Latest News

Speedy Redressal Mechanism for Arbitration in India

Arbitration is an ancient practice in India that has been revived in recent years as an alternative dispute resolution (ADR) method. Arbitration can offer several advantages over litigation, such as speed, flexibility, confidentiality, and cost-effectiveness. However, arbitration also faces some challenges and limitations in India, such as delays, high fees, a lack of quality arbitrators, and judicial interference. This blog post will discuss some of the recent developments and key challenges in the field of arbitration in India and suggest some ways to improve the speedy redressal mechanism for arbitration.

Recent Developments

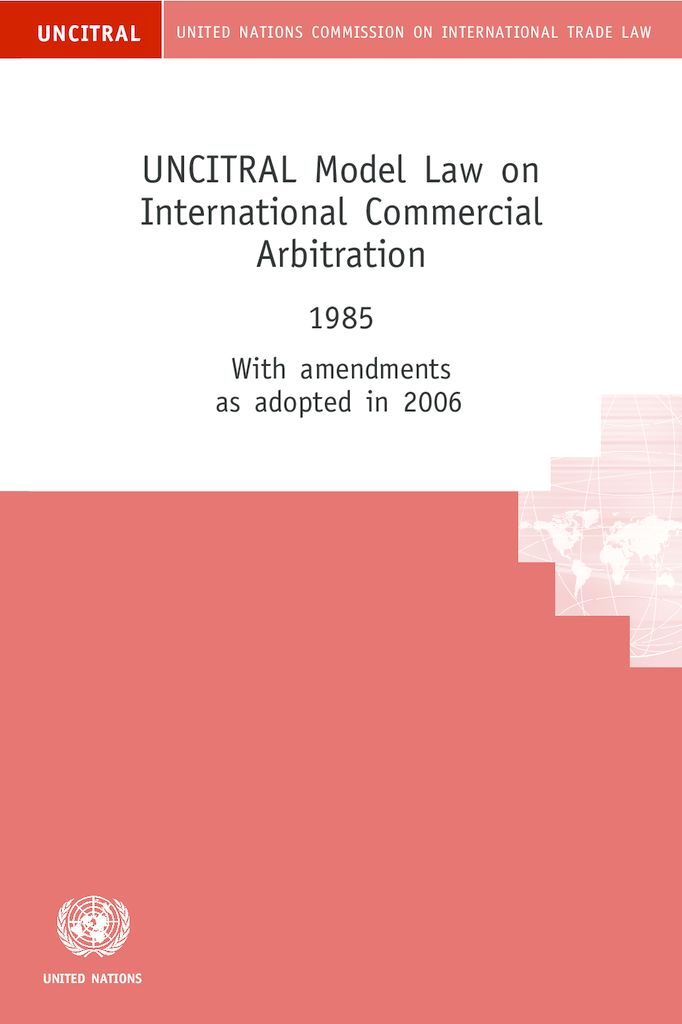

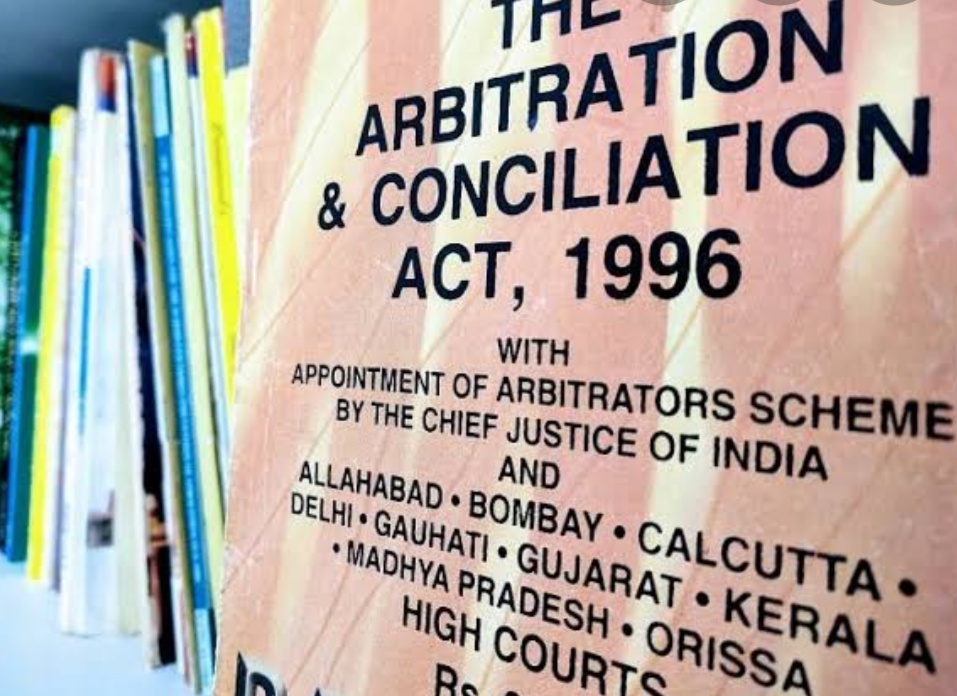

The Arbitration and Conciliation Act, 1996 (the Act) is the main legislation that governs arbitration in India. The Act is based on the UNCITRAL Model Law on International Commercial Arbitration, 1985, and aims to provide a comprehensive and uniform framework for domestic and international arbitration in India. The Act has been amended twice, in 2015 and 2019, to address some of the issues and shortcomings of the original Act and to make arbitration more efficient and effective in India. Some of the notable features of the amendments are:

