Latest News

A Comprehensive Analysis of UNCLOS Dispute Resolution Mechanisms

INTRODUCTION:

In the realm of UNCLOS, dispute resolution is a multifaceted landscape encompassing a myriad of mechanisms detailed in its extensive hundred-article framework. Within Part XV of the convention, the intricate architecture of dispute settlement mechanisms takes centre stage, becoming an inherent and non-negotiable aspect of UNCLOS participation for states. Notably, UNCLOS leaves no room for reservations, implying universal consent to its comprehensive regulations. However, a unique flexibility arises as parties retain the autonomy to select the specific procedure applicable to their dispute resolution. This feature distinguishes UNCLOS by allowing tailored approaches within its established framework, creating a dynamic and adaptable environment for addressing maritime disputes. This article aims to delve into the procedural aspects and jurisdiction of these tribunals, shedding light on their roles in resolving disputes related to the marine environment, navigation, pollution, marine scientific research, and fisheries.

PROCEDURES IN PART XV OF UNCLOS:

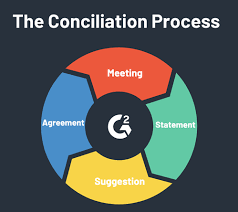

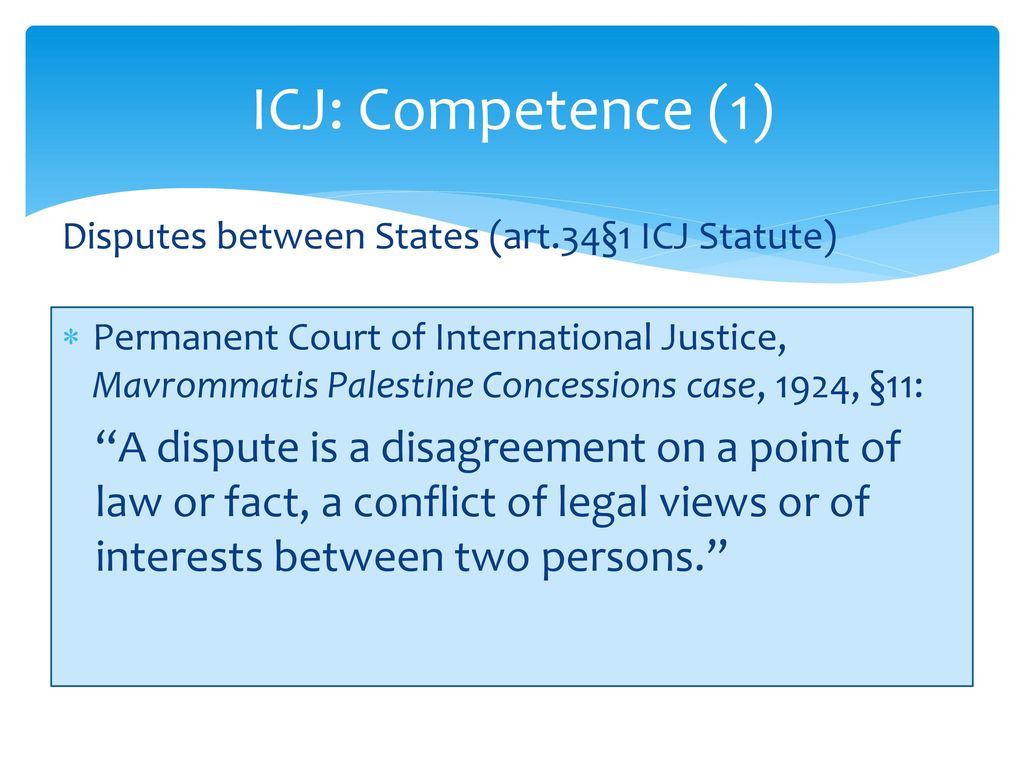

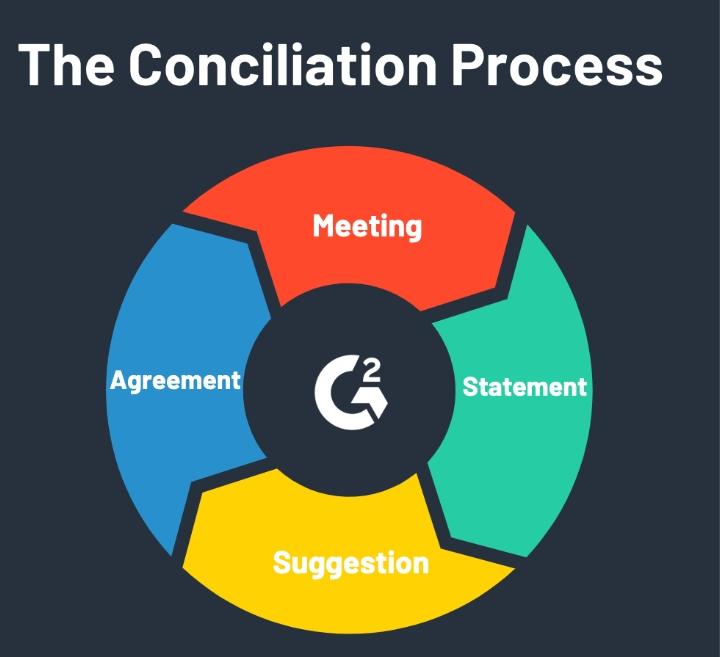

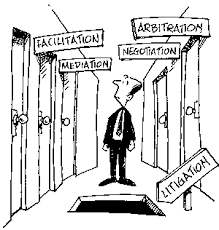

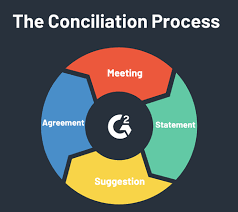

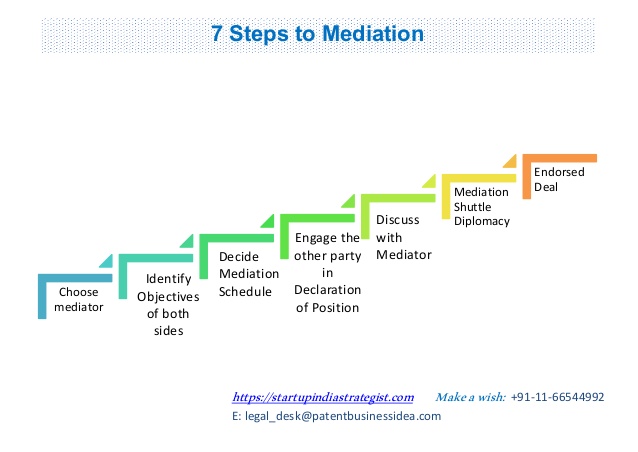

