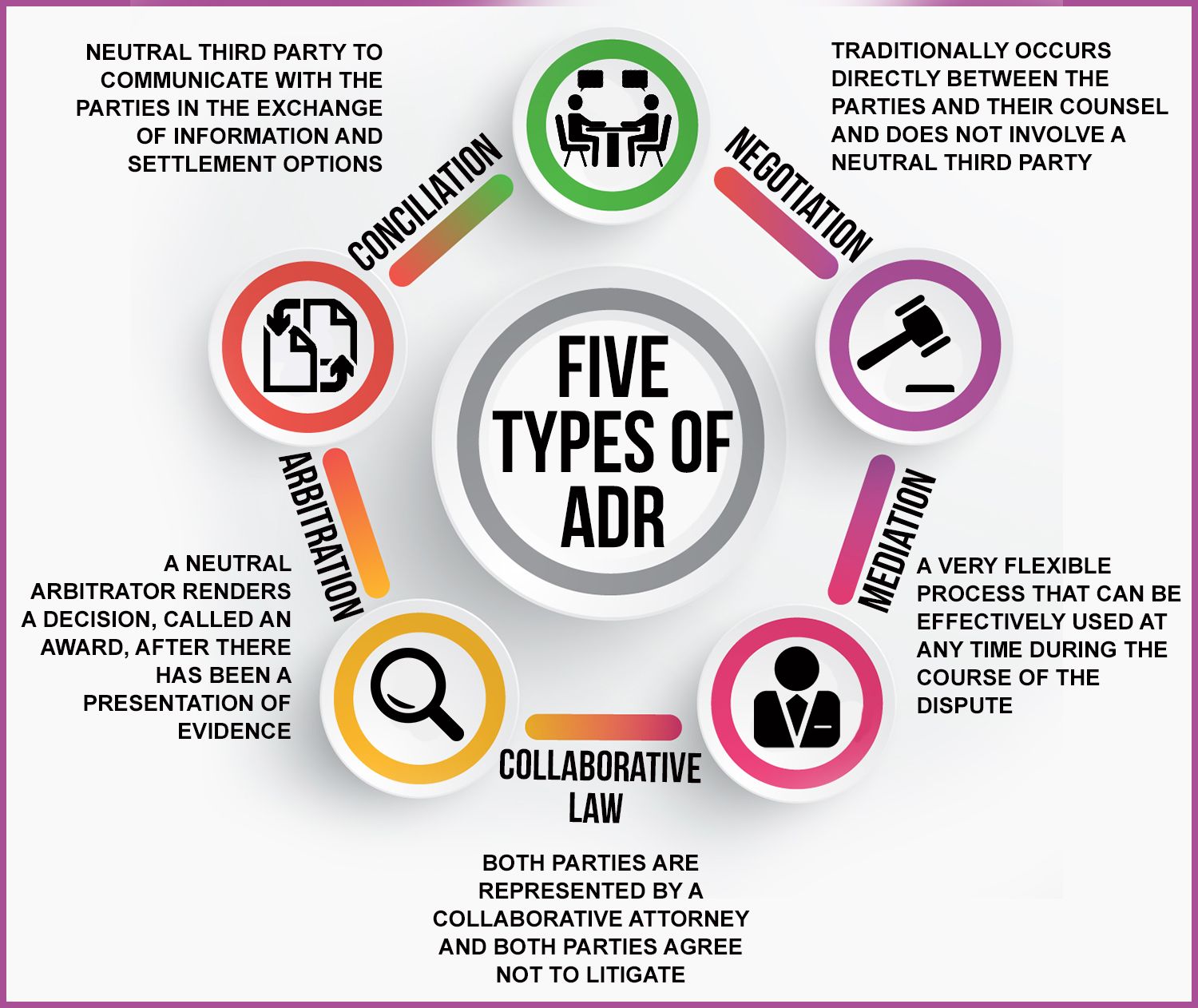

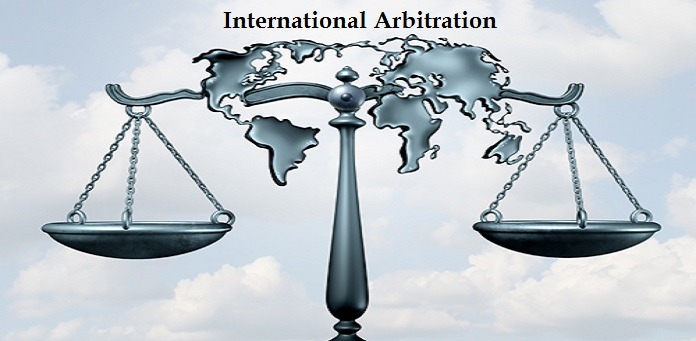

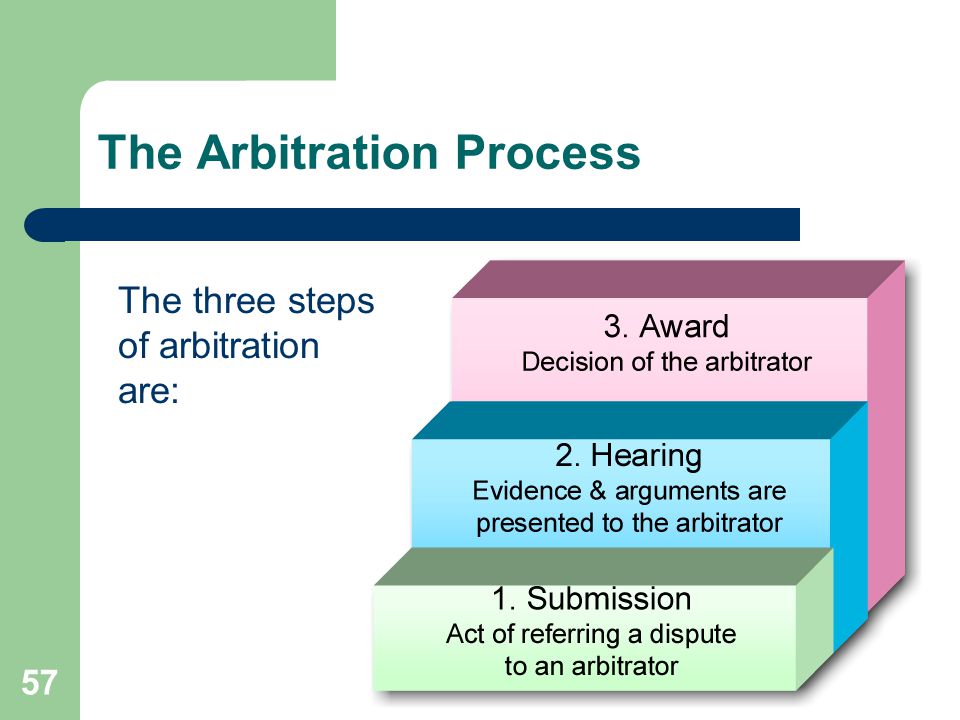

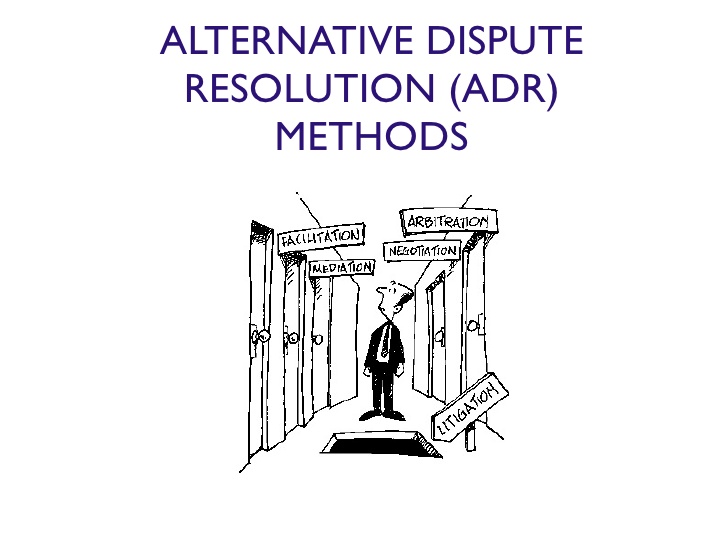

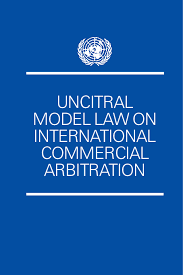

International commercial conflicts are now commonly resolved through arbitration, a procedure that bridges the gap between politics and business. Arbitration is a popular option for international investors and Chinese businesses in China because of the country's investment-driven economy and legal system. Nonetheless, the restrictions that afflict China's legal system also apply to arbitration in that country's developing market. This essay discusses this contradiction and gives a general review of the benefits and drawbacks of international arbitration in China. The article concludes that arbitration can only offer a partial remedy to China's legal system after discussing the economic, social, and cultural reasons why arbitration is popular among foreign investors and Chinese citizens. Due to its apparent benefits, arbitration has emerged as the go-to process for settling disputes involving international commerce. Examines arbitration in China within the framework of globalization and contrasts Chinese customs with international norms, such as the New York Convention and the Model Law on International Commercial Arbitration of the United Nations Committee on International Trade Law (UNCITRAL). Additionally, she draws comparisons between Chinese arbitration and French, Swiss, and English, and her observations from her position as Deputy Counsel at the International Court of Arbitration (ICC Court) of the International Chamber of Commerce.

