Latest News

Conciliation and Militancy in the Israeli-Palestinian Conflict

Conciliation and Militancy in the Israeli-Palestinian Conflict

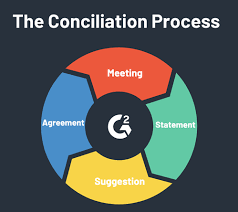

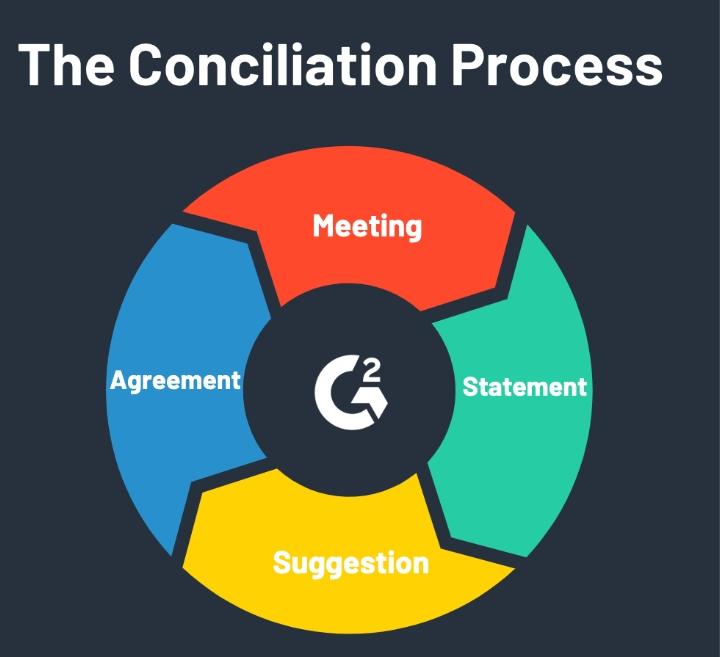

The model suggests that terrorist organizations become more militant after concessions, as only moderate terrorists accept them, leaving extremists in control. Because former terrorists work together to strengthen counterterrorism skills, governments are more ready to compromise. The model also produces hypotheses about the amount of money that governments should spend on counterterrorism, the conditions under which moderate terrorists agree to give in, the length of time that terrorist conflicts last, the incentives that moderate terrorists have to radicalize their followers, and the incentives that governments have to support radical challenges to moderate terrorist leaders. An application of the paradigm to the Israeli-Palestinian conflict is shown. The commitment issue that arises when giving in to armed rebels is also covered in the essay, with the suggestion that terrorists could not trust the government to keep its word.

Terrorists receive concessions from the government, some of which are public commodities and others of private goods. Through counterterrorism, the government hopes to destroy the terror group; the likelihood of success determines how much it will cost. The amount of money spent on counterterrorism and the extent to which ex-terrorists are assisting the government decide how successful the government is. If the government beats the terrorists, it will earn a payout of W; if it is beaten, it will receive a payout of 0 forever. Every round that the terrorists fail to beat it in earns the government further benefits. Taking into account concessions, attempted terror, and prior terrorist support, the government determines the appropriate amount of counterterrorism to maximize its projected benefit. When confronted with a more violent adversary, the government invests more in counterterrorism; conversely, it uses former terrorists' assistance more effectively.

The inclinations of the surviving active groups dictate the degree of violence inside a terrorist organization. The true preference of a faction is ascertained by maximizing its predicted usefulness. The likelihood that the terrorists will be defeated rises with the extent of counterterrorism that the government does. A terror group made up entirely of extremists commits more terror than one made up of both moderates and extremists if both are equally well-financed, provided that resources do not decrease following concessions. Nonetheless, if the terrorists' access to resources declines significantly after concessions, the group's enhanced militancy may be more than offset by the reduction in resources. Because the radicals won't have the resources to employ as much violence as they would like, there will be less bloodshed in this situation even if militancy is higher.

The amount of violence committed by terrorist groups both with and without concessions. It finds that, as long as there is not a significant loss of resources, terrorist groups continue to carry out more atrocities. Concessions from governments come with a price since ex-terrorists support counterterrorism initiatives to guarantee the legitimacy of the concessions and boost funding for counterterrorism. The concept also explains why governments are occasionally prepared to give in since they boost their expenditure on counterterrorism and receive assistance from ex-terrorists. This means that while still actively committing acts of terror, moderate terrorists may show that they can manage radicals among their ranks, but they may be reluctant to destroy them after they make compromises. Using a model that implies government concessions to moderate terrorists might result in increasing violence, the paper analyses the Israeli-Palestinian conflict. According to the model, Israel underestimated the Palestinians' ability to combat terrorism, which resulted in less aid being provided. However, the government's actions afterwards suggest that Israeli policymakers misjudged the terrorist movement's intensity. It is anticipated that the longer-lasting and movement-specific makeup of the greater militancy impact would result in a sustained upsurge in terrorist activity.

The author contends that there are other factors contributing to the violence in the Israeli-Palestinian conflict than the spoiler effect, which happens before significant accords. Rather, it implies that other elements, such as heightened militancy from organizations like Islamic Jihad and Hamas, could also be involved in the rise in violence. The author classifies the elections in Israel and Palestine as spoiler opportunities, which have produced disparate results. Along with this, the author points out that from the start of the second Intifada, there has been a qualitative rise in violence, but this was not the case before Oslo II, the Israeli elections, the Wye Accords, the Sharm el-Sheik Memorandum, or the Camp David discussions. To ascertain if the spoiler effect accounts for the majority of the rise in violence following Oslo before the second Intifada, the author proposes doing more research.

The study, which focuses on the time frame from September 1993 to September 2000, investigates how concessions made by the government affect terrorist groups. The findings indicate that there is a slightly greater degree of violence when there are spoiler chances, but the difference is not statistically significant. There have been more violent incidents after the Oslo Accord was signed, for reasons other than the spoiler effect, such as heightened militancy. The analysis also reveals that the rise in violence followed the moderates' compromises, giving radicals control of the terrorist movement. The Palestinians utilized Israeli pledges to ensure their legitimacy, and in exchange, Israel made concessions only if they received help in combating terrorism. The research indicates that governments may be able to resolve the issue of credible commitment when making concessions by enabling ex-terrorists to assist in counterterrorism.

- While concessions can lead to heightened militancy, significant reductions in terrorist resources post-concessions may offset this, resulting in an overall decrease in violence.

- Governments, leveraging ex-terrorist support, increase counterterrorism funding and efforts when faced with more violent adversaries, aiming to maximize their projected benefit.

- Terrorist organizations tend to become more militant after concessions, as moderates accept the concessions, leaving extremists in control.