Latest News

The UK Approach to Anti-Suit Injunctions in Support of Arbitrations Seated Abroad

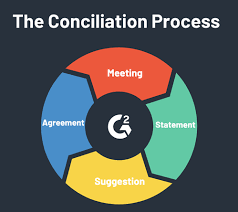

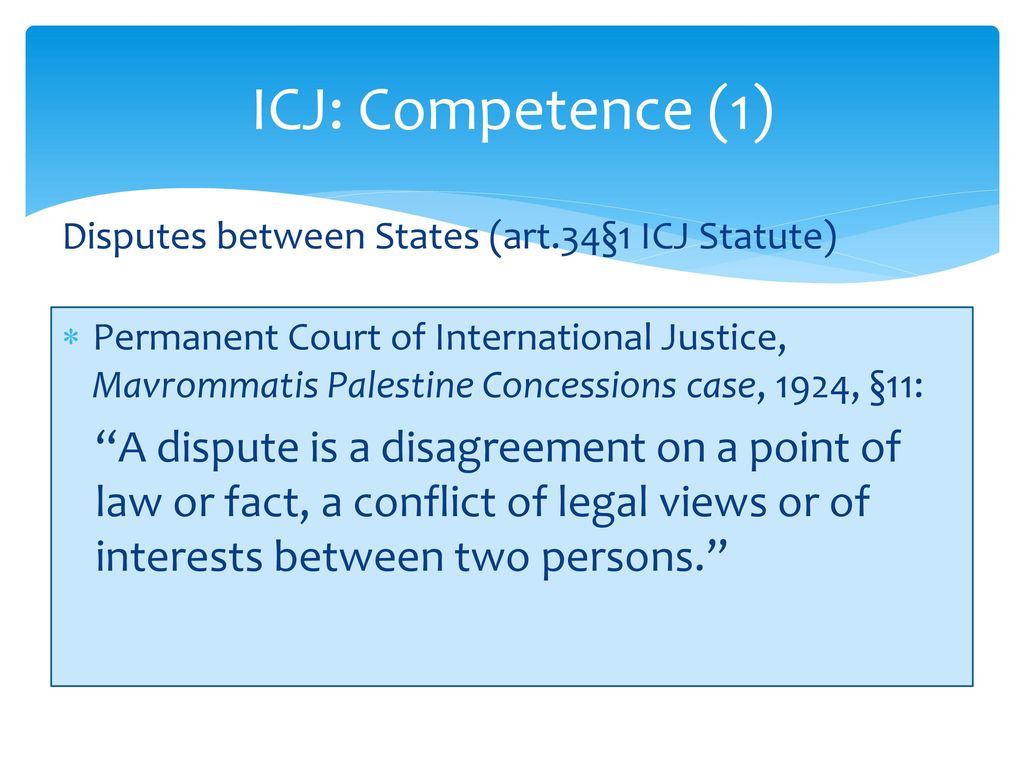

An anti-suit injunction (ASI) is a powerful tool that can be used by a party to an arbitration agreement to restrain another party from initiating or continuing legal proceedings in a foreign court that is in breach of the arbitration agreement. However, the availability and scope of this remedy may depend on the law of the seat of arbitration, which is the legal system that governs the procedural aspects of the arbitration. In this blog post, we will examine the recent case law and legal principles that apply when a party seeks an ASI from an English court in support of a foreign-seated arbitration.

The Legal Basis and Rationale for ASIs

The English courts have a long-standing practice of granting ASIs to protect the integrity and effectiveness of arbitration agreements and to prevent parties from circumventing or undermining the arbitral process. The legal basis for this remedy is derived from section 37(1) of the Senior Courts Act 1981, which gives the High Court a general power to grant an injunction in all cases where it appears to be just and convenient. This power is not limited by the Arbitration Act 1996, which does not expressly address ASIs but supplements it by providing additional powers for the court to support arbitration under section 44.