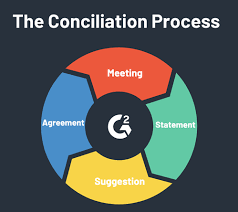

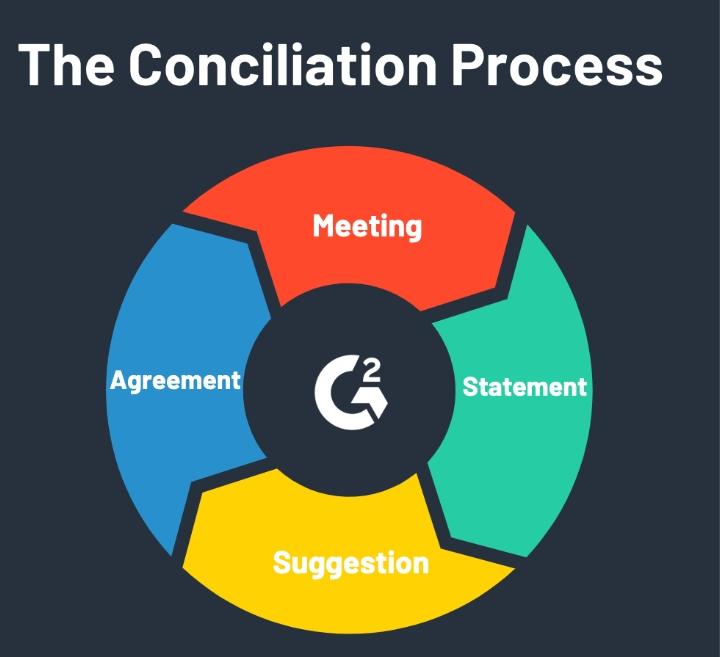

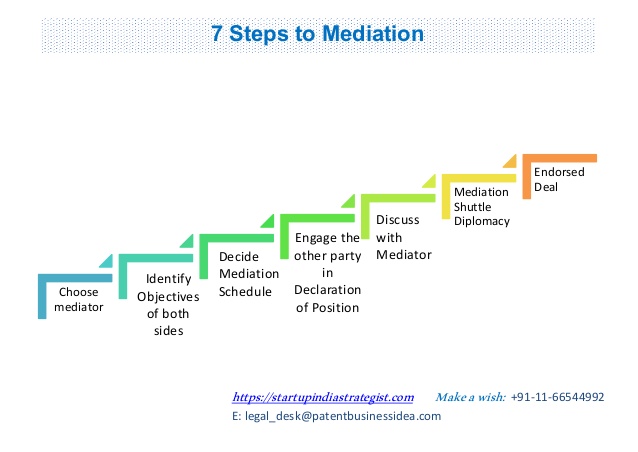

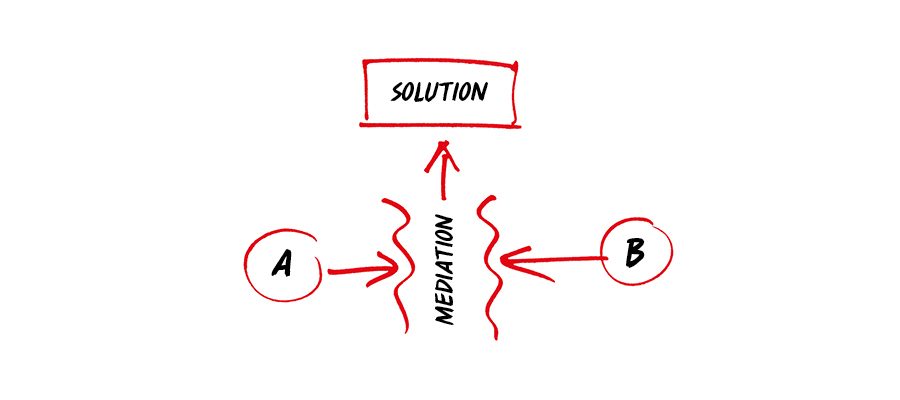

The demands and expectations of those who use international arbitration are reflected in the dynamic nature of transnational arbitration. In an attempt to grow its economy and draw in foreign investment, China has been implementing international arbitration procedures, especially after joining the World Trade Organisation (WTO). Dr. Fan talks about the unique features of Chinese arbitration rules and procedures. This examines the idea of "arb-med"—where the same individual serves as both the arbitrator and the mediator in the same proceeding—drawing comparisons between mediation and arbitration in Chinese and Western settings. Because conflicts arise increasingly frequently as foreign commerce expands, arbitration in China is still heavily reliant on China's domestic courts and legal system. This article examines the idea of "arb-med"—where the same individual serves as both the arbitrator and the mediator in the same proceeding—drawing comparisons between mediation and arbitration in Chinese and Western settings. Because conflicts arise increasingly frequently as foreign commerce expands, arbitration in China is still heavily reliant on China's domestic courts and legal system.

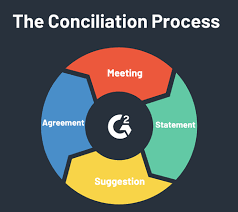

Mediation is a long-standing practice in China that has its roots in Confucianism. To settle disagreements amongst individuals, neighbours, family members, friends, and elders employed this method, which puts morality above the law. The prevalence of mediation in China did not change with the People's Republic of China's establishment in 1949. China's 1954 Provisional General Rules for the Organisation of People's Mediation Committees, on the other hand, formalized the informal mediation system. China's mediation program surpassed all other