The procedures outlined in Part XV of UNCLOS encompass both voluntary and compulsory mechanisms for dispute resolution. Voluntary procedures, as detailed in Section 1[1], rely on the consent of the parties involved and include traditional methods such as reconciliation, separate agreements, or negotiation. If mutual agreement is absent, parties may opt for voluntary arbitration outside the convention's framework. On the other hand, Section 2[2] introduces compulsory procedures, involving binding third-party settlements through entities like the International Tribunal for the Law of the Sea (ITLOS) and the International Court of Justice (ICJ). This compulsory framework aims to ensure a uniform interpretation of the convention, balancing the interests of both powerful and developing states. However, limitations exist, detailed in Section 3[3], excluding politically charged disputes from compulsory adjudication. States can further opt out of compulsory settlement through written declarations, known as "Optional Declarations" under Article 298[4] of UNCLOS, for specific categories of disputes. The relationship between voluntary and compulsory procedures is interconnected, allowing parties to move from negotiation to compulsory mechanisms if no resolution is reached[5]. Art. 282[6] emphasizes that if parties have prior agreements with binding dispute settlement mechanisms, those procedures take precedence over UNCLOS's compulsory processes. This underscores the significance of negotiations, requiring states to exchange views before resorting to compulsory procedures, reinforcing the importance of dialogue in dispute resolution.

ARBITRATION PROCEDURE IN UNCLOS:

