Latest News

Illegally Obtained Evidence: Shaping Perspectives on Admissibility in Arbitration

Introduction

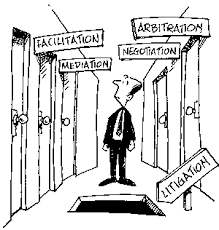

International arbitration relies heavily on factual evidence, a cornerstone in dispute resolution. The realm of evidence, a linchpin in legal proceedings, confronts a contentious debate surrounding the admissibility of unlawfully obtained evidence. This article explores the multifaceted landscape of this issue, delving into the rules governing evidence in international arbitration, approaches taken by arbitral tribunals, and the potential impact on the enforceability of awards.

Evidence in International Arbitration: A Fundamental Aspect

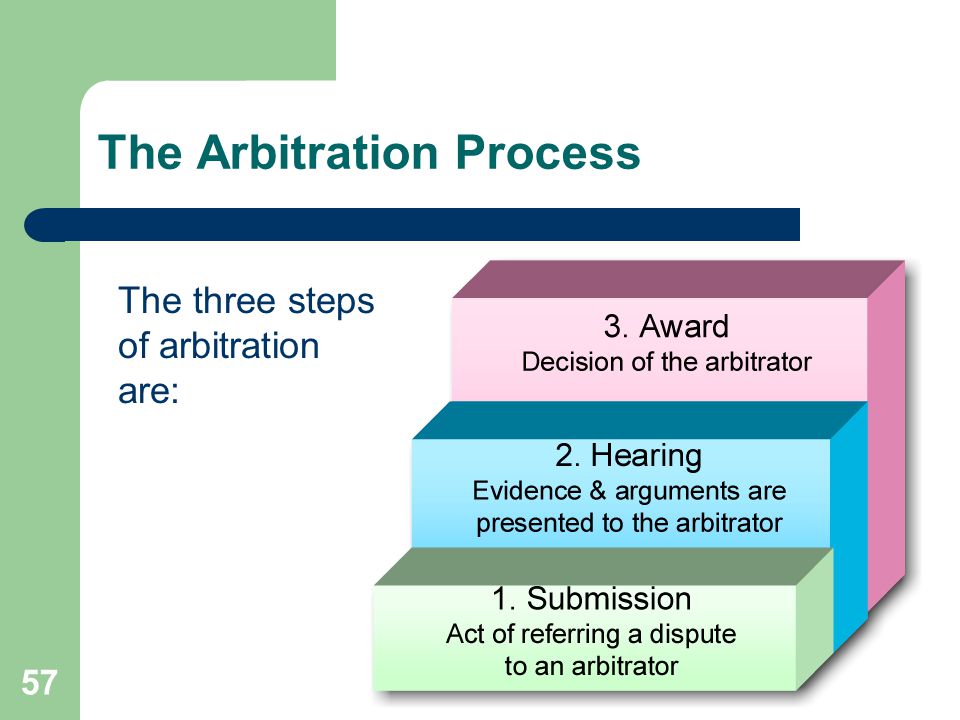

In any adjudication procedure, evidence plays a pivotal role in establishing the credibility of a party's submission. Illegally obtained evidence emerges when procured in violation of the law, presenting myriad legal, moral, and ethical quandaries. In the realm of arbitration, where the procedural landscape lacks a specific legal framework, the admissibility of evidence is not dictated by stringent laws but rather by a combination of pre-agreed institutional or contractual rules and a procedural order issued post-initiation.

Various arbitral institutions, such as the Singapore International Arbitration Centre (SIAC), the London Court of International Arbitration (LCIA), and the Mumbai Centre for International Arbitration (MCIA) provide tribunals with considerable discretion in determining the admissibility, relevance, and materiality of evidence.

- UNCITRAL Arbitration Rules, 2010 (Article 27(4)): Empowers the tribunal to "determine the admissibility relevance, materiality, and weight of the evidence offered."

- SIAC Arbitration Rules, 2016 (Rule 19.2): States that the tribunal "shall determine the relevance, materiality, and admissibility of all evidence," with no requirement to adhere to the rules of evidence of any applicable law.