The rationale for granting ASIs is based on two main considerations: (i) the contractual obligation of the parties to honour their agreement to arbitrate; and (ii) the comity or respect for foreign courts. The first consideration reflects the principle that parties should be held to their bargain and should not be allowed to escape or delay their contractual obligations by resorting to foreign litigation. The second consideration recognises that ASIs are an interference with the sovereignty and jurisdiction of foreign courts, and therefore should be exercised with caution and restraint, taking into account the interests of justice and international relations.

The Conditions and Factors for Granting ASIs

The English courts have developed a set of conditions and factors that guide their discretion in granting ASIs in support of arbitration. These include:

- The existence of a valid arbitration agreement that covers the dispute in question. The court must be satisfied that there is a high degree of probability that the parties have agreed to arbitrate their dispute and that the foreign proceedings are in breach of that agreement. The court may apply a summary judgment or strike-out test to determine this issue, without conducting a full trial on the merits.

- The absence of exceptional circumstances that justify or excuse the breach of the arbitration agreement. The court must consider whether there are any reasons why it would be unjust or inequitable to grant an ASI, such as delay, waiver, estoppel, acquiescence, forum conveniens, or public policy. The burden is on the party seeking to avoid the arbitration agreement to show such exceptional circumstances.

- The balance of convenience and justice between the parties and the foreign court. The court must weigh up the potential harm and prejudice that may be caused to each party by granting or refusing an ASI, as well as the impact on the foreign court and its proceedings. The court must also take into account any relevant factors such as the stage and status of the foreign proceedings, the availability and effectiveness of alternative remedies, the risk of inconsistent or conflicting decisions, and the attitude and approach of

the foreign court towards arbitration.

The Application and Limitations of ASIs in Support of Foreign-Seated Arbitrations

While the English courts have frequently granted ASIs in support of arbitrations seated in England, they have been more reluctant and careful when it comes to arbitrations seated abroad. This is because some additional complications and challenges arise when dealing with foreign-seated arbitrations, such as:

- The jurisdictional basis and scope for granting ASIs. The court must have a sufficient connection or nexus with the parties or the subject matter of the dispute to justify its intervention in foreign proceedings. This may depend on whether the parties are domiciled or present in England, whether English law governs the arbitration agreement or the substantive contract, whether there is an exclusive jurisdiction clause in favour of England, or whether there is any other ground for service out of jurisdiction under CPR 6.36/PD6B.

- The deference and respect for the law of the seat and its courts. The court must consider whether granting an ASI would be consistent or compatible with the law of the seat, which is normally chosen by the parties as part of their arbitration agreement. The court must also consider whether granting an ASI would be respectful or offensive to the courts of the seat, which have primary supervisory authority over the arbitration. The court must avoid any conflict or clash with the law or the courts of the seat that may undermine the arbitration or the enforcement of the award.

These issues have been illustrated by several recent decisions of the English courts, which have reached divergent outcomes and opinions on whether to grant ASIs in support of foreign-seated arbitrations. We will summarise four of these decisions below and analyse the principled bases of their reasoning.

SQD v QYP [2023] EWHC 2145 (Comm)

In this case, the parties agreed to an overseas project, which was governed by English law and provided for ICC arbitration seated in Paris. A dispute arose between them and QYP commenced court proceedings in Russia, alleging that the arbitration agreement was unenforceable because it would not have access to justice in an ICC arbitration in Paris. SQD responded by commencing ICC arbitration in Paris and applying to the English court for an interim ASI to restrain QYP from pursuing the Russian proceedings.

Bright J refused to grant the ASI, on the basis that it would conflict or clash with the law and the courts of France, which was the chosen seat of arbitration. He relied on the evidence that French law had a philosophical objection to ASIs and would not grant them for reasons of public policy and that French courts would not recognise or enforce ASIs issued by foreign courts. He also reasoned that the parties had selected Paris as the seat knowing that French law and courts would not grant ASIs, and therefore their objective intention was to exclude such a remedy. He distinguished this case from previous cases where ASIs were granted in support of foreign-seated arbitrations, such as Ust-Kamenogorsk and Ecobank, on the basis that there was no evidence of any conflict or clash with the law or the courts of the seat in those cases.