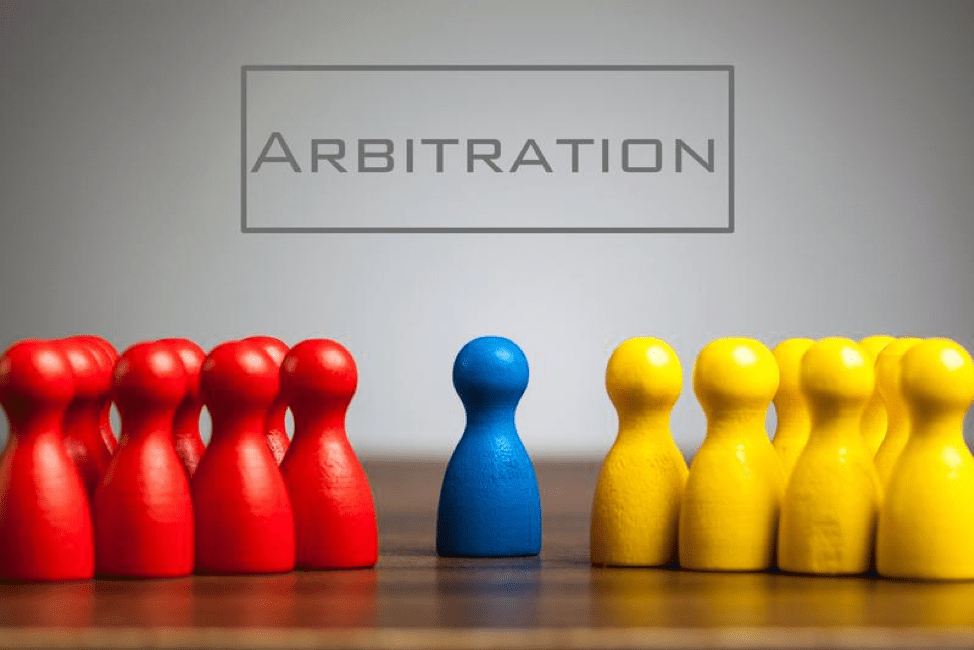

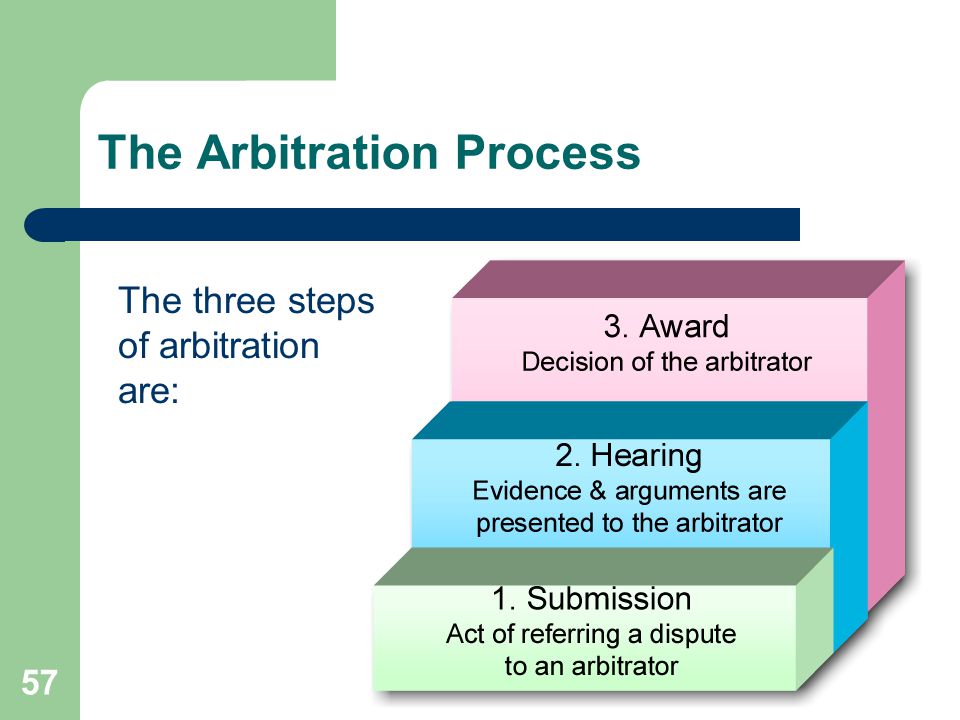

Arbitration under the United Nations Convention on the Law of the Sea (UNCLOS) is a complex and nuanced process, involving two distinct types of tribunals: one established under Annex VII and another under Annex VIII. The special arbitral tribunal, as per Annex VIII[7] of UNCLOS, focuses on technical issues and disputes about the protection and preservation of the marine environment. Comprising experts and specialists in the relevant fields, this tribunal not only adjudicates but also encompasses fact-finding and conciliation. It is worth noting that only a limited number of states, a mere 11, have opted for this mode of arbitration, making it less commonly chosen among state parties. On the other hand, Annex VII[8] provides for the default choice of procedure, making it the preferred option for state parties. In cases where disputing parties either choose different methods for settlement or fail to agree on a method, the dispute automatically falls under the jurisdiction of an arbitral tribunal constituted under Annex VII. The tribunal, composed of five members, with each party appointing one member and three more chosen by mutual agreement, becomes the default mechanism for dispute resolution. In situations where one party refuses to cooperate with the tribunal constitution or mutual agreement on neutral members cannot be reached, a third state is chosen by the parties, or the president of the International Tribunal for the Law of the Sea (ITLOS) steps in for necessary appointments. The procedural rules for arbitration are determined by the tribunal, but parties retain the power to choose rules according to their preferences, maintaining party autonomy in arbitration. Crucially, the tribunal's proceedings continue even if one party fails to appear or present its case. The arbitral award, once delivered, is binding and without appeal. In case of disagreement on the interpretation of the award, parties can submit the matter to the deciding tribunal for further clarification, adhering to the procedures established under Annex VII. To comprehend the jurisdiction of the Arbitral Tribunal under Annex VII, a notable case, "The Southern Bluefin Tuna Arbitration[9]," provides valuable insights. Japan challenged the tribunal's jurisdiction, arguing that the dispute fell under the "Commission for the Conservation of Southern Bluefin Tuna" (CCSBT) and not UNCLOS. Japan contended that the CCSBT allowed parties to resolve disputes through their chosen mechanism, excluding UNCLOS procedures. The tribunal, however, ruled that the dispute was under both CCSBT and UNCLOS, giving parties the freedom to choose their desired mechanism for dispute resolution, as per Article 281 of UNCLOS. The controversial aspect of the tribunal's interpretation was its assertion that CCSBT implicitly excluded any further procedure under Part XV of UNCLOS, despite the absence of an express exclusion in the CCSBT text. This case illustrates the tribunal's use of one treaty's text to infer the exclusion of dispute resolution procedures under another treaty. In summary, the arbitration procedures under UNCLOS, whether under Annex VII or Annex VIII, play a vital role in resolving disputes related to the seas. While Annex VII is the default and more commonly chosen option, Annex VIII, with its focus on technical issues, provides an alternative avenue for specialized disputes. The jurisdiction and procedural aspects, as demonstrated by "The Southern Bluefin Tuna Arbitration," highlight the intricate nature of resolving disputes under UNCLOS.