- LCIA Rules, 2020 (Rule 22.1(vi)): Grants tribunals the freedom "to decide whether or not to apply any strict rules of evidence (or any other rules) as to the admissibility, relevance or weight of any material tendered by a party on any issue of fact or expert opinion."

- MCIA Rules, 2016 (Rule 25.1): Vests within the tribunal the power to determine the “admissibility, relevance, materiality, and weight of any evidence, including whether to apply strict rules of evidence or not. The tribunal shall not be bound to apply any rules of evidence.”

Unlike domestic proceedings, international arbitration lacks a uniform set of rules leading to a diverse range of approaches to handling evidentiary matters. The International Bar Council (IBA) Rules on the Taking of Evidence in International Arbitration offer guidance, stating that "the taking of evidence shall be conducted on the principles that each Party shall act in good faith".[1]

The arbitral tribunal may exclude illegally obtained evidence upon request or its motion.[2] Despite this freedom, the lack of a clear consensus on the issue has led to divergent approaches among arbitral tribunals. Factors such as the involvement of the party offering the evidence in the illegality, proportionality, materiality, and the severity of the illegality have been considered in past decisions to navigate a nuanced path.

Balancing Act: Approaches to Illegally Obtained Evidence

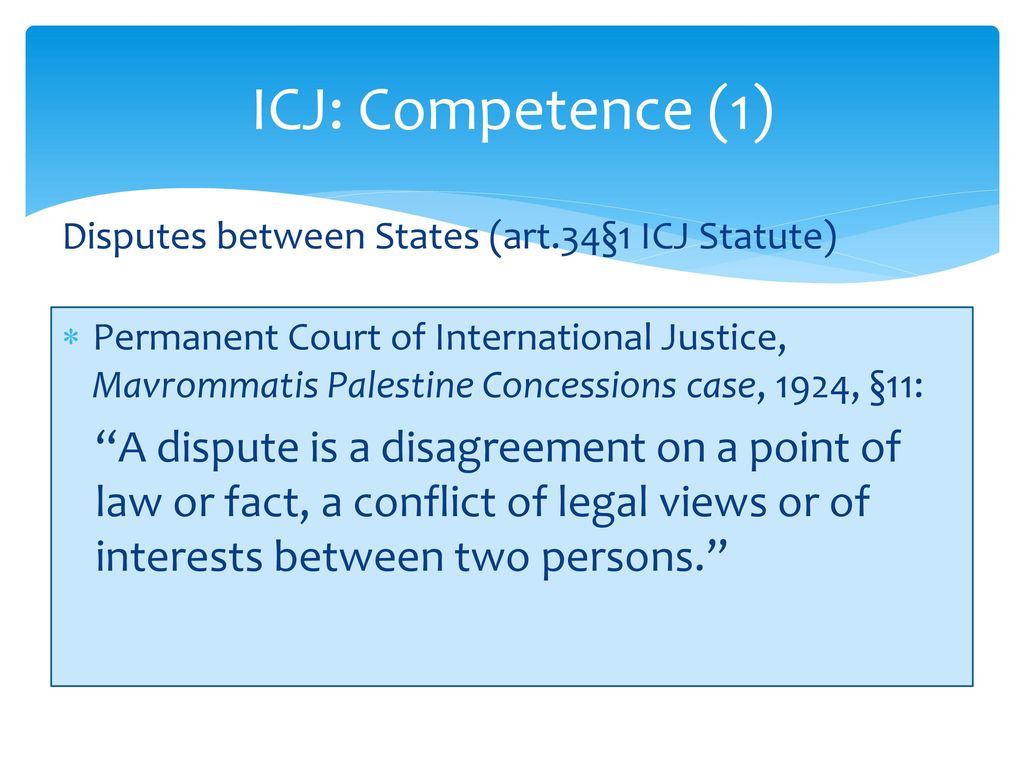

Arbitral tribunals faced with the admissibility of illegally obtained evidence engage in a delicate balancing exercise. Precedents such as the Corfu Channel case showcase instances where evidence obtained against a state's sovereignty was deemed admissible.[3] Conversely, cases like United States Diplomatic and Consular Staff in Tehran[4] demonstrate a reluctance to admit evidence obtained in violation of international conventions.