Deutsche Bank AG v RusChemAlliance LLC [2023] EWCA 1144

This case involved the same parties and facts as SQD but with a different outcome. SQD appealed against Bright J's decision to the Court of Appeal, which allowed the appeal and granted the ASI. The Court of Appeal did not disagree with Bright J's reasoning or approach, but rather based its decision on fresh evidence that showed that French law and courts did not have a principled objection to ASIs being sought or granted by foreign courts, notwithstanding that they would not grant them themselves. This evidence removed the perceived conflict or clash that justified Bright J's original decision.

The Court of Appeal also noted that Bright J had not considered whether any exceptional circumstances militated against granting an ASI, such as forum conveniens or public policy, and remitted this issue to be determined by him at a further hearing.

Enka Insaat Ve Sanayi AS v OOO Insurance Company Chubb [2023] EWHC 2230 (Comm)

In this case, the parties entered into a contract for the construction of a power plant in Russia, which contained an arbitration clause providing for ICC arbitration with no express choice of seat. A fire broke out at the plant and Chubb, as the insurer and subrogee of the owner of the plant, commenced court proceedings in Russia against Enka and others, seeking damages for the fire. Enka applied to the English court for an interim ASI to restrain Chubb from pursuing the Russian proceedings. Robin Knowles J granted the ASI, pending a contested final hearing, on the basis that there was a high degree of probability that the parties had agreed to arbitrate their dispute and that there were no exceptional circumstances that justified Chubb's breach of the arbitration agreement. He distinguished this case from SQD on two grounds: (i) there was no evidence that Russian law or courts had a philosophical objection to ASIs or would not recognise or enforce them, and (ii) there was no evidence that the parties had chosen a foreign seat of arbitration that would preclude the availability of ASIs. He also noted that Enka had commenced ICC arbitration in London as the seat is provisionally determined by the ICC Court under its rules.

Republic of Djibouti v Boreh [2023] EWHC 2911 (Comm)

In this case, the parties entered into various agreements relating to port facilities in Djibouti, which were governed by Djiboutian law and contained arbitration clauses providing for LCIA arbitration seated in London. A dispute arose between them and Djibouti commenced court proceedings in Djibouti and Dubai against Boreh and others, alleging fraud and corruption. Boreh applied to the English court for a final ASI to restrain Djibouti from pursuing foreign proceedings.

Flaux J granted a final ASI to restrain court proceedings commenced in Dubai in breach of an arbitration agreement providing for LCIA arbitration seated in London. The judge held that granting an ASI was appropriate to enforce the party's bargain to arbitrate and that there was no evidence that Dubai courts would object to such relief.

Conclusion

The above cases demonstrate that obtaining an ASI from the English courts in support of foreign-seated arbitrations is not a straightforward or predictable process. The outcome will depend on various factors, such as:

- The law governing the arbitration agreement and its interpretation;

- The law and policy of the seat and the forum of the foreign proceedings;

- The evidence of foreign law and its impact on the court's discretion;

- The parties' choice of seat and curial law and its implications;

- The interests of justice and the balance of convenience.

Therefore, parties seeking or resisting an ASI in such cases should be prepared to address these issues and provide relevant evidence and arguments to persuade the court to exercise its discretion in their favour.

- English courts can grant anti-suit injunctions under section 37(1) of the Senior Courts Act 1981, but must respect section 2(3) and section 44 of the Arbitration Act 1996.

- Anti-suit injunctions are effective and appropriate, but require caution and comity, especially for foreign courts or tribunals.

- The role of the seat in anti-suit injunctions is not settled and may vary depending on the facts and arguments of each case.