Latest News

ADR Mechanisms under the Civil Procedure Code

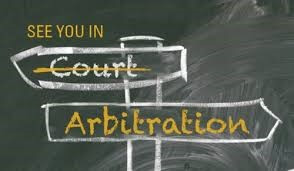

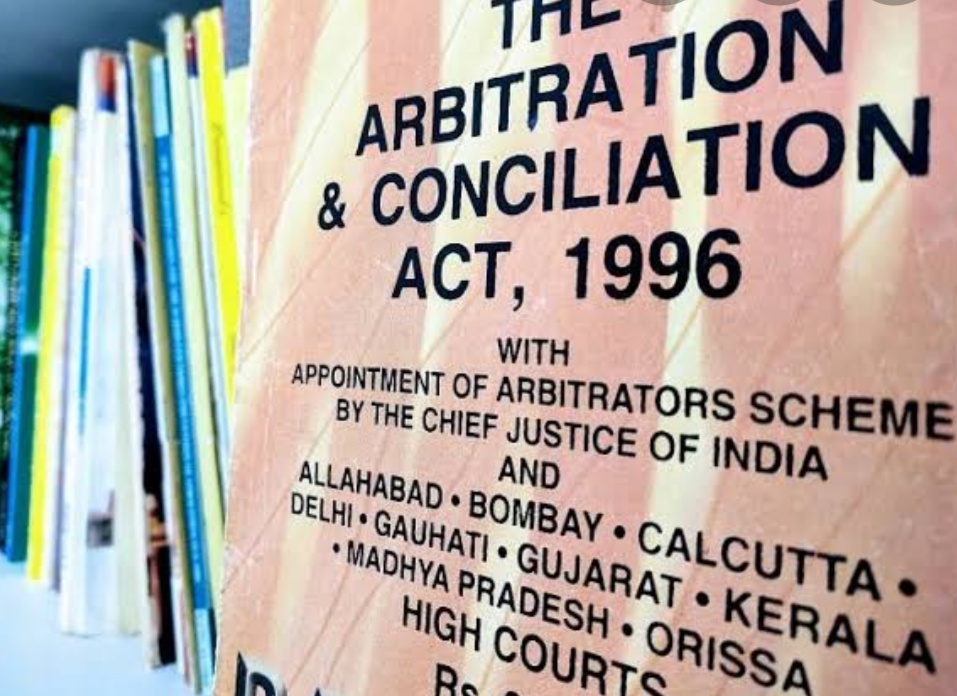

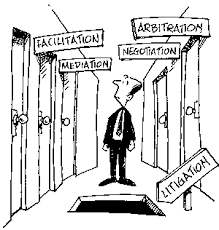

An increase in cross-border trade in goods, services, technology and flows of investment, people and information has created a growing interdependence of the world’s economies, cultures and populations. Fueled by globalization, this interaction between people on an international level has led to the formation of business contracts and partnerships between companies and individuals not residing in the same location. With inter-country disputes that are private in nature and do not involve governments, there is no set jurisdiction for courts, so this is where Alternate Dispute Resolution (ADR) comes into play[1]. The principles of Alternate Dispute Resolution allow certain freedom to parties which enables them to choose the location, time and the procedural rules that will apply to them. However, so far in India, only arbitration has been standardized and institutionalized due to pressure from international forces like the United Nations Commission on International Trade Law (UNCITRAL) Model Law on International Commercial Arbitration and countries with established systems of arbitration like Singapore and Hong Kong. The rules for Arbitration and Conciliation have been extensively provided for in the Arbitration and Conciliation Act, 1996 which has been reformed twice since its enactment to keep up with the demands of legal evolution[2]. The other methods of Alternate Dispute Resolution – mediation, judicial settlement and Lok Adalats, have, however, not been institutionalized yet and find themselves provided for under Section 89 of the Civil Procedure Code (CPC). Section 89 of the Civil Procedure Code seeks to reduce the burden of cases on the courts by providing for mandatory mediation, arbitration, conciliation, judicial settlement or Lok Adalat for an attempted settlement, on the failure of which, the cases will be tried by a court of competent jurisdiction.