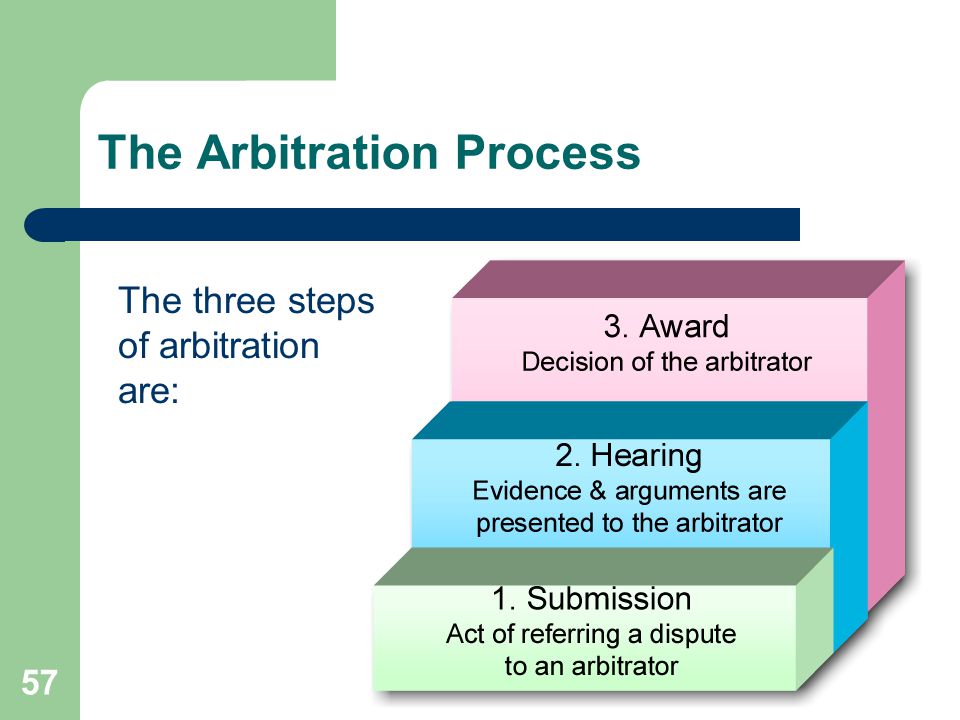

Time limit for arbitration: The 2015 amendment introduced a time limit of 12 months for the completion of arbitration proceedings, extendable by another six months with the consent of the parties, and further extendable by the court only on sufficient cause and on such terms and conditions as it may deem fit. This provision was aimed at reducing delays and ensuring the speedy disposal of arbitration cases.[1]

Fast-track procedure for arbitration: The 2019 amendment introduced a fast-track procedure for arbitration cases where the value of the dispute does not exceed INR 3 crore (approximately USD 400,000). This expedited process aims to resolve disputes within six months.[2]

Appointment of arbitrators: The 2015 amendment changed the procedure for the appointment of arbitrators by giving more autonomy to the parties and reducing the role of courts. The amendment also prescribed certain qualifications, experience, and accreditation for arbitrators. The 2019 amendment established an independent body called the Arbitration Council of India (ACI) to promote and regulate arbitration in India. The ACI is responsible for grading arbitral institutions, accrediting arbitrators, maintaining a depository of arbitral awards, and framing policies and guidelines for arbitration.[3]