In the case of Caratube v. Kazakhstan,[5] the claimant sought to submit eleven documents that had become publicly accessible on the Internet due to a hacking incident involving the Kazakhstan government's IT system. The hackers had disseminated around 60,000 documents through a website called "Kazakhleaks." The tribunal, in its ruling, permitted the inclusion of all non-privileged leaked documents. However, it exercised discretion to exclude any illegally leaked privileged documents, emphasizing the need to afford privileged materials the highest level of protection.[6] This decision underscores the tribunal's recognition of the sensitivity surrounding privileged information and its commitment to upholding the integrity of such materials within the arbitral proceedings.

In the legal dispute of Methanex Corp v. USA,[7] the claimant's investigator resorted to 'dumpster diving,' and as a consequence, the files of its competitors were unlawfully appropriated. The tribunal, in its judgment, deemed this evidence as obtained through multiple acts of trespass over an extended period. Recognizing the gravity of these actions, the tribunal concluded that admitting such evidence would contravene a general duty of good faith outlined in the UNCITRAL Rules. This duty is considered essential for the proper functioning of international arbitration and is incumbent upon all participants in such proceedings.[8]

The tribunal further emphasized that both parties held a duty "to conduct themselves in good faith during these arbitration proceedings and to respect the equality of arms between them." The principles of 'equal treatment' and procedural fairness, as mandated by Article 15(1) of the UNCITRAL Rules, were underscored as integral to the arbitration process. Consequently, as a result of these considerations, the tribunal exercised its authority to refuse the inclusion of the contested documents as evidence. This decision reflects the tribunal's commitment to maintaining the integrity of the arbitration proceedings, ensuring fairness, and upholding the principles of equal treatment and good faith among the involved parties.

Decisions in cases like Methanex Corp v USA and Libanaco Holdings v Turkey further underscore the lack of a standardized approach. While Methanex Corp held that evidence obtained through trespass was inadmissible, Libanaco Holdings addressed the destruction of intercepted communications in response to surveillance.[9]

In the Context of Indian Arbitration

The matter at hand revolves not around the relevance of illegally obtained evidence but, rather, its admissibility within the framework of the Indian judiciary. The Tenth Law Commission of India, in 1983, presented a report shedding light on this issue, which forms the basis of our exploration.[10] The report aptly highlighted the central issue, emphasizing that the absence of a specific statutory or constitutional provision to exclude particular types of evidence renders the fact of illegal acquisition inconsequential regarding its admission at a criminal trial.

The Report classified countries into four categories based on their approaches to illegally obtained evidence:

- First category countries: Admit such evidence as there is no law excluding it due to illegal procurement.

- Second category countries: Acknowledge the relevance of evidence procured through illegal or improper means but retain the right to reject it.

- Third-category countries: Have specific statutory provisions excluding illegally obtained evidence.

- Fourth category countries: Exclude illegally obtained evidence through constitutional guarantees or judicial constructions of such guarantees.

The report classified India into the first category. The legal stance on the admissibility of illegally obtained evidence in the Indian judiciary is elucidated through numerous case laws. Despite its admissibility, police officers or individuals procuring evidence illegally may face compensation as a form of punishment. The Report proposed the inclusion of Section 166A into the Indian Evidence Act, granting courts the authority to refuse admission to illegally obtained evidence if its acquisition would disrupt the administration of justice. However, this section was never incorporated, and the jurisprudence on the admissibility of such evidence continues to be shaped by case laws.

In the case of Pooran Mal v. Director of Inspection,[11] the Supreme Court declined to issue a writ against the admission of evidence gathered through an illegal search and seizure, citing Section 5 of the Indian Evidence Act, which deems relevancy as the sole test of admissibility. The Court asserted that neither the spirit of the Constitution nor fundamental rights warrant the exclusion of evidence obtained through an illegal search.

Similarly, in R.M. Malkani v. State of Maharashtra,[12] where evidence was collected using a recording device, the Court deemed the illegally obtained evidence admissible, emphasizing that the scrutiny of such evidence serves to caution police officers, fostering proper behaviour.