global dispute settlement programs in size in 1987. The 1989 Rules granted more independence from the Chinese political party while reiterating the government's support for this out-of-court conflict resolution mechanism. China's contemporary mediation system is more autonomous, competent, and effective. People's Mediation Committees can be formed at bigger workplaces and by any Urban Neighbourhood or Village Resident Committee. Although enforcement of the 1989 Rules is not required, contesting parties are generally required to respect the dispute settlement agreement agreed at a mediation. The Chinese codified mediation system has played a significant role in extrajudicial matters.

The commercial history of China is examined in this chapter, with particular attention paid to the interconnected marketplaces found within eight macroregions and the concept of a quadripartite social order, in which merchants are ranked lowest. The author talks about the distinctive arbitration and mediation practices used in China, which were implemented in the absence of a European-style commercial legal framework. The impact of modernization on China's legal system and the evolution of commercial law since 1978 are examined. It is noted that while all three levels compete for resources and authority, the national government wants to transfer more control to the province and local levels. The author also addresses how China's legal culture may influence the development of international arbitration as well as how China is adjusting to international norms through institutional and legislative changes. In the book, China is compared to specific European laws and global norms, along with a few incidents from other Asian nations. Dr. Fan predicts that international arbitration will become a global convergence in the future, offering an optimistic view of transnational arbitration as an organism that is always evolving and free from state control.