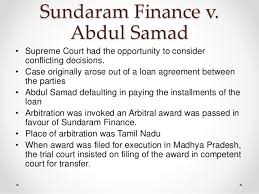

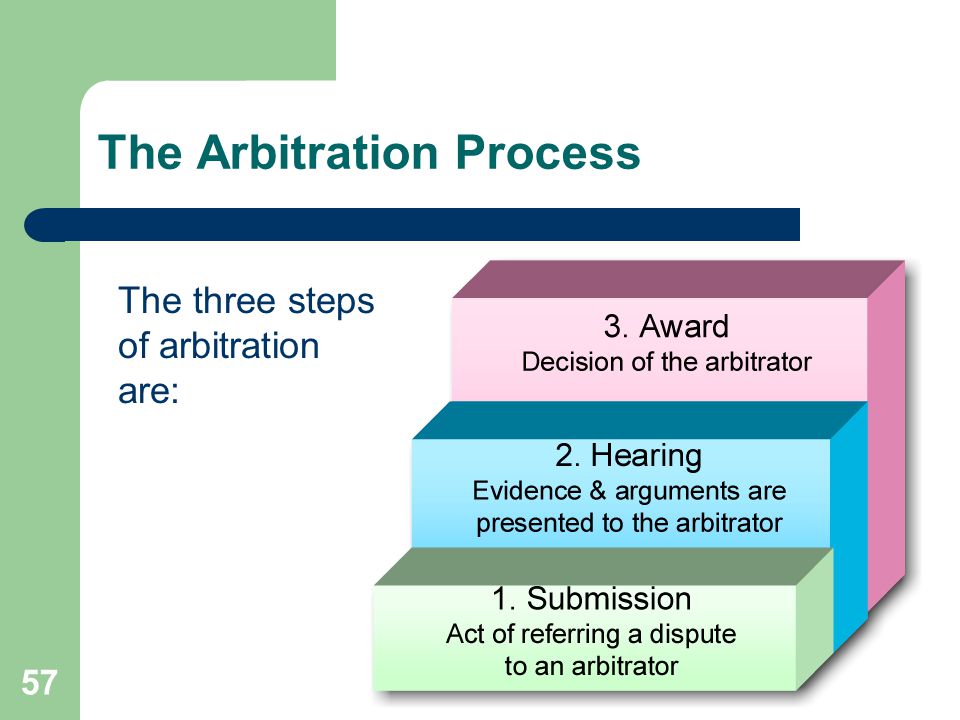

Arbitration is an adjudicatory process of alternate dispute resolution governed by rules laid down in the Arbitration and Conciliation Act, 1996. The process, unlike other forms of ADR, is adjudicatory because the arbitrator acts in the same capacity as a judge whereby, after hearing the arguments put forth by both parties and analyzing the evidence, he proclaims an award[3]. An award is much like a judicial decision and it is binding on the parties, enforceable by courts and final in nature, which means that an arbitral award cannot be appealed or questioned[4]. The court, if it so feels that a case is more suitable to be settled by arbitration, can mandate the parties to proceed with arbitration. Earlier this provision under Section 89 of the CPC was enforceable even if the parties did not have an existing arbitration agreement but after the Afcons Infrastructure Ltd. and Anr. v. Cherian Varkey Construction Co. (P) Ltd.[5] case, the courts now require an arbitration agreement or consent of the parties before referring a case to arbitration proceedings.

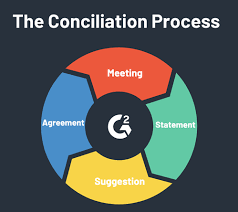

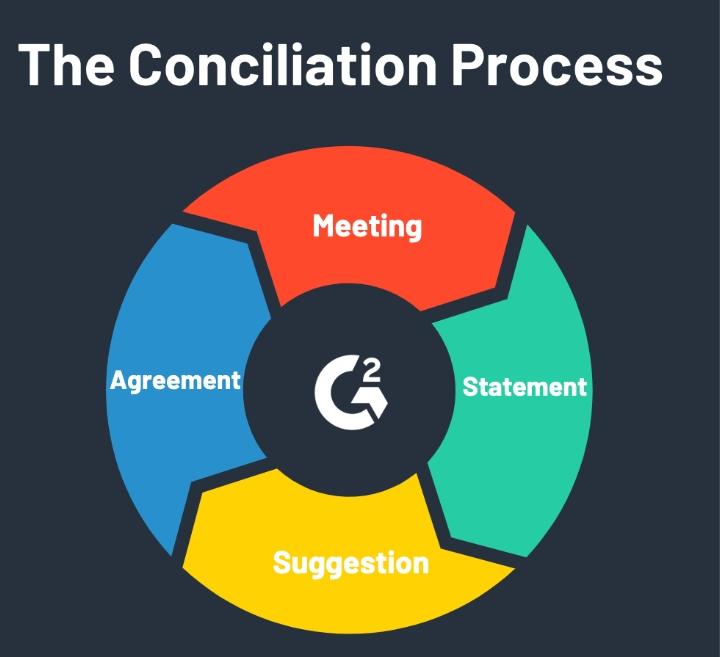

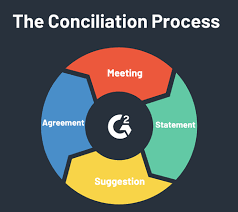

Conciliation is also governed by the Arbitration and Conciliation Act, 1996 but it is not an adjudicatory process. If the court, while considering the facts and nature of the case, finds that it is possible for the parties to arrive at a settlement, the matter ca be referred to conciliation if both parties consent to it. Conciliation is a process by which parties, which the help of a neutral third party known as a conciliator, negotiate and come to an agreement which both of them agree to[6]. The terms of the settlement have the same enforceability as an arbitral award but a dispute if not resolved by conciliation can be returned to the court for a trial.