Interim relief: The 2015 amendment clarified that an arbitral tribunal has the same power as a court to grant interim relief during or before the commencement of arbitration proceedings. The amendment also made it easier for parties to seek interim relief from courts in cases of international commercial arbitration where the seat of arbitration is outside India.[4]

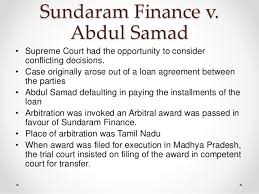

Enforcement of awards: The 2015 amendment made it more difficult for courts to set aside arbitral awards on grounds of public policy or patent illegality. The amendment also clarified that an award would not be automatically stayed by setting aside the award unless the court grants a stay on a separate application made for that purpose. The 2019 amendment further provided that a stay on enforcement of an award can only be granted by a court if it is satisfied that a prima facie case is made out that the award is against justice or morality or in contravention of the fundamental policy of Indian law.[5]

Key Challenges

Despite these amendments, arbitration in India still faces some challenges and limitations that affect its speedy redressal mechanism. Some of these are:

High costs: Arbitration can be expensive in India due to various factors such as high fees charged by arbitrators and arbitral institutions, multiple hearings, extensive documentation, stamp duty on awards, legal fees, etc. These costs can deter parties from opting for arbitration or pursuing their claims effectively.[6]

Lack of quality arbitrators: There is a shortage of qualified, experienced, and impartial arbitrators in India who can handle complex and diverse disputes. Many arbitrators are retired judges or lawyers who may not have adequate knowledge or expertise in specific fields or sectors. There is also a lack of diversity among arbitrators in terms of gender, age, nationality, etc.[7]

Judicial interference: Although the amendments have tried to minimize judicial intervention in arbitration matters, there are still instances where courts interfere with or delay arbitration proceedings or the enforcement of awards. For example, courts may take a long time to appoint arbitrators, grant interim relief, or stay orders. The courts may also adopt a narrow or expansive interpretation of certain provisions of the Act or exercise their inherent powers to review arbitral awards on grounds not specified in the Act.[8]

Suggestions for Improvement

To improve the speedy redressal mechanism for arbitration in India, some of the possible suggestions are:

Creating a pool of trained and accredited arbitrators: There is a need to create a pool of trained and accredited arbitrators who can handle various types of disputes efficiently and effectively. The ACI can play a vital role by developing and implementing standards and criteria for accreditation, training, and evaluation of arbitrators. The ACI can also maintain a roster of arbitrators and facilitate their appointment through arbitral institutions or online platforms.[9]

Promoting institutional arbitration: There is a need to promote institutional arbitration over ad hoc arbitration in India. Institutional arbitration can offer several benefits, such as fixed rules and procedures, administrative support, quality control, transparency, and accountability. The ACI can grade and recognise arbitral institutions based on their performance and quality of services. The government can also encourage or mandate institutional arbitration for certain types of disputes, such as public contracts, infrastructure projects, etc.[10]