In Dnyaneshwar v. State of Maharashtra,[13] the court addressed the illegal search of the petitioner's house under the guise of Section 165 CrPC. Despite the illegality, the Court held the evidence admissible, showcasing a willingness to consider evidence obtained from an illegal search if deemed relevant.

The Indian judiciary leans towards admitting illegally obtained evidence, citing the absence of a legal barrier. Despite criticism, the recommended Section 166A to restrict such evidence was not adopted. However, the judiciary, like arbitral tribunals, can invoke fairness principles to deny admissibility. The lack of statutory guidance doesn't preclude courts from a nuanced, case-specific approach, ensuring a fair and just legal.

Impact on Enforceability: Navigating Legal Conundrums

While arbitral tribunals possess the authority to decide on evidence admissibility, their choices can have repercussions on award enforceability. In Germany, for instance, an award based on illegally obtained evidence may be subject to non-recognition if the affected interests outweigh the need for finality. This underscores the importance of a judicious approach to evidence admissibility in international arbitration.[14]

Conclusion

In the absence of a standardized approach, arbitral tribunals must delicately balance the competing interests of parties when addressing the admissibility of illegally obtained evidence. The jurisprudence of the International Court of Justice provides some guidance, but the nuanced nature of each case requires careful consideration. As the international arbitration landscape continues to evolve, finding a harmonized solution to this complex issue remains a challenge, highlighting the intricate interplay between the right to be heard, privacy rights, and the duty of good faith.

References

[1] IBA Rules on the Taking of Evidence in International Arbitration 2020, Preamble.

[2] IBA Rules on the Taking of Evidence in International Arbitration 2020, Article 9.3.

[3] Corfu Channel (United Kingdom of Great Britain and Northern Ireland v. Albania), International Court of Justice, 9 April 1949, p. 36. At Corfu-Channel-case.pdf (acerislaw.com)

[4] United States Diplomatic and Consular Staff in Tehran (United States of America v. Iran) (icj-cij.org)

[5] Caratube v. Kazakhstan, ICSID Case No ARB/08/12. At AN DEN GELBEN STELLEN VON ICSID CARATUBE EINZELHEITEN EINSETZEN: (acerislaw.com)

[6] Edna Sussman, Cyber Intrusion as the Guerrilla Tactic: An Appraisal of Historical Challenges in an Age of Technology and Big Data, 20 EAFIA 849, 853 (2019).

[7] Methanex v USA, Final Award, 3 August 2005, para. 53. At Microsoft Word - AATitlePage.f.wpd (acerislaw.com)

[8] Peter Ashford, The Admissibility of Illegally Obtained Evidence, 85(4) IJAMDM 377, 380 (2019).

[9] Libanaco Holdings v Turkey, ICSID Case No. ARB/06/8, Decision on Preliminary Issues, 23 June 2008, para. 82. At INTERNATIONAL CENTRE FOR SETTLEMENT OF INVESTMENT DISPUTES (acerislaw.com)

[10] Law Commission of India, 94th Report on Evidence Obtained Illegally or Improperly: Proposed Section 166A, Indian Evidence Act, 1872, (1983).

[11] Pooran Mal v. Director of Inspection, [1974] 1 SCC 345.

[12] R.M. Malkani v. State of Maharashtra, 1973 AIR 157.

[13] Dnyaneshwar v. State of Maharashtra, 2019 SCC OnLine Bom 4949.

[14] C. Borris, R. Hennecke, et al., New York Convention, Article V [Grounds for Refusal of Recognition and Enforcement of Arbitral Awards], in R. Wolff (ed), New York Convention: Article-by-Article Commentary (Second Edition) 231, para. 554.

- The article delves into the complex realm of admissibility challenges surrounding unlawfully obtained evidence in international arbitration.

- Highlighting the lack of a uniform approach, it explores how different international arbitral tribunals navigate the admissibility of illegally procured evidence.

- It elucidates the stance of the Indian judiciary on the admissibility of illegally obtained evidence, revealing a nuanced approach shaped by case law rather than statutory provisions.