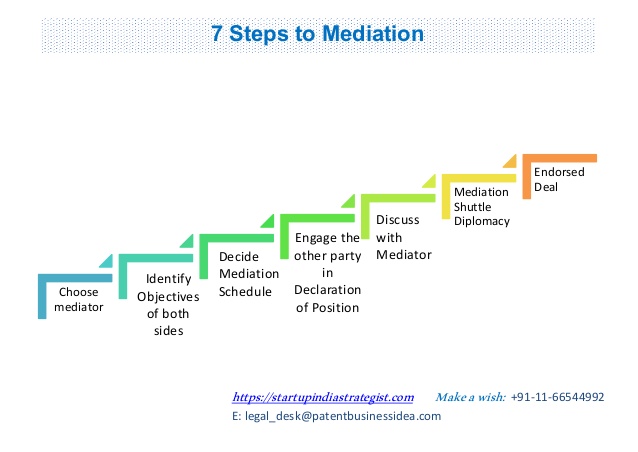

Mediation is a non-formal but structures process of alternate dispute resolution wherein a neutral third party known as a mediator facilitates an honest conversation between parties which allows them to discuss their needs and arrive at a compromise which mutually benefits both parties[7]. The mediator does not have the power to pronounce an award like an arbitrator does, as he is only a mere facilitator who can suggest options and creative ideas that might help resolve the dispute between parties. Since mediation adopts a cooperative approach, allowing parties to communicate and work with each other, it is often used to resolve cases involving property, partition, marriage, divorce, custody and business, where the relationship between parties must be preserved beyond the dispute[8]. Once the dispute has bene mediated and a settlement has been reached, it is sent to the court for enforcement.

Judicial Settlements are used when a judge feels like the case as potential to be settled without litigation or trial but with merely some help and guidance. The judge or judicial officer in charge of settling the case will have to make the necessary efforts needed to help the parties reach a settlement and in doing so he must follow the rules and procedure that may be prescribed.

Lok Adalat literally translates to “people’s court” and it is a method of alternate dispute resolution that has long been in existence. Under Section 89 of the CPC, when the court is satisfied that the facts of the case and the issues at hand are not of a complicated nature and that parties might be open to a settlement, the matter is referred to a Lok Adalat. A Lok Adalat does not have any judicial or adjudicatory functions and merely facilitates a compromise between parties according to the rules prescribed by the Legal Service Authority Act, 1987. The Lok Adalat is guided by principles of justice, fairness and equity and keeping these principles in mind, it must discuss the case with the parties and try to come to an agreement, but if this is unsuccessful the matter will be referred to the court for resolution[9].

While the methods of ADR, barring arbitration, seem alike, the court will consider the facts of the case and refer the matter to any of the ADR processes based on the suitability of the subject matter to the process. Another difference is that unlike arbitration and conciliation where the consent of the parties is necessary for referral to ADR, the court can, if satisfied, refer the dispute to Lok Adalat, mediation or judicial settlement even without the consent of the parties.

[1] Bijoylashmi Das, Commercial Arbitration in India – An Update, Mondaq, (Jan. 6, 2014, 1:12 PM), https://www.mondaq.com/india/arbitration-dispute-resolution/284570/commercial-arbitration-in-india--an-update.

[2] Abhishek Bhargava, Salient Features of Arbitration and Conciliation Act, 1966, India Institute of Legal Science, (Apr. 11, 2020, 3:09 PM), https://www.iilsindia.com/blogs/salient-features-of-arbitration-and-conciliation-act-1996/.

[3] Editor, Alternative Dispute Resolution under Section 89 of the Code of Civil Procedure, Shodhganga, (Aug. 10, 2013, 8:48 PM), https://shodhganga.inflibnet.ac.in/bitstream/10603/26666/12/12_chapter%206.pdf.

[4] Anubhav Pandey, All you need to know about Alternative Dispute Resolution (ADR), iPleaders, (May 9, 2017, 11:37 AM), https://blog.ipleaders.in/adr-alternative-dispute-resolution/.

[5] Afcons Infrastructure Ltd. and Anr. v. Cherian Varkey Construction Co. (P) Ltd, (2010) 8 SCC 24

[6] Editor, Forms of Alternative Dispute Resolution, MillerLaw, (Mar. 17, 2020, 3:44 PM), https://millerlawpc.com/alternative-dispute-resolution/.

[7] Editor, What is Alternative Dispute Resolution?, FindLaw, (Jun. 20, 2016, 4:56 PM), https://hirealawyer.findlaw.com/choosing-the-right-lawyer/alternative-dispute-resolution.html.

[8] Gaurav Prakash, Section 89 of CPC – A Critical Analysis, LegalServiceIndia, (Sep. 23, 2012, 5:19 PM), http://www.legalserviceindia.com/legal/article-385-section-89-of-cpc-a-critical-analysis.html.

[9] Justice S. U. Khan, Judicial Settlement under Section 89 C.P.C., IJTR, (Aug. 28, 2016, 7:46 PM), http://ijtr.nic.in/Article_chairman%20S.89.pdf.

- Alternate Dispute Resolution

- Civil Procedure Code

- India