CONCLUSION:

In conclusion, the dispute resolution mechanisms outlined in Part XV of UNCLOS present a nuanced and adaptable framework that reflects the complex landscape of maritime disputes. The dual nature of voluntary and compulsory procedures allows states to navigate a spectrum of resolution methods, emphasizing the importance of dialogue and negotiation before resorting to binding third-party settlements. The arbitration procedures under UNCLOS, particularly those established in Annex VII and Annex VIII, serve as pivotal instruments in addressing a wide array of maritime issues. While Annex VII stands as the default and more frequently chosen option, Annex VIII provides a specialized avenue for technical disputes related to the marine environment. The delicate balance between state autonomy and universal compliance is a hallmark of UNCLOS, evident in the flexibility afforded to parties in selecting dispute resolution mechanisms. The Southern Bluefin Tuna Arbitration case underscores the interpretative challenges within the jurisdiction of the Arbitral Tribunal, emphasizing the intricate nature of reconciling different treaty provisions. In essence, UNCLOS not only sets forth a comprehensive regulatory framework but also fosters a dynamic and adaptive environment for resolving disputes at sea. The multifaceted landscape of UNCLOS dispute resolution, shaped by both voluntary and compulsory mechanisms, ensures a fair and balanced approach to maritime conflicts. As states continue to navigate the vast expanse of the world's oceans, UNCLOS remains a cornerstone for fostering cooperation and ensuring the sustainable management of marine resources.

[1] Section 1, Part XV, UNCLOS, Pg. no. 127, see -https://www.un.org/depts/los/convention-agreements/texts/unclos/unclose.pdf

[2] Section 2, Part XV, UNCLOS, Pg. no. 129, see -https://www.un.org/depts/los/convention-agreements/texts

/unclos/unclos_e.pdf

[3] Section 3, Part XV, UNCLOS, Pg. no. 132, see ~https://www.un.org/depts/los/convention-agreements/

texts/unclos/unclos_e.pdf

[4] Art. 298, Section 3, Part XV, Pg. no. 134, see https://www.un.org/depts/los/convention-agreements/

texts/unclos/unclos_e.pdf

[5] Art. 281, Section 1, Part XV, Pg. no. 127, see - https://www.un.org/depts/los/convention-agreements/

texts/unclos/unclos_e.pdf

[6] Art. 282, Section 1, Part XV, Pg. no. 127, see -https://www.un.org/depts/los/convention-agreements/

texts/unclos/unclos_e.pdf

[7] Annex VIII, UNCLOS, Pg. no. 189, see ~https://www.un.org/depts/los/convention-agreements/texts/u

nclos/unclose.pdf

[8] Annex VII, UNCLOS, Pg. no. 186, see ~ https://www.un.org/depts/los/convention-agreements/te

xts/unclos/unclos_e.pdf

[9] Southern Bluefin Tuna Arbitration, Award on Jurisdiction and Admissibility, 4 August 2000, esp. paras. 44-72,

and Separate Opinion of Justice Sir Kenneth Keith, see ~ https://legal.un.org/riaa/cases/volXXIII/1-57.pdf

- UNCLOS dispute resolution unfolds as a dynamic interplay between voluntary and compulsory mechanisms, offering states a tailored approach within its universal framework.

- The complex world of UNCLOS arbitration, featuring Annex VII and Annex VIII tribunals, not only navigates technical intricacies but also underscores the delicate balance between state autonomy and uni

- Delving into the jurisdictional complexities of UNCLOS dispute resolution, 'The Southern Bluefin Tuna Arbitration' unveils the intricate dance between treaty provisions, highlighting the challenges of