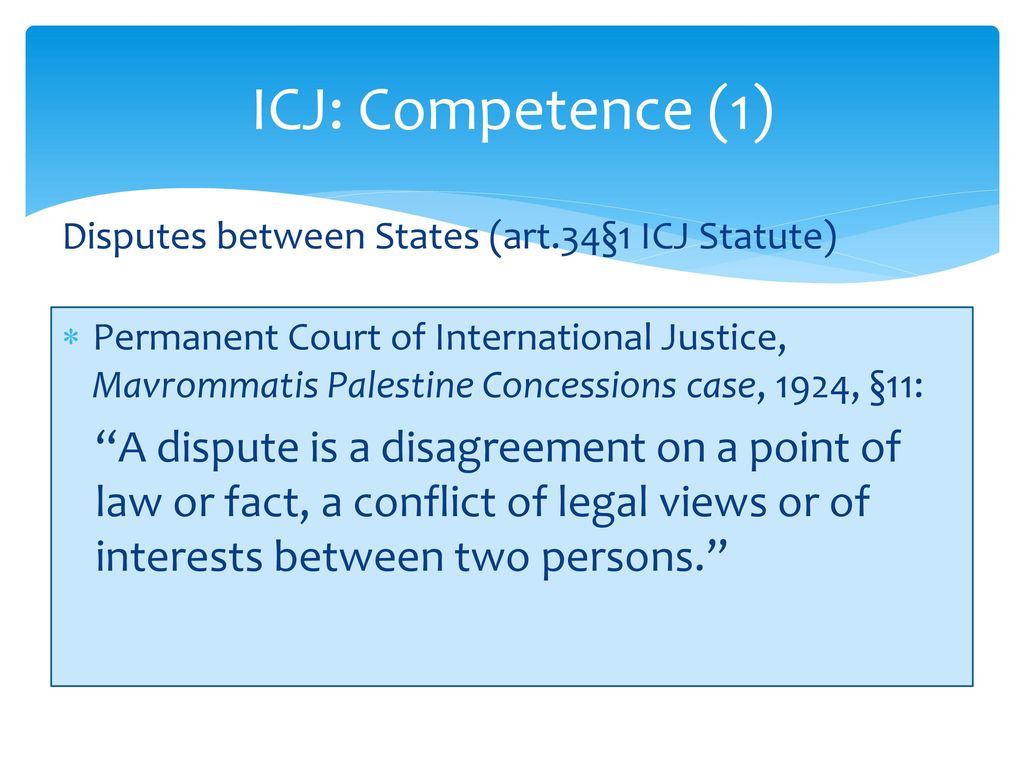

The legal and cultural aspects of arbitration in China. Because arbitration offers certainty, predictability, and impartiality, investors may make well-informed judgments regarding prospective returns in proportion to related risks, which is why it is so popular in China. The "rule of law" is still in its infancy in China and is sometimes subjugated by regional prejudices and interests. An option is arbitration, which gives parties from two separate nations influence over the resolution of their dispute. Local prejudices that may affect proceedings in hostile jurisdictions can be eliminated by allowing parties to select the arbitration's language, location, and arbitrators' nationality or credentials. Additionally, they can bypass a nation's deficient commercial law, which might not offer the dependability that investors need, by selecting the relevant substantive legislation. The confidentiality of most arbitration procedures helps parties to somewhat protect themselves from perceived and actual local prejudices in national courts. Because arbitration is essentially a private dispute settlement process and cannot operate entirely independently of national judicial systems, its dependability is limited. A counter-example to examine how and when national courts and domestic legal systems impact arbitration is the petroleum arbitrations involving Libya. Apart from the official roles played by national courts and legal systems, the location of arbitration also has an informal impact. The local legal community frequently produces arbitrators and legal advisors, and the legal system in which they were taught and schooled has influenced their professional views.

The United States and foreign investors are exerting influence on the stability and dependability of international arbitration in China. Investors are likely to remain cautious participants in the project even while the Chinese government recognizes the need to strengthen its protections for foreign capital to attract investments. In this endeavour, arbitration is essential because it provides a platform for discussion regarding the type and scope of safeguards for foreign investments in China between the Chinese government, Chinese companies, and foreign investors. Investors will be paying close attention to the advancement of arbitration as they increasingly see their investments as profitable ventures. In China, extrajudicial conflict resolution procedures like mediation are commonplace. As long as the Arbitration Law and CIETAC regulations are upheld, China's domestic and international arbitration organizations will continue to be the largest in the world regarding the volume of cases they handle. China's internal and international dispute resolution processes will increasingly rely on the Civil Procedure Law and conflict settlement provisions.

References

[1] Brown, Frederick, and Catherine A. Rogers. "The role of arbitration in resolving transnational disputes: a survey of trends in the People's Republic of China." Berkeley J. Int'l L. 15 (1997): 329.

[2] Harer, Charles Kenworthey. "Arbitration Fails to Reduce Foreign Investors' Risk in China." Pac. Rim. L. & Pol'y J. 8 (1999): 393.

[3] DeVido, Elisa A. "Arbitration in China: A Legal and Cultural Analysis." (2014): 161.

[4] Shen, Christopher. "International Arbitration and Enforcement in China: Historical Perspectives and Current Trends." Currents: Int'l Trade LJ 14 (2005): 69.

[5] Ge, Jun. "Mediation, Arbitration and Litigation: Dispute Resolution in the People's Republic of China." UCLA Pac. Basin LJ 15 (1996): 122.

- China's arbitration system faces challenges due to constraints within the country's legal framework.

- International arbitration is increasingly vital for foreign investors navigating China's investment-driven economy.

- The integration of mediation practices rooted in Chinese culture alongside international arbitration procedures presents unique opportunities and challenges.