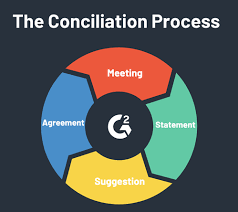

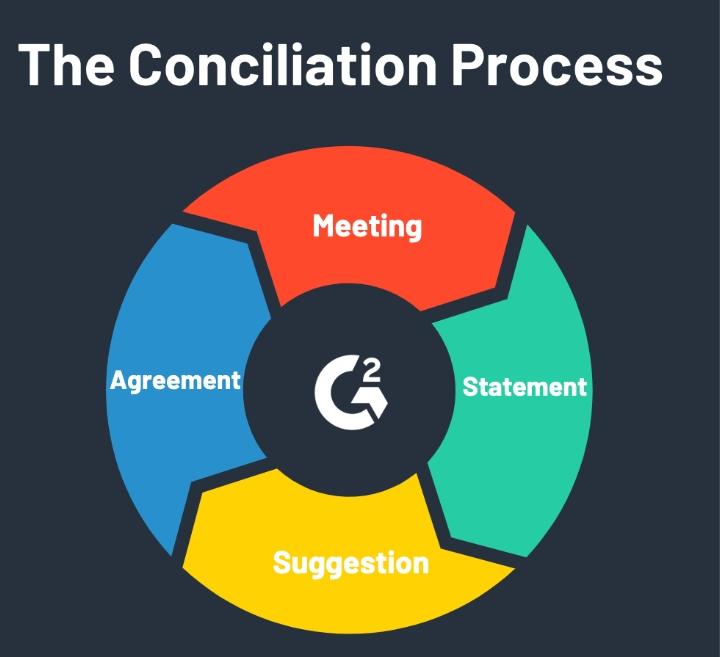

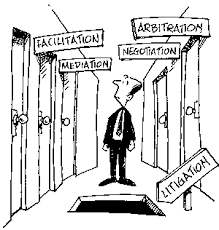

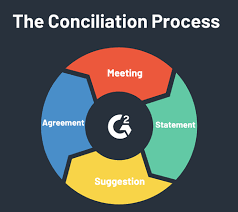

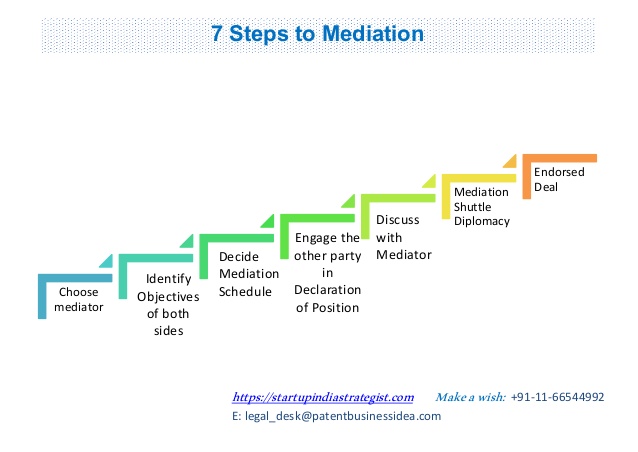

Encouraging alternative modes of dispute resolution: There is a need to encourage alternative modes of dispute resolution (ADR) such as mediation, conciliation, negotiation, etc. that can help parties resolve their disputes amicably and expeditiously. ADR can also reduce the burden on courts and arbitrators and save costs and time for the parties. The Act provides for the possibility of settlement through mediation or conciliation during arbitration proceedings. The courts can also refer parties to ADR under Section 89 of the Code of Civil Procedure, 1908.

Conclusion

Arbitration is an important and effective mode of dispute resolution in India that can offer speedy redress to the parties. However, arbitration also faces some challenges and limitations that need to be addressed and overcome. The amendments to the Act have brought some positive changes and reforms in the field of arbitration in India, but there is still scope for improvement and innovation. The government, the judiciary, the ACI, the arbitral institutions, the arbitrators, the lawyers, and the parties all have a role to play in making arbitration more efficient and effective in India.

References

[1] Section 29A of the Arbitration and Conciliation Act, 1996 (as amended in 2015).

[2] Section 29B of the Arbitration and Conciliation Act, 1996 (as amended in 2019).

[3] Section 11 of the Arbitration and Conciliation Act, 1996 (as amended in 2015).

[4] Sections 43A to 43M of the Arbitration and Conciliation Act, 1996 (as amended in 2019).

[5]Section 17 and Section 9(2) of the Arbitration and Conciliation Act, 1996 (as amended in 2015).

[6] Section 34(2A) and Section 36(2) of the Arbitration and Conciliation Act, 1996 (as amended in 2015).

[7] Section 36(3) of the Arbitration and Conciliation Act, 1996 (as amended in 2019).

[8] See Anirudh Krishnan & Rishabh Raheja, 'The Cost Conundrum: Why is Arbitration Expensive in India?', Indian Journal of Arbitration Law, Vol. VII Issue I (2018), available at https://ijal.in/sites/default/files/IJAL%20Volume%207_Issue%201_Anirudh%20Krishnan%20&%20Rishabh%20Raheja.pdf.

[9] See Anuroop Omkar & Kshama Loya Modani, 'Arbitrator Diversity: A Distant Dream?', Nani Palkhivala Arbitration Centre Newsletter (2020), available at https://nparbitration.in/wp-content/uploads/2020/04/NPAC-Newsletter-April-2020.pdf.

[10] See Shashank Garg & Shreya Gupta, 'Judicial Intervention in Arbitration Proceedings: A Necessary Evil?', SCC Online Blog (2020), available at https://www.scconline.com/blog/post/2020/06/30/judicial-intervention-in-arbitration-proceedings-a-necessary-evil/.

- Fast-track procedure is for small disputes that can end in six months. The parties can pick or request this procedure, which lets the tribunal decide based on papers and documents with no formalities.

- You can use emergency arbitration for urgent interim relief. It can help you if you can lose a lot without interim relief. It is not in Indian law, but it is in some arbitration rules in India.

- Institutional arbitration has guidance, quality check, help, fairness and trust. It can be better than ad hoc arbitration.